The Technician And His Problems

It has been appropriately said that the film technician whether he be behind the camera, or the console of the sound mixer, has so far never let down the writer, the director or the artistes in the making of the motion picture. In other words, technical advances have invariably kept ahead of the so-called creative arts. That , of course, was only to be expected, for mostly all writers, directors, and especially artistes, just drifted into the Industry without any previous specialised training in the arts relative to medium of the motion picture as such. For instance, an eminent writer of short stories or the novel, or even a poet, who entered films and ultimately became a script writer of repute, never at any time actually studied "script writing". His knowledge has always been based mainly on experience. Such a state of affairs for the cameraman or sound engineer is unthinkable. Who for example, would entrust his million rupee production into the hands of even the most creative camera pictorialist, whose picture may have adorned the best photographic salons of the world? No, he and his counterpart, the Second Engineer must needs have studied perhaps for years his art, especially related to the motion picture. In the absence of a regular training Institute, this knowledge has necessarily had to be gained by working with and watching the accepted masters of their profession. But these very masters themselves, have been trained the hard way with little or no theoretical background and what is still more important, little knowledge to others.

However, the system has worked so far, because as I have said before, technology in films is still ahead of every other field. It might even continue to work. So then, what exactly is the problem.

The problem is this, that technological advances are today moving much too fast for the Indian technician to keep pace in the old traditional manner of learning at the feet of the guru. He must, if he is to survive, go about his business in a far more serious way than to what he has been accustomed.

That naturally leads us to the recent establishment of the Film Institute, and the part that it has to play in the training of the future technician.

I said, "future", but what of the existing technician? Here too, the Institute has provided refresher classes for everybody. So there is little more to be done. Everything appears quite rosy. Any problems that existed have been solved.

But have they been solved? Unfortunately at the back of every problem, there is always an economic brake to prevent an easy solution. In the formation of the Institute, as in everything else, we have been more impetuous rather than realistic. Planning, that was so necessary before the Institute was formed, was left to be carried out after the Institute was in full swing- with or without pupils.

We have admitted that the technician, even if he is at top of his profession needs refresher classes, or his knowledge will soon be of the past.

But take him away from his present position, throw him at an Institute for six months, and when you bring him back he will have lost his job and will probably find his erstwhile assistant safely perched on his seat behind the camera.

Take again the case of the assistant who joins the Institute in the hope of acquiring knowledge a little quicker, he comes back six months or a year later full of ideas but empty of pocket-because in the meanwhile the second assistant has been promoted and he has lost his place. He runs around the producers in the hope of finding someone who will give him independent work, but having neither experience, nor any relatives of the producer to put in a good word for him, he is merely shunted from door to door.

To come from generalisation to specific cases, I would like to know if there has been a single case of a trained diploma holder from either the Bangalore, or the Madras Institute who has been able to secure an independent assignment with a producer. No one, and least of all myself, who is familiar with the teaching at these Institutes, will say that their standard is inadequate. Why then should such a state of affair exist? The answer is not far to seek. It is the peculiar conditions of Indian Film Industry, where the moghuls that constitute its hierarchy have created a "hands off" world of their own.

Even the Films Division, for after all it once drew its top executives from the Film Industry, is not immune. Or else why have they not thought a graduate from any of the two Institutes I have mentioned, as fit for an independent charge?

But the Films Division is a state enterprise. It may blunder and make mistakes. Those that so blundered and made mistakes will gradually give way to others less susceptible to blundering and making mistakes till one day we may find them much closer to the ideal which we can hope for in an Industry where at present, but for a few isolated cases, the worker is considered merely a cog in a gigantic machine that makes money faster than the owners can spend it.

I have been referring to film production as an industry, but I am afraid that if it is an Industry it is a queer one, where there is no security or no regular wage-scale for the employees. You will find on the one band employees drawing six to seven lakhs of rupees for a picture and paying income tax on just 1/12th of the amount, while on the other side there are workers drawing one hundred rupees a month and paying tax on five times the amount. One wonders if anyone in films ever heard of Avadi as the place where the Indian National Congress passed its pious regulation declaring its goal of establishing a socialistic pattern of society. I have known many a producer who has had a few flops at the box-office and has declared in consequence his inability to pay his staff even money for them to buy their rations with, while he continues to run around in the petrol-consuming Chevrolet. I know also another, who actually evaded his creditors by becoming insolvent, and yet I never found him standing in a queue with me at the bus stop. His Dodge, or was it Plymouth, still continues to run as merrily as ever between his house and the houses of such top artistes on whose strength the hopes to obtain money for his next.

Also, we must remember that if the Cine-Technician is to improve his lot he must do so along with the other crafts that go towards the making of the film.

The Federation of Western India Cine Employees has undoubtedly realised this most important aspect and are determined to put up a united front against the forces of reaction that threaten the entire Industry.

My own association with the Federation has been since its very inception and I am proud of it. Nevertheless, I feel that all our efforts so far have been merely to seek and secure remedies for the ills as they come along. In this, we have gained a good measure of success. But, a time has come, or at least is just around the corner, when I personally feel that we must decide to strike a blow for the complete eradication of the cancer that threatens to swallow the entire Industry.

To my mind, there is only one remedy and that is complete nationalisation. There will be disruption, there will be chaos, but after the smoke has subsided, there will rise like a phoenix from the ashes a new and cleaner Industry of which any cine-technician can really be proud.

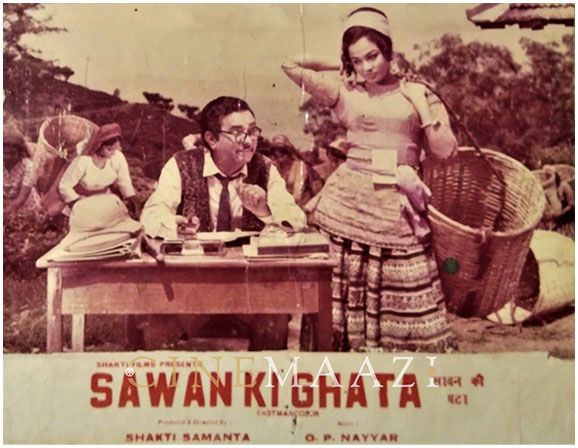

This article was written by Krishna Gopal and was originally published in Film Industry of India, compilled by B K Adarsh in 1963. The images used in the feature were not part of the original article and is taken from Cinemaazi archive.

About the Author

.jpg)