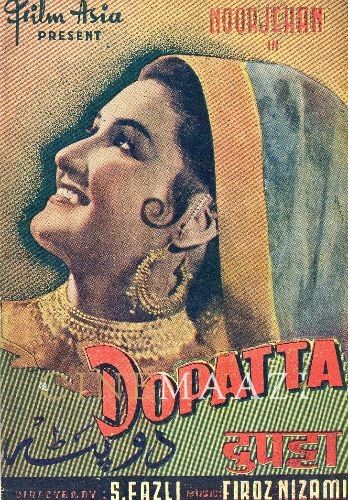

The Case of Emotional Turmoil In Dopatta (1952)

Film Asia’s Dopatta (1952) is the first quality film we have seen from Pakistan. In lavish production values, technical excellence and the deft direction it equals anything from the home or foreign market to have yet reached the Indian screen. But the claims of Dopatta at the box-office do not rest on the above-mentioned trinity of virtues alone. Its musical score is easily the best to have come from the sound-track in recent years.

Noorjehan, erstwhile nightingale of the Indian screen, stages a grand comeback after five years. Her lilting melodies provide a most delightful thrill. But music alone cannot guarantee success to a film. The lyrics of Nirala (1950) and Shinshinaki Booblaboo (1952) are still popular although both films have been prize flops. A good film must of necessity have a well-knit screenplay, dexterously presented. Dopatta has these attributes too.

Its love theme poses a pertinent question: “Does a woman love a man for his good looks or for his soul?” The story that plays upon this theme flickers around a girl who defies a hill-tribe to marry a handsome army officer. The fruit of their love is a beautiful child. The husband is sent to the front and is reported missing. After a lapse of many months, during which the heroine undergoes tragedy and heartbreak, the husband returns—disfigured, mutilated, unpresentable. No one is able to recognize him.

In sheer desperation, he wants to kill his wife. In these scenes, the director has wielded the megaphone with skill and power. Each time the husband raises his revolver, the child unknowingly comes before his mother; the situation alters. Gradually a change comes over the man. He wants to get away from his wife so that her happiness may not be marred. The drama of conflicts moves from action to action.

Even when he is revealed to his wife and she clings to him with devotion, the suspense does not end.

The craftsmanship of the photographer and fast editing has added to the tempo of the film. But often in anxiety to march ahead of his theme, the director has left many things unexplained, leaving one to infer and guess. Because of this drawback, many situations are confusing.

The acting as a whole is most satisfactory. Noorjehan is the body and soul of the film. She gives a convincing performance and has lost little of her former glamour though the years have marched inexorably on. Veterans Ghulam Mohammad and Bibbo display the talents they are still remembered for. Sudhir, the handsome doctor in the film, has revealed himself as an actor of great promise. Ajay Kumar, who is nobody’s oil-painting, is far indeed from the handsome husband. Even his acting is lackadaisical enough to cast a blemish upon so realistic a production.

Despite these defects, Dopatta is a gripping and melodious film and it tells in no uncertain terms what the Pakistan industry is capable of doing. It is a challenge and a very serious warning to Indian producers.

Cinemaazi thanks Sudarshan Talwar and Cineplot for contributing this review.

About the Author

.jpg)