Should a Filmmaker be Original?

It is a demonstrable fact that a great majority of films are based on existing stories. There is nothing repugnant in this. In fact, it has two obviously admirable aspects: the writers of the stories are provided with an additional (and often unexpected) source of Income, the directors have a ready-made base to start from.

Need the director, as a conscientious artist, be reluctant to use another's idea? No, indeed, for he is in good company. Shakespeare and Kalidasa have done it in literature. Most great operas and ballets have been based on existing Ideas.

With the possible exception of Chaplin, who is obliged to build his plots around his own unique personality (even he, too, once used a borrowed idea in "Monsieur Verdoux"), all great film makers have fashioned classics out of other people's stories.

Well, one may just as well ask: What did Shakespeare contribute in "Hamlet," or Kalidasa in "Shakuntala"? Or, what was the con¬ trib11tion of the Vaishnava poets, who had only one basic situation to write their verses on¬ Krishna's love for Radha?

Reduce the plot of "Anna Karenina" to its essentials, and what are we left with? The staple story-line of a thousand cheap novelettes.

And yet what is it that makes a master piece of "Anna Karenina"?

which is the third part of the trilogy.

Before one answers these questions, let us go back a little further and see what guides the film maker in his choice of a story.

If the film maker wants primarily to make money (a perfectly legitimate propensity), it is likely that he will turn to a best-seller.

But few such slavish translations have ever made worthwhile films, and the degree to which an audience accepts such films determines the degree to which it is unaware of the purpose and scope of the true film adaptation.

If they were, they would read like scenarios; and, if they were good scenarios, they would probably read badly as literature, for scenarios are no more than indications in words of what is really meant to be conveyed in images.

When I say 're-shaping', I do not mean re¬ shaping beyond recognition. Obviously there are elements which remain unaltered or at least are recognisable.

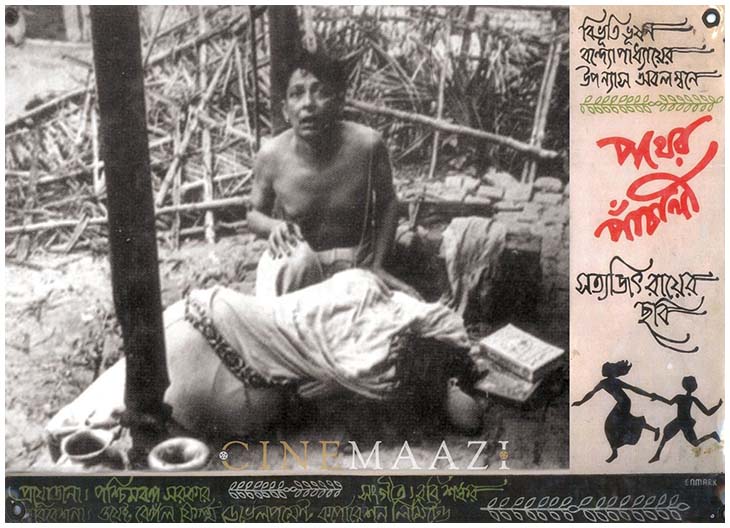

I have made a trilogy of films based on two well-known Bengali novels. The first part of the trilogy, "Pather Panchali," was based on the book which bears the same name. It is a great book, a classic of Bengali literature with many qualities, visual as well as emotional, which are transcribable on film.

I tried to retain these qualities in the film.

The second part, "Aparajito," deals with the adolescence of the central character Apu, and is based on the last portion of the book, "Pather .Panchali," and the first portion of the second novel, which is also called "Aparajito."

As a novel, "Aparajito" is far below "Pather Panchali." It is long-winded and diffuse, it has too many characters and it often gets bogged down in a kind of humdrum naturalism. But the first half of it has at least one notable aspect - the profound truth of the relationship between the widowed mother and the son who grows away from her.

The whole raison d'etre of the scenario, as, indeed, of the film, was this particular poignant conflict.

The third part of the trilogy, "Apur Sansar," which is based on the second half of the novel "Aparajito," presented more problems. The orphan Apu was now a young man and, as depicted by the author Bibhutibhusan, he charts a somewhat unclear emotional pattern.

Apu, just out of college, goes about hunting for a job, but is really more inclined to¬ wards creative pursuits. He is enamoured of one girl, but is forced to marry another.

This does not produce the expected emotional crisis because Apu grows to love his wife, this requiring no conscious effort on his part. The author makes no attempt to inter¬ weave these two relationships.

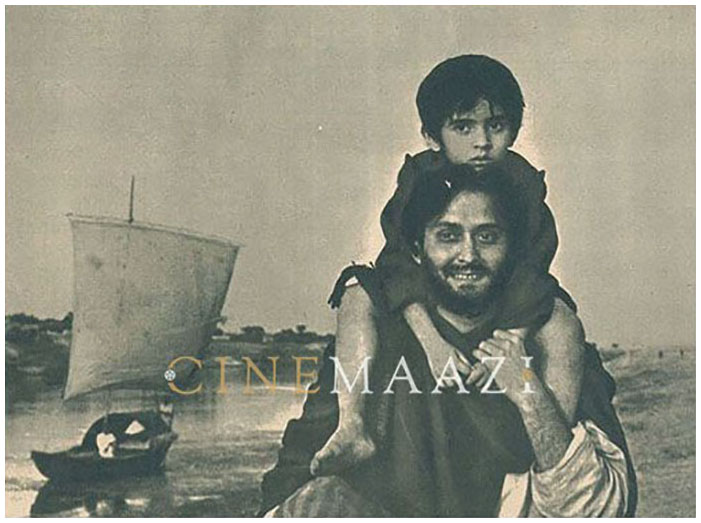

The wife dies in childbirth. Apu is too upset to enquire about the baby which has survived. He forsakes the child, leaves the city, and lands a job in a mofussil town. He tires of this job in a few years' time and has an urge to see his long-neglected son.

The meeting is brief, whereupon Apu leaves the boy again, goes off to the forests of Nagpur to find peace and a job, again comes back to his son, is overwhelmed by sudden paternal affection and decides to settle down in the city with the boy.

There is a last meeting with the first girl, when she is about to commit suicide. Apu writes a novel, earns some acclaim and, to round it off, he leaves the boy, now eight years old, in the care of friends and sets out on a vague mystical quest for peace in some unnamed region.

It is true that, in the relaxed span of the four hundred pages of the book, the events do not seem as absurdly juxtaposed as they do in my resume. But it is clear that a film of average length has no room for even a third of this material.

As a matter of fact, concentrated mainly on two aspects. One was the relationship between the struggling intellectual Apu and his unaffected, unlettered chance-wife Aparna, brought up in affluence but inspired to adjustment with poverty by her love for her husband.

The second aspect was even more exciting. Aparna dies in child-birth. A conventional writer would have made the father rush to the crib of the surviving child.

Bibhutibhusan, who often reached for the truth below the surface, makes Apu turn against the child - he reproaches him for having caused the mother's death.

The first meeting of father and son takes place after a lapse of several years. A scenarist could scarcely want more in the way of an expressive situation.

"Apur Sansar" thus grows out of situations conceived by the author himself. I, as the interpreter through the film medium, exercised my right to select, modify and arrange.

This is a right which every film maker, who aspires to more than doing a commercial chore - to artistic endeavour, in fact-possesses.

He may borrow his material, but he must colour it with his own experience of the medium.

Then, and only then, will the completed film be his own, as unmistakably as Kalidasa's "Shakuntala" is Kalidasa's and not Vyas's.

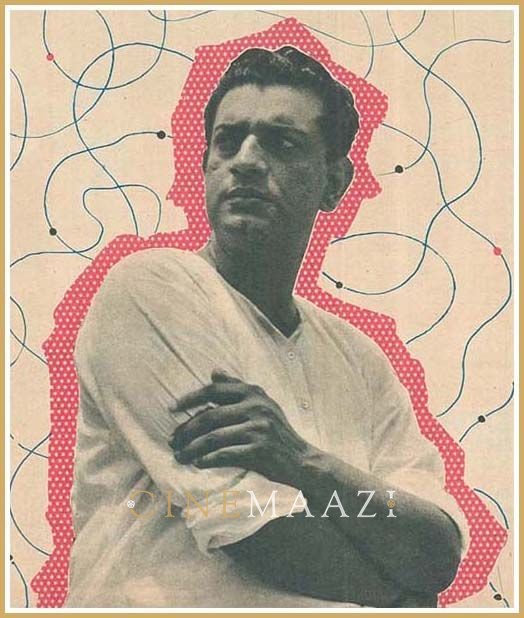

This article was published in Filmfare magazine’s August 28, 1959 edition written by Satyajit Ray.

The images appeared in the feature are taken from the original article or Cinimaazi archive.

About the Author

.jpg)