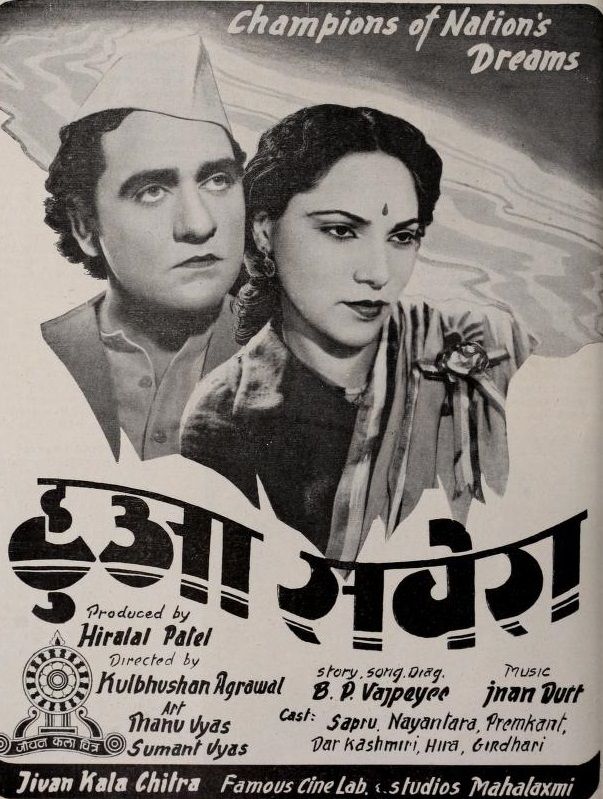

"Hua Savera", An Unholy Hotch-Potch On Freedom Theme

That the advent of Indian independence has enabled our producers to tackle freely all those subjects and display of our national leaders which used to be a taboo to our alien rulers, needs no emphasis. But if this only means that the producers are given full liberty to picturize any humbug or trash in the guise of freedom themes and especially to exploit unblushingly the photographs, newsreels, etc., parading our national leaders with a view to secure the sentimental sympathy (and clapping) of the spectators, then the sooner our censors saw through the game and discouraged this vogue, the better it will be for all concerned. Let us learn to respect our national leaders better than to turn them into dumb salesmen of rotten motion pictures.

Hua Savera (1948), released simultaneously at four city and suburban theatres, is one such hackneyed and abortive attempt to link up some stray shots of our national leaders and events like the celebrations of 15th August 1947 with a pretentious, flimsy and utterly stupid story which has no semblance of drama, novelty or originality and goes almost begging for other ingredients as well.

TALE OF TWO BROTHERS

The picture opens with Netaji Bose delivering a speech followed by a few more borrowed scenes relating to the freedom struggle culminating in the achievement of 15th August on which day the hero, Prakash, is set free from the prison where he was probably interned because of his progressive, revolutionary and anti-capitalistic ideas.

The story (if at all it could be so called) then proceeds on the oft beaten track where we find two Zamindar brothers who are an antithesis of each other with only the heroine as the common target of their life! Ajit, the younger one, is the villain-of-the piece typifying all the vices and evils supposed to be inherent in a zamindar aided and abetted by his Munimji while the elder, Prakash, is out to democratise the old order and ameliorate the lot of the peasants by initiating reforms, a la the Congress.

Alongside the inevitable clashes between the two brothers run their respective romantic interludes and the all-too-familiar squabbles shorn completely of any dramatic intensity or force of characterization, with the hero delivering tall sermons and irrelevant lectures in the name of "Azad Hindustan" until it all ends well with the "dawn of new era transforming Ajit from a scheming, inveterate scoundrel to a good boy standing next to his brother for fag salutation !

With their woeful inexperience of film technique and despite all their good intentions behind this maiden venture, both the producer and the director have made an unholy hotch-potch with no entertainment and only a pretence of purposefulness. A mere background of 15th August and an indiscriminate use of the old scenes showing the national leaders may merit a few cheers from the undiscerning audience but it constitutes a criminal waste of celluloid against a mediocre theme and all-round poor production values with the exception of Fali Mistry's photography which is the only bright patch and saving grace of the whole picture.

NARCOTIC NAYANTARA

Director Agarwal has proved himself an out and out novice by betraying his colossal ignorance of film craft as there is little tempo and no continuity in the film produced under the high-sounding banner of Jeevan Kala Chitra.

Nayantara as the heroine fails to impress from start to finish with her repulsive looks, awful accent and narcotic acting. If her performance in Hua Savera is any criterion of her talent, it speaks little for those who have been shouting loudly of her star value. Adding to the eye-sore created by this girl is the miscasting of Sapru who is anything but suitable to be the hero and no wonder he fails miserably in the picture. Dar Kashmiri as the second villain and Hira Savant as Rekha do their bit though their contribution is like an oasis in a desert.

Barring one chorus which pleases the ears, the music of Gyan Dutt has nothing to write home about and the recording is too bad and faulty throughout for words to express. Thus, far from entertaining, Hua Savera only helps to provoke the question: Is it desirable to exploit national leaders (including Gandhiji) on the screen on the slightest pretext and without much rhyme or reason merely because the producers wish to cash the prevalent patriotic sentiment and while making fools of the spectators also lower our national heroes in the estimate of millions? Let Mr Morarji Desai pause and think.

This review was originally published in Film India's 1948 issue.

About the Author

.jpg)