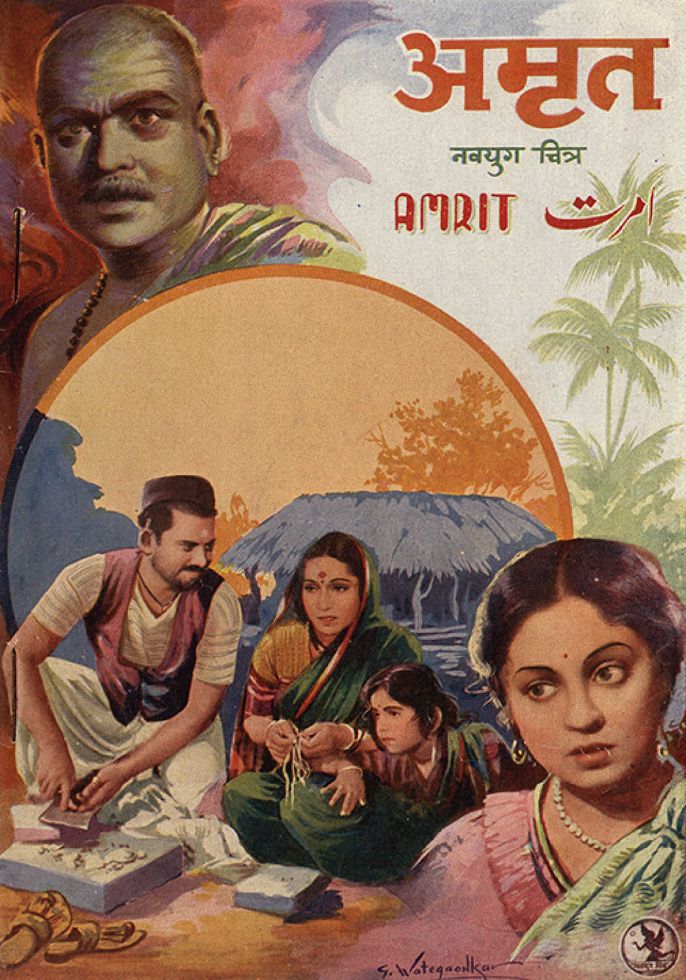

“Amrit” Becomes A First Class Picture

29 Aug, 2020 | Archival Reproductions by Cinemaazi

Image credit: Cinestaan

Lalita Pawar and Baburao Pendharkar Shine

An Entertaining & Instructive Picture

The picture opens with a very high flown ideal of “God creating the world and expecting the human beings to live in it in a loving brother-hood etc., etc., and then suddenly the theme deteriorates and dissolves itself into a prohibition campaign against toddy and liquor drinking.An Entertaining & Instructive Picture

Khandekar’s erratic treatment of film plots is not new to us, but in this one, he scores a remarkable hit by thinking of one thing and writing about another, so completely different. It is the directorial genius of Vinayak that saves Khandekar from himself.

The name “Amrit” is the least consistent part of the picture which should have been called “Jamuna, Chamarin.” The picture would then have secured a little more human appeal.

A STUPID PROCEDURE

The story cannot be told in detail here because the names of the characters are different in the two versions, Marathi and Hindusthani. This is at best a stupid practice which only helps in revealing to us the bankruptcy of brains in the writers who, it seems, cannot find names which can be common and yet popular for both the versions. If these different names are given to

Stress the individuality of the version writers, it is a regrettably stupid indulgence in conceit which only helps to create confusion. I shall therefore relate the story in symbols and signs. There is a rich landowner with as a daughter and a friend of the son thrown as grace on this side. On the other side of the fence are a shoe-maker, his beautiful wife and a smart little daughter. The first party is rich and the second party is poor. The second party, moreover, is addicted to drinks thereby giving the son of the first party a chance to make some indecent proposals to the wife of the second party.

But the wife of the second party spurns the man inspite of her own husband being irresponsible.

The name “Amrit” is the least consistent part of the picture which should have been called “Jamuna, Chamarin.” The picture would then have secured a little more human appeal.

THREE-IN-ONE AFFAIR.

The story seems to be having three themes—(1) an illegitimate romancing between the rich man and the poor beautiful woman (2) pointing out the social evil of drinking, (3) and the eternal clash between the rich and the poor. The original paper theme of “God creating a world etc., etc.,” dies with the title. And the three themes which rush in and out of the reels never catch up with their justification completely at any stage.

The prohibition scenes are made unreal the dramatic and look very exaggerated. The song sung by the toddy drunkards popularizes toddy drinking. If toddy drinking people can sing so well after all the toddy that is sent in, it is not at all a bad job drinking toddy. The song, therefore, fails in its desired effect.

Vinayak and Meenaxi are absolutely unnecessary for the main story. In fact, they could have been entirely removed and the story would have improved considerably. In the direction of Meenaxi and himself, Vinayak commits the very same mistake which Shantaram has committed in Shejari (1941). For some reason best known to Vinayak, Meenaxi’s scenes are unnecessarily pulled out and made boring. If the idea was to put Meenaxi on the screen as much as possible to make her more popular, it has failed in its purpose as Meenaxi, having no logical existence in the whole plot, becomes, at best, a drag on the otherwise fast tempo of the story.

VINAYAK ON SUICIDE PATH.

The love antics of Meenaxi and Vinayak cannot be called acting. Their sequences at best become a crude pantomime of sex-starvation certainly a poor show for an intellectual like Vinayak. Vinayak must make up his mind whether he wants to produce a picture for its own sake or for the joint interests of Meenaxi and himself. He is falling into an easy rut that leads to the suicide of a career.

Meenaxi is the sex-starved daughter of the rich Hindu landlord, evidently from one of those so-called higher communities. She is a grown-up woman, who is shown as tickling her sex with some suggestive paintings. Imagine her-a Hindu eligible girl-singing a song of her empty bed and herself thirsting for a mate. The song, Meri Suni Sej Pady is vulgar and suggestive. Its Marathi version, however, is thankfully toned down.

The whole picture is shot in delightfully pleasant and rural surroundings which by their very natural grandeur take the vote spectators.

Reverting to the story, the landlord of the first party is found exploiting the poor people of the village. Idioms and parables of social philosophy soon fill the air like sparks but they fail to light up anything. All the social philosophy is wasted as the drama centres mainly round the individuals and fail to touch the community. The theme. The problem or the intention, whatever it is, that inspires the picture does not go beyond the embryo.

The rich son’s romantic leanings for the poor shoemaker's wife are soon turned by the crafty poor into an expose which brings the rich landlord to his knees. Quite too suddenly, this man who had amassed money all his life by hook or crook. turns the corner and becomes a different man. And for this a convenient storm is used, a little child is sacrificed and the face of Shiva’s image is also lighted by the lightening. Nowhere are the intrinsic truths in the philosophy given a chance to convince or convert the man who had to be made human by storms, sacrifices and other melodrama.

As is expected, the story ends with good cheer for all.

A DIRECTOR’S PICTURE.

Forgetting for a while the fundamental defects in the story, which are all of the story writers creation. The director has done a really swell job of it all by lending it a fast cinematic tempo, particularly in the last six reels, and in maintaining audience interest by dovetailing entertainment and melodrama. It is a director’s picture every inch of it, and quite his very own in the first four reels where Vinayak and Meenaxi give some mixed sex-play.

The photography is decidedly beautiful, particularly the artistic framing of the outdoor shots. The whole picture is shot in delightfully pleasant and rural surroundings which by their very natural grandeur take the vote spectators.

The first five reels called for a little more care in sound recording.

VINAYAK AND MEENAXI DISAPPOINT.

There is little to choose between Lalita Pawar and Baburao Pendharkar. Both are superb and well cast and well-matched. Salvi comes close to giving an excellent performance as the rich landlord. The disappointments of the show, however, are Vinayak and Meenaxi. They were in the picture without any reason for their stupid performance. Both seem to have forgotten to act and keep on looking at each other a little too much and a little too affectionately.

And yet, after all, done and said, “Amrit” still remains a first-class picture and as there is plenty to entertain and to learn in those fifteen reels of celluloid, you cannot afford to miss this picture.

This article is a reproduction of the review published in Film India in July 1941.

About the Author

Other Articles by Cinemaazi

17 Feb,2024

What is a Good Documentary Film?

25 Jan,2024

Salute to an Immortal Spirit

22 Jan,2024

A Painful Parting

29 Nov,2023

Children's Film Society

28 Oct,2023

Let's Give the Kids a Chance

26 Oct,2023

Directing the Child Actor

25 Oct,2023

Chandu - The Elephant Boy

23 Oct,2023

HEROISM-Children's Film Society gives the lead

18 Oct,2023

Munna

29 Sep,2023

ख्वाजा अहमद अब्बास का पत्र महात्मा गांधी के नाम

02 Sep,2023

Shakti Kapoor: It's Three Punches A Day

04 Jul,2023

Should a Filmmaker be Original?

24 Jun,2023

Babita My First Screen Love

22 Jun,2023

Phir Wohi Dil Laya Hoon

19 Jun,2023

Romance in Our Cinema

12 Jun,2023

The Romance of our Show Houses

12 Jun,2023

Kashmir Ki Kali (1964)

07 Jun,2023

Sangam (1964)

05 Jun,2023

This thing called Love

25 May,2023

Gandhi: Whose voice?

15 May,2023

"Deewar" Becomes a Nation's Prayer

15 May,2023

Mangal Pandey

06 May,2023

History of Cinema, History of the Nation

02 May,2023

Birbal Paristan Mein

20 Apr,2023

Reincarnation... the story goes on ever after

27 Mar,2023

The Film Director?

21 Mar,2023

M Sadiq

15 Mar,2023

The Social Role of the Cinema

15 Mar,2023

"Samaj" A Memorable Film with Popular Appeal

01 Mar,2023

"Two Eyes" in Hollywood

20 Feb,2023

Do Dooni Chaar

15 Feb,2023

Rafoo Chakkar

07 Feb,2023

Johnny Walker.... still going strong

20 Jan,2023

Mahabharat : Epic Tamasha

10 Jan,2023

Narsi Bhagat : An Excellent Biography

03 Jan,2023

Nav Ratri

01 Dec,2022

एक ताजगी का नाम है देवानन्द (Dev Anand)

25 Nov,2022

जे बी एच वाडिया (J B H Wadia) - वचन न जाए

14 Nov,2022

Children's Films in India

01 Sep,2022

Horses .... Cars and Laughs-Mehmood

06 Aug,2022

हिन्दी फिल्मों की दुर्दशा का जिम्मेदार कौन?

01 Aug,2022

क्या हिंदी फिल्मों से हास्य गायब हो रहा है?

20 Jul,2022

हास्य की परंपरा और हास्य अभिनेताओं की भूमिका

12 Jul,2022

प्राण और उनकी दाढ़ियाँ

17 Feb,2022

Odds Against a New Comer

10 Dec,2021

Speaking of Portraits and People

03 Nov,2021

An Actor Prepares

19 Oct,2021

Producers' War on Dubbed Films

24 Aug,2021

Jottings from a Film Director's Notebook

26 Jul,2021

प्रेमचंद सत्यजीत राय और ’सद्गति’ -गिरिजाशंकर

22 Jul,2021

Rewind 1990 Commerce of Love Stories

20 Jul,2021

Eastern Scene: Cinema of Surviving Faith

22 Jun,2021

Movie Memories : Tansen (1943)

22 Jun,2021

Movie Memories: Sikandar (1941)

15 Jun,2021

Towards A Brighter Future- Bengali Cinema

20 May,2021

The Enigma Of A Flux - Malayalam Cinema

05 May,2021

The seesaw graph of Hindi filmdom

03 May,2021

Ankahee: The Unspoken

29 Apr,2021

The Mahatma Returns: World Press Reaction

29 Apr,2021

Children’s Films

17 Apr,2021

Telugu Cinema in 1986- Sons and Fathers

09 Apr,2021

Mukhamukham : Face to Face

08 Apr,2021

Tarang : Wages and Profits

01 Apr,2021

Design In Indian Cinema

27 Mar,2021

Movie Memories : Savkari Pash

23 Mar,2021

Double Trouble: Role of Twins In Hindi Cinema

22 Mar,2021

Prem Chopra: The Same Role For Ever

19 Mar,2021

Kalyan Kumar - Karnataka’s Self-Made Star

18 Mar,2021

Ceylon's Cyclonic Cinema

18 Mar,2021

Movie Memories : Aladdin & the Wonderful Lamp

17 Mar,2021

Kumari Padmini: Rising New Star Of The South

11 Mar,2021

50 YEARS OF MALAYALAM CINEMA

02 Mar,2021

Alakh Niranjan: Film India Review

27 Feb,2021

Party: The Story of Choices

26 Feb,2021

The Naushad Era In Hindi Film Music

19 Feb,2021

A Man: Amitabh Bachchan -Amitabh, is My Name

10 Feb,2021

A Man: Amitabh Bachchan - Two of a Kind

29 Jan,2021

Women In Hindi Films : Dichotomy of Values

22 Jan,2021

A Man: Amitabh Bachchan - Yesterday and Tomorrow

22 Jan,2021

Cinema in the South: Crisis of Character

18 Jan,2021

Film Societies Play Their Part

01 Jan,2021

Nutan : A Flashback - The Actress

30 Dec,2020

"Gwalan" Proves A Thrilling Entertainment !

29 Dec,2020

Rajesh Khanna : Echoes Of An Era- Family Of Four

28 Dec,2020

Holi: A Metaphor for Horizontal Violence

23 Dec,2020

A Summon for Mohan Joshi

22 Dec,2020

Nutan : A Flashback - The Friend

22 Dec,2020

Raj Kapoor Scores Personal Triumph In “Aag”!

19 Dec,2020

Smita Patil's Memoir- Trading Places

17 Dec,2020

Shashi Kapoor: Once Upon A Time- The Film Makers

16 Dec,2020

Rajesh Khanna : Echoes Of An Era- Peer Pressures

15 Dec,2020

“Lal Haveli”- Crude But Entertaining!

12 Dec,2020

Nutan : A Flashback - The Wife

10 Dec,2020

Rajesh Khanna : Echoes Of An Era

09 Dec,2020

"Lalkar" Presents Cheap Entertainment

07 Dec,2020

Smita Patil's Memoir-Comrades In Arms

01 Dec,2020

Shashi Kapoor: Once Upon A Time- Unjinxed

28 Nov,2020

Ek Din Ka Sultan- Becomes Good Entertainer !

26 Nov,2020

Smita Patil's Memoir- Friendly Strokes

25 Nov,2020

Shashi Kapoor: Once Upon A Time- Tough Times

07 Nov,2020

The Technician And His Problems

06 Nov,2020

We Must Inject Dynamism Into Publicity

05 Nov,2020

The Role Of Film Finance Corporation

04 Nov,2020

Progress In Raw Film

30 Oct,2020

Freedom In Films

28 Oct,2020

Export Market For Indian Films

23 Oct,2020

The Growth of The Motion Picture

22 Oct,2020

Setup Of The Film Industry

21 Oct,2020

Few Facts About Film Production

13 Oct,2020

Personalisation In Cinema

08 Oct,2020

Waiting for a Doyen's Glance- Arati Bhattacharya

08 Oct,2020

कौन सुनेगा इन सिसकती बिलखती प्रतिभाओं का विलाप?

06 Oct,2020

Asrani - Laugh And The World Laughs With You

05 Oct,2020

My Memorable Roles- Hiralal

03 Oct,2020

राजीव गोस्वामी - कहां थे अब तक 'पेंटर बाबू'?

03 Oct,2020

जब नफरत से बेड़ा पार हो गया: बलराज साहनी

30 Sep,2020

The Case of Emotional Turmoil In Dopatta (1952)

29 Sep,2020

The Story Of A Child Artiste - Sheela Kashimiri

26 Sep,2020

Afsana Likh Rahi Hoon : Tun Tun

26 Sep,2020

Some Hopes For The New Year: Lillian

24 Sep,2020

Joru Ka Bhai: A Tale of 'Atithi Tum Kab Jaoge'

22 Sep,2020

अभिनेता प्रेमअदीब से भेंट

21 Sep,2020

Vijaylaxmi: A Career As The 'Other' Woman

18 Sep,2020

Shaminder: The Actor Who Had High Hopes

16 Sep,2020

धर्मेन्द्र - समय आ रहा है...

14 Sep,2020

Film Life After Fifty : Motilal

14 Sep,2020

प्रसिद्ध फिल्म लेखक गुलशन नंदा से आपकी बातचीत

11 Sep,2020

"I live on hope"- Kumkum

11 Sep,2020

Thehr Zara O Jane Wale : Madhubala Jhaveri

09 Sep,2020

Ratnamala Attracts Attention In ‘Station Master’

08 Sep,2020

Ghory: The Laurel Of Indian Cinema's Comedy Duo

07 Sep,2020

Yeh Teri Saadgi, Yeh Tera Baankpan: Usha Khanna

07 Sep,2020

सेनापति शेट्टी

05 Sep,2020

कृतिदेव यहां मैं, तनूजा, स्वीकार करती हूँ

05 Sep,2020

मै उर्मिला को भूल नहीं पाती - मंजरी

04 Sep,2020

बुलबुल बंगाल की: चंद्राणी मुखर्जी

03 Sep,2020

Payyal's Lucky Break

02 Sep,2020

These Foreign Producers

29 Aug,2020

The Practical Actress: Shabnam

28 Aug,2020

फिल्मी मारपीट के गुरू : अजीम भाई

26 Aug,2020

From Poverty to Screen Fame - Mehboob Khan

26 Aug,2020

Humility: Nasreen's Most Admirable Feature

24 Aug,2020

A Mercenary Comes To India - Bob Christo

23 Aug,2020

Dilip Kumar: The Leader

19 Aug,2020

Alam Ara: Ardeshir Irani's Ambitious Secret

17 Aug,2020

I Serve My Art- Kanan Devi

10 Jul,2020

.jpg)