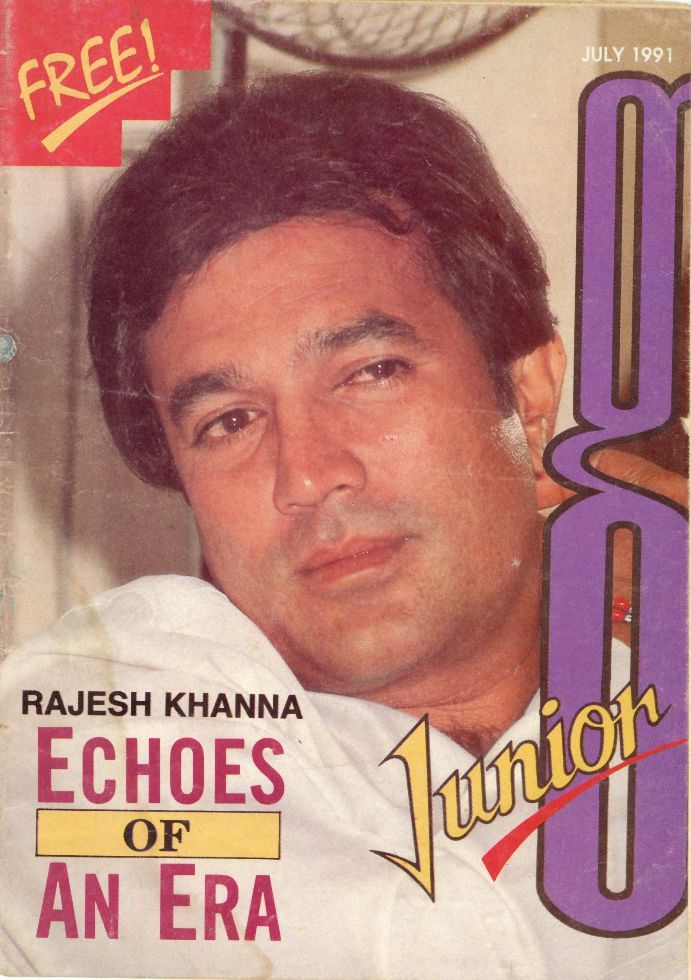

Rajesh Khanna : Echoes Of An Era

I was born to my parents after eighteen years of marriage. After three daughters, they were very keen on a son and my mother, I am told, organised a special havan for this. No wonder then that I was an exceptionally pampered child. Those days they believed that the later they got the child's mundan done, the better it was for his health. So, my mother who was extremely superstitious, to ward off the evil eye, avoided doing my mundan until I was two years old. Now, according to the custom, the child who hasn't got his mundan done cannot be dressed in stitched clothes. As a result, I was forever clothed in silk fabrics, much to my mother's displeasure. She felt very deprived that her only son should be dressed incompletely "Wait till his mundan is done," she would always say, "and I'll show the world what a wardrobe I can organise for my son." When the time came, she personally sat and stitched my clothes -- little bandis with embroidery and kurtas with zari kaam. My fascination for clothes started that early Even as an infant, anything ordinary wasn't good enough for me. And how could it be, considering I was reared in princely surroundings. My parents always made me feel very important.

My naming ceremony was performed in Dhapalpur, a small village of Karachi inside our kuldevta's temple. Even today, when I pray, I am somehow mentally communicating to the God inside that temple. My parents named me Jeetendra', but nobody ever called me by that name. In the house, I was always referred to as 'Kaka'. 'Kaka', up North is a very common pet name for the youngest child in the family.

The only time, my mother yelled at me was when I refused to drink my milk. I hated drinking milk and looked for ways to avoid the tall glass coming my way. Everyday, my line of excuse changed. One day I felt nausea. One day giddy. One day it was a stomach-ache and on another, a headache. Each time, however, my mother was one up on me. "You think you can fool Leelavati, do you?" she would say Holding me tight by the arm, she'd clasp my nose and force it all down my throat. I hated the moment. I hated both, the smell and the taste of it. But there was no escape. The doctor had convinced my mother that the only way to improve my weight was by giving me lots of milk. So paranoid was she about my drinking milk that she had even consulted pundits. One pundit suggested to her that if she served a cup of milk to a black dog everyday, chances were that her child would start liking it himself. So everyday, a servant was sent hunting for a black dog. It sounds crazy, I know, but that's how obsessed she was with me.

From the very beginning, our family was deep into rituals and traditions. I guess that is why I am so religious. My parents often kept chandi paath at home. In the year I was to be born, they organised a paath that ran through all of the twelvemonths and my busy father, who was a workaholic began leaving his office early, so that he could personally shop for my belongings. Even the pacifier I used, was obtained from London.

As I grew older, I got used to getting everything I wanted. Once, I had gone to Delhi for my summer holidays where I learnt cycling. When I returned, I asked my mother to buy me a bicycle. She refused. "It is dangerous on the roads," she explained. I began to howl as if the world had come to an end. To pacify me, she spoke to my father. My father was furious that my mother could even entertain the thought. "Cycle, for a child in a city like Bombay!" he thundered. That should have been the end of the chapter, but stubborn that I was, I persisted. Exasperated, my parents relented. But on two conditions. One, I would ride my cycle only inside the garden and not on the streets. Two, I would not ride the cycle, after it was dark.

.jpg/Pics%201%20(3)__201x480.jpg)

Initially, I kept to my promise but gradually as months passed by, I became more and more adventurous. One day, I got so carried away, that I went for a long ride along with a neighbourhood friend. When I didn't return until dark, my parents got worried and sent servants to search for me. When I got home, it was past 8 p.m. I can never forget that evening. Father was by the window, angry. Mother was sitting in a corner, weeping. As soon as she saw me, she broke down and ran forward to embrace me. But father didn't let her. He first fired my mother and later me. Prior to this, my father had never fired me. Never raised his voice, but today he raised his hand too. I was given a beating I could never forget. I felt scared, tired, hungry and in my nervousness, I peed. My mother was instantly protective. "Can't you see the boy is frightened?" she told my father "He better be," my father yelled, angry with her for intervening...

Another incident to shake me up emotionally was when I was about ten years old and had gone to my father's office. Home and office were close by and I was used to dropping in at the office to see father. That day, my father was in a meeting and asked his peon to make me sit in his cabin. It was common for me to lounge around in my father's cabin reading my comic books. That day too, I was carrying my comics with me. I plonked myself on my father's chair. Just then, my uncle (mama) K.K. Talwar, who assisted father in his work, entered. "Arre, Kaka, how come you are sitting on this chair?" he sounded alarmed. I looked at my uncle in surprise. "You have to first deserve it, only then can you sit on another man's chair!" Uncle seemed angry with me and his words were scathing. I felt hurt but more than that, I felt confused. What did uncle mean when he said 'deserve', I wondered. I wouldn't dare ask father for an explanation, for I didn't have the courage. But I asked my mother. "What is 'deserving' and why is it that a son cannot sit on his father's chair?"

On that day, mother told me something that I have never forgotten. And in her explanation, came a message of life. My father, it seems, was only ten years old when he lost both his parents. At this tender age, he was shifted to his aunt's home. One day, over some misunderstanding, he left his aunt's house never to return to it again. Accompanied by my mother, he came to Bombay, all set to start a new life.

Those were desperate days. They had no money, no home, no friends. Father rented a small room in Thakurdwar, even though he had no money at that time. Somehow, he managed to convince the landlord that he would work hard and pay him his rent. Somehow, the landlord trusted him. And my father didn't let him down. Within a month, father found a job as a supervisor that paid him enough to get him and his wife one meal a day For this, he had to leave early in the morning and return very late at night.

Mother came from an affluent family and was not used to hardships. Reared in comforts and luxuries, she had never known the meaning of struggle. But not once, during his struggle, did she complain or lose hope. On the contrary, mother happily supported him, boosted his morale when times became really bad. Because father could not come home for his afternoon meal, she skipped her lunch too. Both ate just once a day. That too late at night. Her sacrifice was natural. She wasn't even conscious of it. Her prayers were a conscious effort though. "If you don't forget God. He does not forget you." Her prayers didn't go unanswered. After years of struggle and toil, prosperity came my father's way And the triumph was cherished deeply because they had both worked very hard for it. Beginning as a supervisor and graduating to be a Railway Contractor, my father was now ready to launch his independent venture. One by one, he spread his companies outside Bombay First Madras, then Delhi and finally Calcutta.

"The 'deserving' your uncle mentioned to you about is your father's this struggle. He has poured his blood and brain for everything he possesses today For everything we enjoy today. The big empire he rules, is built on the foundation of hard work. As his family, we can enjoy the luxuries, but we have no claims on his glory His success, his position, is his own, and it is his greatness that he does not make us conscious of it."

The simplicity and the clarity with which mother explained this, made a deep impression on my psyche. After this incident, I never sat on anyone's chair again. Not even those inferior to me, for how could I be sure that I deserved to?

I got attracted to theatre while I was still in school. All the boys from the neighbourhood would collect on our building terrace and enact plays. WP drew up curtains with sarees stolen from our mothers' cupboard and created a stage out of discarded benches gifted by the shopkeepers. My favourite role, those days, was of a gypsy I longed to get into colourful costumes, longed to paint my face and mouth long dialogues. But more than anything, I loved watching plays. I never missed an opportunity of visiting the theatre. Slowly, however, as I grew older, films, began to replace my passion for theatre.

The first film I ever saw, must have been from my mother's lap, but the first one, I remember was A.R. Kardar's Dastaan (1950) starring Raj Kapoor Veena played a vamp in this film and God, what a vamp! She was so effective that years later, when I had to shoot with her for Do Raaste (1969), I was petrified of her I could not wipe away her stern memories of my childhood. I had a very evil image of her in my mind. But of course, she wasn't like that. Over the years, I learnt of course, that an actor isn't what he appears on the screen. His true personality, very often, is a contrast of what he projects in his films.

Strangely, those days, whenever I was asked what I would become when I grew up, I always said, "I'd become a pilot." This, even though it had been drilled into me since childhood that when I grew up, I'd have to join my father's business. I was only in high school, when my father opened an independent bank account for me. I could not operate the account, being still a minor, but all the same, the account made me feel very powerful. And I liked the feeling of power!

This article was originally published in a Junior G's supplementary issue -Rajesh Khanna: Echoes Of An Era- issue.

About the Author

.jpg)