In a democracy, every citizen can seek redress for a wrong done to him by going to the court of law. Such is his constitutional right. But the long arm of the law is rarely long enough to reach across a chain of cumbersome procedures, manipulated witnesses, ur scrupulous lawyers and indifferent judges, to bring justice to the Mohan Joshis of this world. In the ramshackle tenements of the great metropolis of Bombay families survive for generations in unhygienic conditions without uttering a word of protest, for the reverberations of such an act might bring the whole rickety structure crashing down on their heads, and what rights can a citizen have when he has no roof above his head?

Mohan Joshi is a foolish old man. He does not appreciate the fact that he is one of the privileged few who actually have a home to live in. So what if the sewage pipes leak on his head throughout the year, and the plaster peels off the ceiling without notice? It all begins when old Joshi is standing in the queue at the milk booth one day, when the man in front of him boasts how he has sued the landlord of his uncle, given the man something to worry about for years ! What a grand idea ! Why cannot Mohan Joshi demand that his landlord provides the minimum running repairs for a flat where the Joshi family has lived for three generations, and paid the rent regularly too?

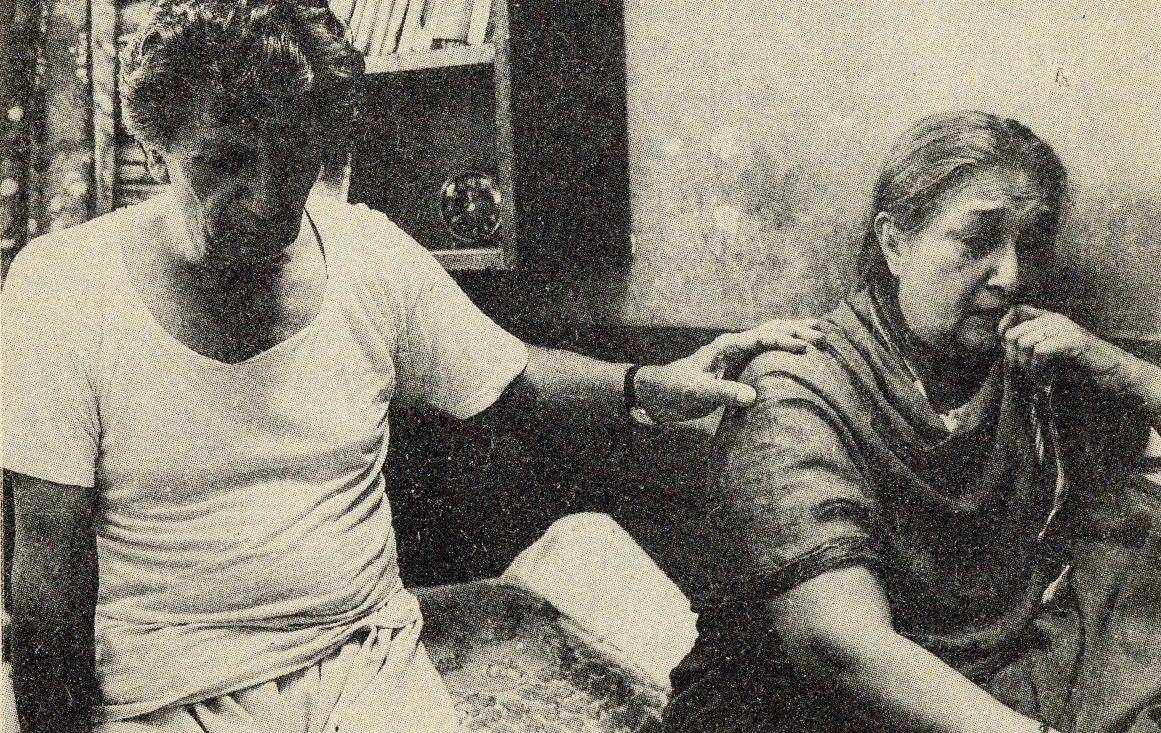

Joshi and his wife decide to meet the landlord first; give him a chance. But the greedy Kundan Kapadia, bloated with his already overflowing wealth, is surrounded by sinister building promoters. He will have more money when the tenements collapse and hi-rise buildings are constructed in their place. Insulted and humiliated, Mohan Joshi marches off in righteous indignation in search of a lawyer. His neighbours ridicule him, his family refuse to help him. Only his wife stands by the stubborn old man. Clientless lawyers pounce on the two old people like a pack of hungry wolves. Out of the fray, Gokhale and Malkani emerge the victors, and Joshi becomes their first client.

The battle begins. The case starts and stretches on as court cases do. The old couple part with their meagre savings and the old woman's last bits of jewellery. The slippery lawyers promise great results. But the days stretch to months, the months to years, without the day of reckoning ever coming within sight. The landlord hires Desai and Rani whose claim to fame lies in the fact that they can harass the opponent into submission, and this is what they set out to do. The Joshis are led a merry dance with an assault case and an eviction suit to complicate the original repairs case. The neighbours watch Joshi's humiliation with glee, some of them bait him mercilessly, and one vicious old man fills his pockets on the side by actively helping the landlord against Joshi. A further complication arises out of the fact that the old man's daughter and Joshi's younger son are in love, but dare not own it up in front of their elders. Threatened by the hired ruffians of the landlord and harassed by his smart lawyers, even Joshi's daughter-in-law and elder son join the battle.

In the meanwhile Malkani and Gokhale progress from a desk in the corridor to a luxurious office. Rani marries Desai, but carries on a clandestine affair with Malkani. Between the four of them the case carries on across time while the promoters wait patiently for their chance to build a sea of buildings from Bombay to Dubai. Judges come and go, and sections and subsections clash in mid-air in the courtroom. The Joshi family are tossed between impatience and total despair. Their tenement home creaks and groans under years of neglect. Even Joshi begins to see through the hoax.

.jpg/2%20(2)__600x393.jpg)

Finally, when the whole family starts bearing down on the lawyers, Malkani decides to make an unexpectedly passionate appeal in court, demanding that the judge sees for himself the state of affairs. The judge agrees, and the world changes colour for Mohan Joshi. All of a sudden his jeering neighbours turn into fast friends. Mohan Joshi has become a hero overnight. After all, the judge will not see the Joshi home alone. When redress comes, it will come for everybody. Mohan Joshi receives a standing ovation from his new friends. The mill of justice may grind slowly, but now there is no holding it back.

But the tenement dwellers have calculated without Kundan Kapadia and his slick lawyers. An army of workmen descend on the crumbling building, sweeping the dirt away, giving a lick of paint to cover the cracks on the wall, propping the disintegrating roof with painted poles. Though the tenants try their best to tear down any attempt at patching up the superannuated structure, the building wears an undeniably festive look when the judge finally arrives. The two sets of lawyers range on either side of the judge and carry on a slanging match. The tenement dwellers watch helplessly as the whole thing develops into one more interminable legal battle with the vacillating judge in its centre. In sheer desperation, the younger members of the Joshi family intervene to have a last hearing. But the judge is no longer interested in listening to what the dwellers of the tenement have to say. There is only one way left to Mohan Joshi. Putting all his frail strength together, he ends the dispute once and for all by pushing away the props that hold the building together, and allowing the house to come crashing down on himself.

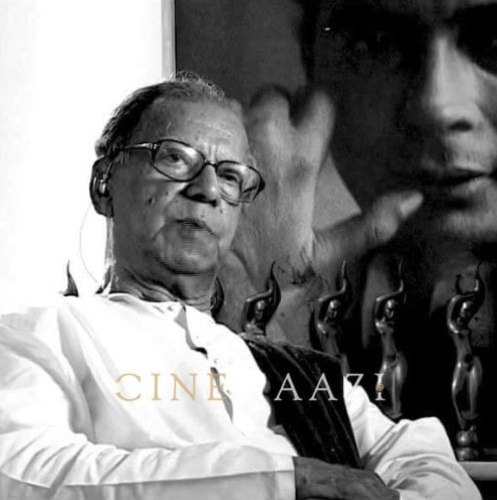

Born in 1943, Saeed Akhtar Mirza came to film-making after working for eight years in advertising. A graduate in film direction from the Film and Television Institute of India, Mirza has been a vociferous spokesman for the Parallel Cinema movement in India. He has directed four documentaries, three of which, Urban Housing (1976), Slum Eviction (1976), and Rickshaw Pullers of Jabalpur, deal with urban problems. His first, feature film, Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan (1978) received the Filmfare Critics Award for the best film of the year, and portrayed the alienation of an upper-middle-class urban youth. Mirza's second feature film, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai (1980), tackled the problems faced by a minority community in secular India. This film too has received the Filmfare Critics Award for the best film of the year. Mirza's concern as a film-maker is with creating 'a cinema of struggle as opposed to the cinema of the status quo.' His films are an attempt to evolve a form that is acceptable and has mass appeal, and at the same time opposes the status quo.

Talking to lqbal Masud for the Express Magazine,15 April 1984, Saeed Mirza expresses his views on his own films, particularly his third and latest feature film, Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho !

I.M.: How do you feel about your two earlier films,Arvind Desai and Albert Pinto ?

S.M.: I constantly refer back to them. I constantly re-analyse my position with regard to those films. About Arvind Desai; I had then come out of the Film Institute fresh and I made a film which was very classic in construction. I realise now that it is a film which could very easily be made by a person like me who had gone through an academic education about the theory of the construction and the structure of film. A lot of people say they prefer Arvind Desai to my other work. I know why. Arvind Desai doesn't take a leap into the realm of mistakes. Albert Pinto took that leap. There, I was bound to make mistakes. Albert Pinto's form was much more free. Arvind Desai was more strait-jacketed, more rigid. When one tries to break loose, there will certainly be pitfalls and traps.

I.M.: There are likely to be ideological changes in stance as well as changes in cinematic form. Is the former true in your case?

S.M.: Certainly. The kind of questioning I engage in is fundamental to my ideology.

I.M.: How did you see Mohan Joshi when you started the film?

S.M.: Mohan Joshi is predominantly an idea, and I have characters who make that idea sensuous. Mohan Joshi, to me, is the idea of decency. Sacrificed at the altar of pragmatism. Today, a man who tries to get a bus queue into line is derided as an idealist.

I.M.: Mohan Joshi has three worlds—the worlds of the chawl, the court and the landlord-promoter. Let us take the world of the chawl. This is a favourite hunting-ground both of 'commercial' and 'art' cinema. How did you ensure that your chawl did not fall into one of the familiar grooves?

S.M.: The nature of the chawl has to be understood as an idea. The idea of pragmatism has also seeped into this chawl. The outside world is impinging on the inhabitants of the chawl. Everybody in this chawl has become pragmatic, except for an old man called Mohan Joshi. The other people in the chawl do not see why a man should fight at this level for what he calls his dignity. The only occasion [on which] they change is when they see the future changing, thanks to this old man, and suddenly [they] make a hero out of him.

I.M.: In Arvind Desai and Albert Pinto you stressed the danger of going it alone. Here, you stress the importance of individual conduct and initiative, of ethics and courage.

S.M.: My stance is that I would leave the collective aspirations to the audience. I have certainly shifted the emphasis in Mohan Joshi to the conduct of an individual, Mohan Joshi, hoping it will affect the audience.

I.M.: The influence of Brecht (I mean both his life and works) and of generally left-wing politics has overemphasised the role of history and of group effort and has liberated the individual from the burden of responsibility and ethics. Perhaps this tendency needed to be corrected and I am glad you have done it. Coming back to Mohan Joshi, towards the end of the film, he develops mythological overtones.

S.M.: Mohan Joshi is mythological. To me, he is Bhim and Samson combined. I use mythology not in its obscurantist form, but as a cross-reference in today's context. Today, the entire world--specifically, Bombay city—is working towards a kind of desensitisation to its own living conditions. To this, Joshi says: No. He is not a conventional hero. He is an old pensioner. He is not eccentric, he is demanding what everybody needs to demand- dignity according to our Constitution.

.jpg/3%20(2)__600x439.jpg)

I.M.: Why does Mohan Joshi alone possess this kind of fire?

S.M.: There was an explanation in the first shot. Joshi is the kind of man who has always complained, but by the time the film opens he is reduced to a whining old man. That is how his 'pragmatic' neighbours have come to see him.

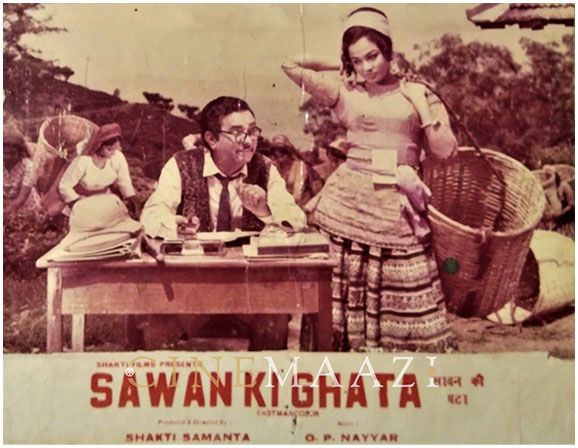

I.M.: Placing a seemingly prosaic old couple at the centre of action is certainly original and bold. Against them, you have set up the farcical, caricatured lawyer team of Naseeruddin Shah and Satish Shah. Farce and comedy are new elements in your work.

S.M.: I felt I should play with that idea in this film. I thought tragicomedy would push the basic idea in the film a little further. The lawyer team exploits the Joshi case not only to make money but to zoom off into politics, into another realm altogether.

I.M.: Despite the caricatures, there is a greater degree of realism in Mohan Joshi than in your earlier films.

S.M.: That is correct. What I am trying to do is to understand the courts in their essence. When you extend the logic of the court, it becomes a circus. What are our courts? Whose functions do they serve? I am trying to show the grotesquerie of the courts without losing realism.

I.M.: At the same time you do not caricature the day-to-day execution of justice but bring out its limitless possibility for delay.

S.M.: And this possibility is backed by law, this dragging through, this stripping of a person.

I.M.: The role of the lawyer, Malkani, played by Naseeruddin Shah is, I think, a triumph.

S.M.: Malkani represents the inexorable logic of desensitisation. I have observed such lawyers closely. They have a rationale for existence. They really believe in what is called law. Of course, in their minds, there may not be a coincidence between law and justice. There is a separation here and they live with that separation.

I.M.: There is a continuity of approach in this film from your earlier films in that you are not too interested in the intermeshing of individual relationships.

S.M.: No, I am not interested. What I am interested in is the fact that the reference point of the individuals in this film is Mohan Joshi. Mohan Joshi is the butt of their cynicism. That cynicism is destroyed only when they feel a change in their lives may occur because of Joshi—that is, when the judge decides to visit the chawl.

I.M.: The ending of the film suggests that even in the morass of our legal system there is some hope of justice if one persists.

S.M.: We have individual lawyers, individual judges, who are doing a fantastic job. But, by and large, the system stands for inhumanity towards the weak and the oppressed.

I.M.: That conclusion and the thrust of the film, aren't they rather pessimistic?

S.M.: If one can question the rhetoric of the layman, that by itself, is something. There is a position of power and a position of non-power. Through the law, a position of power can be assumed depending on who is exercising law.

I.M.: You have shown the people of `non-power', the chawl people, as incapable of co-operation. Will they ever convert their position into that of power?

S.M.: Not in the film, but outside of it. I cannot provide the solution within the structure of the film. The ball is in the audience's court- now what?

I.M.: The third segment of the film, the world of the landlord and the promoter, entirely caricatures. There is no attempt at realism.

S.M.: There is a new trend in this kind of exploitation. It is faceless and impersonal. How did the Cuffe Parade and Nariman Point complexes come up? Do we really know what forces are at work? There are specific individuals who manipulate but they remain faceless. That is why I have made the landlord (Amjad Khan) a caricature and the promoters human robots. They are beyond the pale of normal logic.

I.M.: Let us turn to your general approach to cinema. I think your cinema is not 'artistic'. It is the adversary cinema, an adversary to commercial cinema.

S.M.: There is a cinema of status quo and a cinema of change. That is the polarity. There is a kind of cinema which exists in a certain kind of political state. There is a direct correlation between the two. That kind of cinema produces the young 'romantic' couple in this film—frozen and static in their attitude to life. They do not represent the future; the old man represents the future. I have reversed the usual position. I am talking about generations. In the 1947 generation (that is, which was young at Independence) I feel there was some dignity, some calibre.

I.M.: I am surprised to hear that.

S.M.: There is a law of underdevelopment. There is a clear decline of leadership in all fields in underdeveloped countries after Independence. Expediency and hypocrisy flourish. Where is enlightenment today? All this is reflected in Mohan Joshi. Still, you will see that one segment of youth takes over the torch from Mohan Joshi.

I.M.: A final comment. At the moment, the subversive content of your films does not hurt the structure at which it is aimed. Your films are tolerantly regarded as 'angry films'. A time will come when that kindness will disappear.

S.M.: I am aware of it. I am aware of my precarious position. But if Mohan Joshi can stand, I can stand.

This article was originally published in the Indian Cinema's 1984 issue. The images used in the article are taken from the original article.

.jpg)