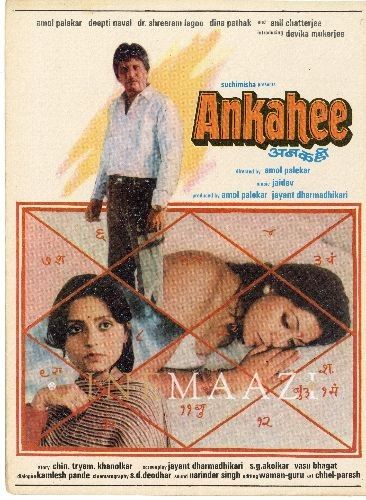

Human beings live and die without any sure knowledge of what the future holds for them. Ankahee (1985) tells the story of a group of individuals who are forced to survive or die battling against a prediction that must come true. The unknown powers that mould human destiny do not provide a reason why an individual must tread the path that he does all through his life. He takes his journey blindly, with no awareness of his destination. Perhaps that is the way it ought to be. The twists and turns of the path hold surprises for him, so that he may yet live in hope. If danger threatens, he has no knowledge of it till it is upon him.

But Nandu has been given that fatal knowledge of a dangerous corner in his life. Moving down the predestined path, Nandu yet struggles against that which is inevitable. His father, a well-known astrologer, finds himself helpless against a tragic, preordained destiny that he is allowed to see but not change. He starts questioning the value of his special powers. A vision of a tragic truth must remain an end in itself so long as the man with the vision is powerless to transform that truth.

Nandu has always been a nonbeliever. Even when his father's predictions invariably come true, he prefers to keep an open mind about why events take the turn that they do. He secretly resents his father's powers, finding in them a latent destructive force, for though his father foretells tragedy, he is unable to help in averting it. But otherwise Nandu is not an unhappy man. There is Sushma, an attractive young working woman, whom Nandu wants to marry. She is a woman with a mind of her own, and like Nandu, completely free of any fear of the unknown forces that his father believes in. But the old man's predictions hang like a dark cloud over Nandu's life while he, uncaring, brings Sushma home to meet his mother.

Nandu's father refuses to allow the marriage to take place. He would rather keep his secret knowledge to himself, but Nandu and Sushma demand a rational explanation. The old man has no rational explanation. He only has his knowledge that Nandu's first wife will die in childbirth. Will Nandu take on himself the responsibility of Sushma's death? His father has never been proved wrong, not once, and Nandu is tortured by doubts. But Sushma, a confirmed rationalist, refuses to believe in the inevitable. And if indeed she is to die, let her experience the happiness she craves for with the man she desires. Nandu cannot accept such a solution. He is trapped between his love for Sushma and his fear of his father's vision.

Nandu's obsessive fears have reached their peak when Indu comes into his home. The daughter of a childhood friend of his father, Indu's psychological imbalance has caused her to confine herself mentally within the limits of an innocent childhood. Her father, at one time an exponent of classical music, is now older than his years, his voice muted, forever anxious about his daughter's future. But Indu sings his songs, expressing a childlike wonder at every flower, every bird. The fears that plague her suddenly on occasions, transforming her lovely face into a withered, shrivelled mask, slowly start fading away in the benign presence of Nandu's father and with her increasing emotional security in Nandu's home. Indu is taken to a psychiatrist who, to the delight of her father, pronounces her curable. Indu herself is happy to be away from her village home where her attacks of instability were treated brutally by the local witch doctor, an experience which only helped to strengthen her sense of insecurity.

As Indu and her father live in hope in Nandu's home, Nandu's warped sensitivities work out a plan to circumvent his father's prophecy. He will marry the helpless Indu, and when she dies in childbirth, he will be free to take a second wife, Sushma, the girl he loves. Sushma, horrified by the change in Nandu, refuses to fall in with his plan, and stops seeing him. She has met Indu and cannot reconcile herself with the idea of allowing the helpless young girl to die an untimely death only to keep herself alive. She herself cannot believe in the prediction and is willing to take the risk and marry Nandu. But the responsibility of someone else's survival is too much for her to shoulder.

Indu's father is so happy when Nandu tells him of his wish to marry his daughter, that the old astrologer and his wife find themselves powerless to stop the flow of events. Indu, who is already spontaneously attracted to Nandu, is on the path to complete recovery .The marriage takes place. Nandu finds himself unable to undertake the final act of treachery towards his innocent wife, and refuses to sleep with her. But after a final stormy meeting with Sushma who now feels that the shadow of Indu will always be between them, Nandu comes home and makes love to his wife. The relationship develops and in spite of himself, Nandu finds himself getting emotionally involved. When Indu is pregnant, Nandu feels it imperative that he should be honest with her. The knowledge of her tragic fate gives the now completely normal Indu a strange feeling of peace. In a short span of eleven months she has been given a lifetime of happiness and fulfillment, something she had never hoped to achieve, lost as she was in her shadow world. In the last stages of her pregnancy she goes to visit Sushma who has now completely withdrawn herself from Nandu's life. She has come to say goodbye, and to tell Sushma that the happiness that has been hers, she now willingly hands over to Sushma's care. The labour pains begin and Sushma rushes Indu to the hospital herself, but leaves after informing Nandu.

Now that tragedy is upon them, each person reacts in a different way. Nandu waits anxiously, his mother waits in sorrow. The old astrologer prays for the destruction of his powers of prediction. Let him be proved wrong this once. Indu survives. She is well and cannot believe that the ordeal for which she had been preparing for so long is over at last. But Sushma is no longer alive. She has taken her own life. Her last letter to Nandu asserts her belief that her destiny has always been in her own hands.

.jpg/img20210430_12464272%20(2)__570x480.jpg)

Ankahee is the second film directed by Amol Palekar, a well-known actor of the Marathi and Hindi stage in Bombay. A painter in his spare time, Palekar was working as a bank clerk when director Basu Chatterjee cast him in the role of an unheroic hero in his film Rajnigandha (1974). The film was an instant success, so was its unusual protagonist. Since then Palekar has acted as the lead player or in one of the principal roles in films like Shyam Benegal's Bhumika (1977), Basu Chatterjee's Chhotisi Baat (1975) and Baton Baton Mein (1979), Hrishikesh Mukherjee's Gol Maal (1979), Biplab Ray Chaudhuri's Ashray (1983), and Kumar Shahani's Tarang (1984). As in Ankahee, in his first film, Akriet, made in Marathi in 1981, Palekar probed into the tortured lives of individuals trapped by their own desires and their belief in supernatural powers.

Akriet was given the Special Jury Award at the Three Continents Festival at Nantes. ·

Speaking to Radha Rajadhyaksha in Movie, July 1984, Amol Palekar says:

Ankahee is based on a play, Kaalaaya Tasmaya Namaha, written by C.T. Khanolkar. Basically, it's emotional drama dealing with a human dilemma which has, fascinated me for long - the dilemma caused by the shades of grey in a man's character. I don't think many Hindi films have paid due importance to the fascinating possibilities of this problem-hung up as they have always been on simplistic, stark black and white characters.

Whilst casting for the film, I was very choosy. For each role; I wanted an actor who would fit it like a glove, who would live up to my conception of the screen character. Because as a director, I feel it is essential that you find the correct face and personality and not just pick any Tom, Dick and Harry.

Like, I couldn't think of any actress but Deepti Naval for the role of the 'subnormal' village girl. Deepti has that element of simplicity, that certain innocent charm which is very difficult to find nowadays. Similarly, for the role of my beloved, I needed a face which was non-glamorous and which reflected an inner strength. I had seen Devika Mukherjee in two Bangali films and I decided that she would suit the role to a T. For the role of Deepti's father, I approached Anil Chatterjee because of his basic warmth- the warmth that he radiates without saying a single word. In the film, he has to be rather harsh with Deepti, yet convey his feeling, his sympathy mutely. That's why I needed a great actor like him.

I have known Anilda for a long time now. He's extremely fond of me and jokingly calls himself my local guardian in Calcutta as I descend on him every time I visit the city. Initially, he was very sceptical about the Bombay film industry. When I first contacted him for the role, he didn't want to come here. Till I told him it was for a film I was directing. 'Oh in that case, there's no question of refusing,' he said. I was touched. After this film, I genuinely hope he does come to Bombay more often-such a fine actor should be exposed to bigger audiences.

Ankahee will be a turning point in Deepti's career-her performance in the film is one of the finest I have seen on the Indian screen. Before signing her on, I had heard a whole lot of stories about her-that she was moody, unpredictable, that she would give me date problems and so on and so forth .People went out of their way to warn me not to sign her. But I did. And not for a single moment have I regretted it. Deepti was co-operation personified and it was a pleasure working with her.

My playing the lead role myself was a matter of sheer convenience. Also there are, frankly speaking, very few actors who would be ready to accept this kind of role. The film industry being the place it is, people oversimplify matters and differentiate between 'positive' and 'negative' roles. For this reason, I didn't even approach anyone.

I have done a bit of unusual casting - I have Vinod Chopra, a director, playing the role of my friend. Vinod has a very interesting personality - a high-strung temperament which is at total variance with his babyish face. When he talks, you can see the passion emanating from every pore and that's exactly the kind of person I was looking for. In Ankahee, he plays my colleague whose wife has died as predicted by my father. He's supposed to be the silent, brooding type whose turmoil you can sense in spite of his continual withdrawal into himself.

Ankahee has four songs-all old bhajans. Khanolkar is one of the greatest poets in the Marathi language and it would be sacrilege to try and translate his work or get some film lyricist to write for the situations. The only thing we could do, was attempt to find parallels which are equally great and well-known. For one of these, the credit goes to my music director, Jaidev. There is a situation in the play, where the heroine sings about her tryst with death. We recited the poem to Jaidevji. He doesn't understand Marathi but once he got the essence, he recollected an old Kabir Bhajan, Kauno thagva nagariya lootal ho: This bhajan is very well-known in North India and it's the perfect parallel to Khanolkar's poem.

Asha Bhosle voiced the song Kauno thagava nagariya lutal ho in the film

Bhimsen Joshi happens to be very fond of me. I rang him up and told him I was coming to Pune to meet him but I refused to tell him why over the phone. 'Well, I'm coming to Bombay anyway next week for my concert,' he said, 'you can talk to me then.' No, I replied, I wouldn't like to disturb him at the concert. 'Come to the airport then,' he said.

On the appointed day I went to the airport. Bhimsen was there. Straightaway, I asked him, 'Will you sing for a film?' 'Is it your film?' he asked. I nodded. 'No, what I mean is, are you directing it?' Again the nod. 'Well, then there's no question of refusing,' he said and began to walk away. 'Hold on,' I said, 'let's discuss the other things too.' 'Ah yes', he said, stopping short, 'one very important question-who's the music director?' 'Jaidev,' I replied. 'Jaidev?' he repeated. 'In that case, there are no two ways about it. I must sing.'

Anyway, the recordings went off without a hitch. After every thing was over and it was time for Bhimsen to leave for Pune, he said to Jaidev, 'I hope I haven't disappointed you in any way.' Jaidev was almost in tears. 'How can you say this?' he asked. 'You have obliged me.' 'Not at all', countered Bhimsen, 'I am a fan of yours and I still remember many of your old songs.' He went on to list them and at this, Jaidev really broke down-this talented composer who has been so shabbily treated by the film industry could not control his tears at these compliments coming from a musical colossus like Bhimsen. It was a very touching scene. Even I had a lump in my throat.

I have an aversion to the zoom lens and avoid it like the plague. One of the reasons is that with this lens, things become so simplified that there's no fun left. And also because the use of the zoom lens has become extremely vulgarised-like slow motion in every ad film. I have not used it in even a single shot. In fact, Mangesh Desai remarked on it when he was mixing the film. Being familiar with the technicalities of film-making, he was amazed and also very happy that I had made another film without resorting to the zoom lens.

Not that I deliberately contrived complicated camera movement. It is the subject which determines what kind of treatment it should get. In Akriet, I had used static shots because the theme demanded that kind of blatancy. Everything- the lighting, the performances, the camera movement- had to be stark. In Ankahee, the movements had to be very dramatic to capture the tensions of the story. For example, a long shot slowly going into a close-up, with both the performer and the camera moving-this builds up a different kind of a tension.

During the making, we once found ourselves in a rather absurd situation. We were to shoot a night scene with Shreeram Lagoo and Dina Pathak, for which I needed the sea in the background. Here, the lighting was going to be the main hassle because we had used source lighting throughout. We could have shot on the beach with moonlight as the source but then, there was the problem of where to place, the lights. Apollo Bunder was a suitable site, but going through the bother of obtaining permission would have been too much. Then one day when I was passing the Mahim Causeway, I realised that this was the location and I could also get the reflection of the Mahim Causeway lights for that little extra touch. I was thrilled with my discovery .The next shooting day, we finished off our work in a nearby area and in the evening, my cameraman, Debu Deodhar, and I went ahead to Mahim Causeway to set up the shot.

We reached the place-only to discover that there was no water anywhere. The site was looking so rotten and mundane, I can't express it in words. Debu was shocked. I was so fazed that I couldn't speak. What could have gone wrong? Suddenly realization dawned. It was low tide, obviously there was no water around! Having little time at our disposal, Debu and I rushed all over the place to see if we could get our background some other place but to no avail. We had to pack up. The incident gave us such a jolt that immediately after that; the whole unit took to seriously studying tide patterns! Then we adjusted the tide to the schedule and a week later, finally took the shot at Mahim.

In fact, all the shots where we had anticipated difficulties were the ones we finished the quickest. The tough, one-shot scenes with lots of camera movement, which gave us a lot of problems theoretically were the ones we completed in a s1ngle take. I suppose it's because one's concentration is at its highest then.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema, 1986 issue. Images used in the feature are taken from the original article, Cinemaazi archive and the internet.

.jpg)