One of the-most consistent "cliches" we have borrowed from the American cinema is the emphasis and interpretation of the "romantic" element, connoting the emotion of love as presented in our films. Such love might be irrelevant, it might even be impossible, but it must be there.

Years ago Elmer Rice ridiculed the celluloid brand of "romance" where love was synonymous with starry skies (synthetically achieved), roses and Cadillacs (also synthetically contrived), "all of it garnished with a great deal of mawkish music and defying all the natural laws of space and time!"

Is it any wonder then, that so many saw no "romance" in the love of an ugly, sensitive girl for a butcher in "Marty"? And, yet, that was of the stuff of life itself, for how many heroes in reality sport the glamour of the "stars" of the celluloid firmament.

In the old days it was the rich man (gene rally a king) marrying, in the last saccharine reel, the impoverished but virtuous heroine which was the rage.

Today, perhaps symbolically of the change in times and social bias, it is the other way around. It is the villain (who, half-way through the film, threatens the heroine with the time-honoured "fate worse than death") who is rich. The hero generally is poor, shabbily attired, but roguishly charming, full of unrealised potentialities and beloved of the audience. The heroine's noble love for him is his salvation.

In the American cinema, love is the highest ideal- the love of a man for a woman, and vice versa. Such love is to be prized above all else. That frequently it manifests itself in a ludicrous manner does not alter its importance.

Exposed to this attitude, our film makers acquired certain definite overtones from it. The difference is that censorship regulations (which incidentally bear down heaviest on this score) are different as applied to the American cinema and ours, and the ways and means contrived to produce the same (or a similar) effect in our films are inevitably devious and an encouragement to include these more dubious elements in our films

One of the most patent devices is the love song-with a recurrent double-meaning in its apparently innocuous lyrical phrasing. It also accounts for much meaningless editing- the long vacuous close-ups suggestive of panting passion, as the camera scuttles from face to face like a frightened terrier; or the chase of hero and heroine through long-shot after long-shot across indifferent landscapes, or sinuous twining and twisting out of shrubbery in a manner reminiscent of animals with a predilection for trees. They are all part of the devices to cheat censorship.

A variant on this is the chase from sofa to settee and round teetering statuary in an over-furnished room decorated in glaringly bad taste. The fondling of bric-a-brac by hero and heroine is an obvious substitute for a genuine embrace; and all this is permitted because, thus disguised, it is assumed that the impact on the average mind will be less provocative than a straightforward kiss!

In actual fact, it is more than doubtful if this is so; for what the scene lacks in brief vividity is made up for by protracted suggestivity that appeals to the lower kinds of emotion of an indiscriminate audience, even if it bores the more intellectual. (Not to overlook the fact, that this is incidental incentive to irrelevant footage.)

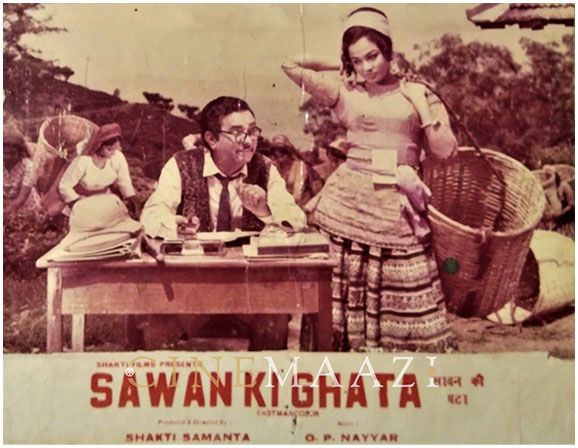

Then there is the element of "glamour," which must be superimposed to emphasise the appeal of "romance." In the finer films of the 'thirties, Indian costume and setting never seemed to militate against the atmosphere's being romantic or the various characters' falling in love. Today, however, the heroine must wear extravagantly hybrid clothes and the hero escort her through a number of insipid hybrid dances against impossible backgrounds.

Nor is there much plausibility in the characters and the situations in which they are involved. A star who has visibly aged continues to indulge in capers and banalities in imitation of the manner of his younger colleagues.

First, there was Devika Rani, and some of their early films, though they have dated a great deal, are regarded with affectionate indulgence in a haze of nostalgic memory. Ashok's next heroine was Mumtaz Shanti, followed by Leela Chitnis; of relatively recent vintage, one recalls the half-dozen -or-so films he made with Nalini Jaywant.

Some of the other famous pairs have since been re-snuffled. In the Dilip Kumar-Kamini Kaushal team Vyjayanthimala looks as if she is going to substitute. The throbbing intensity of the Raj Kapoor-Nargis starrers has now given way to a diluted version, with Raj Kapoor being teamed with diverse feminine leads, while the Dev Anand -Geeta Bali team, perhaps the best balanced of the lot, makes one miss some of the finer performances of Geeta Bali.

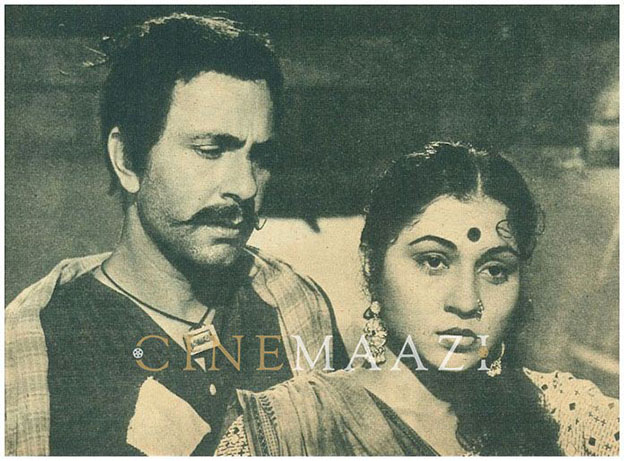

Nirupa Roy and Balraj Sahni are now be coming statically symbolic of peasant romance - and this is a pity, for both artistes have a versatility that could, one feels, be exploited equally successfully in other genres, such a comedy.

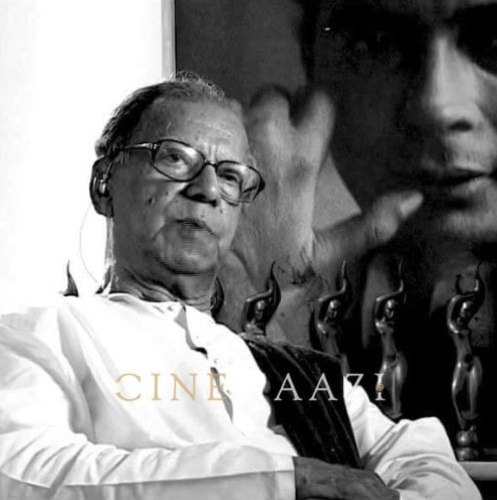

In Bengal, a similar state of affairs prevails. The logical successors to the Pramathesh Barua-Jamuna team are Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen (who have probably made more films together than any other pair). And the change in the brand of "romance" offered by the latter team is in keeping with the changed attitudes of the times. Even today, the films of the late Pramathesh Barua retain much of the sombre ate-ridden aura (most akin to the emotional intensity of certain French films) which was largely imposed on the film by Barua's personality.

And yet, when all is said and done, the fact still remains that this much-vaunted "romance" in our movies is essentially of a synthetic kind, like the rest of the cinematic elements in our films and that, though we have hundreds of "romantic" stories, there have come out of this not more than a handful of genuine "love" stories provoking the same degree of emotional response in the audience that, say, "Brief Encounter" did.

It is true that the genuine love story with integrity of emotion, finesse and honesty is perhaps the most difficult to make, but that is hardly justification for not attempting a more aesthetic and mature type of romantic film.

This article was published in Filmfare magazine’s September 22, 1961 edition written by Kobita Sarkar.

The images and captions appeared in the feature are taken from the original article.

About the Author

.jpg)