Holi: A Metaphor for Horizontal Violence

The Holi festival originated in pre-Vedic times as a spring festival involving a ritual sacrifice to ensure goods crops. The Vedic priests subsequently gave their sanction to the celebration, and in later times many myths were invented to give the ceremony a Brahminical orientation. In most of the myths the sacrificial fire burnt the forces of evil while the forces of good work rescued by divine intervention. The film Holi (1984) reverses the original myth. Here the sacrificial fire consumes the vital energies of our youth, after stifling their aspirations within the narrow confines of an unimaginative and regressive educational system.

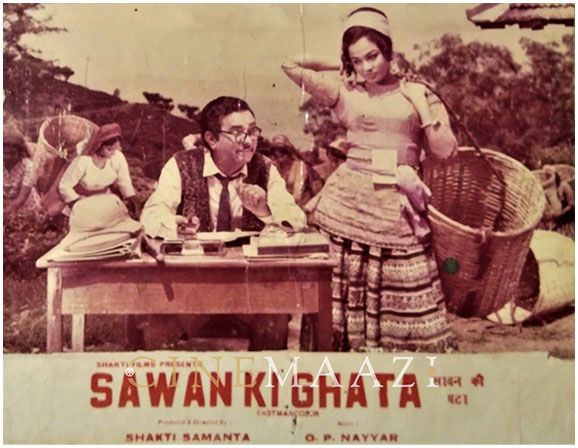

The college where the action takes place is one of many such colleges in the cities of India. The boys, especially the ones staying in the hostel, are a rowdy lot. Baiting the girl students is a daily pastime. But there is no malice in it and the girls usually ignore it philosophically or run when the going gets too rough. The teaching staff of the college suffer from the common apathy of most teaching staff in similar colleges. The administration has the usual problems--ill-paid employees who periodically go on strike to get their demands across. In fact, on the whole, the college is a very picture of normalcy. But the day is an unusual one. It is the day of the Holi celebrations, traditionally a holiday.

The boys in the hostel rise from their slumber, some from a night's drinking, heavy-lidded, or with a hangover, or just plain sick. Another night is over and there is no water in taps again. That is normal too. But on a holiday? The boys accept the temporary hardship stoically. Waiting for the water to come, they fool around, constantly on the move, each a bundle of concentrated energy. Then the news comes that the holiday had been cancelled. Instead there will be a lecture in the auditorium by the Chairman of the Board, on the cultural heritage of India. The boys decide to have a holiday all the same - they will not attend the classes.

The Principal, driving into the college in a chauffeur-driven car, is confronted by an irate and highly charged group of striking employees. One of them cheerfully lies down in front of the car and has to be dragged away by the guards. What a beginning to the day !

The classes are sparsely attended. The few who do attend, slip out of the class the moment the lecturer's back is turned. The new young woman lecturer is heckled so badly that she rushes out in tears. The hostel superintendent, the only lecturer with some human links with the students, watches the growing restlessness in the college. A notice announcing a further postponement of examinations adds to the rising bitterness. The Superintendent tries to warn the principal who is more concerned with the impending board meeting scheduled for the day. At the board meeting the Superintendent tries one last time, but the Chairman and founder of the college has only time to listen to his own voice. The young lecturer goes unheard.

The song is Na koi from the flm Holi (1984).

The news spreads like wildfire in the campus. The students feel that the decision is unjust. There are quarrels every day and a cut or two does not merit such a drastic punishment. The rebels gather with their crates of eggs and rotten tomatoes. Resistance is organized in the laboratory, in the library, in the classrooms and the college grounds. The students prepare for a confrontation in the auditorium. On neatly arranged chairs on the stage sit the Chairman and his wife with the principal. The student announcer is heckled and has to leave. The principal starts his speech in English and is at one shouted down. The Charman rises with a smile and takes his place near the microphone. He speaks with quiet condescension of his own rowdy college days, then moves on to the topic of tradition. A student rises and politely asks him the meaning of the word. As the chairman prepares for a lengthy reply the first egg finds its mark. A loyal employee holds up a trophy like a shield and escorts the Chairman and his wife to the car waiting outside, as bedlam erupts in the auditorium.

Seriously worried about his own job, the principal calls the hostel superintendent and demands to know the names of the students who organized the rebellion. The superintendent politely refuses any help. Staring out of his window, the principal spots one of the students on whom he may have a hold. He knows the boy's father. He is also not one of the popular boys in the colleges. He is a bit of a loner, unsuccessful socially or otherwise, occasionally the butt of jokes. The ideal material for the role of an informer.All the principal has to say is that he will tell his father what company the boy keeps.

The hostel superintendent unhappily announces the rustication of a large group of boys, all of whom belong to the hostel, including one who had nothing to do with the events in the auditorium as he was locked up in his room with a girl while it happened. 'Was it you who gave in our names?' asks one of the boys. 'No', says the superintendent, shaking his head sadly. The boys must vacate their rooms by the morning. Suddenly the boys are in a rage. They collect all the wooden furniture in the hostel and make a bonfire of them. They even throw in their textbooks in a final act of rejection.

The boy who gave the principal the names of the culprits can no longer keep silent.He admits to the boy he hates and fears most and whose name he has kept out of the list, that it is he who sealed the fate of his fellow students. His distorted sense of triumph is short-lived. The boys collect together and vent all their frustrations on him. The informer has his trousers pulled off, he is beaten, pushed around and abused mercilessly. Someone brings a sari to put round him, paints his lips and cheeks with lipstick. Someone else crops a path through his hair. He must dance, they demand, and the boy hops around in a grotesque fashion, terrified by the ugly mood of the crowd around him. No one wants to listen when one of the boys remonsteate that they torture has been taken far enough. The humiliated boy finally manages to rush away and lock himself in his room.

In the gathering dusk the boys sit listlessly on the steps of the hostel. 'What journey is this, where will the path lead?' They sing. The song fades into a depressed silence. Suddenly from the dar end of the verandah a boy shouts urgently, appealing, As they rush towards him, he is seen standing in front of the locked room, throwing up into the gutter below. The door is broken open and someone turns on the light and the fan. The danglisng object suddenly gains a shape and identify. The fan moves very slowly and hanging from it is the informer, dead.

The boys give their name, age and address to faceless policemen. Some are scared, some numbed into shock, some desperately pleading innocence. The night passes. In the first light of the morning the police van is seen carrying the boys away. Caught in the midst a rowdy, jostling crowd of merrymakers, playing with colours, the van edges its way forward relentlessly. The boys stare blankly, hopelessly out of the barred window at the shouting revellers. The van frees itself from the crowd and moves away. The camera moves to the tree tops as clouds of colour cover the screen.

We have tasted life here

We have tasted poison here

To mend a ton pocket

We have sewn our hearts here

The one who knows not himself is giving knowledge away

What journey is this, where does the path lead

The smoke rises

The home burns

At least save the city

O what is happening here

Let us go from there now, who will stay behind

What journey is this, where does the path lead?

We are not used to life

We have no time for death

There is only last wish

To witness the deluge

What kind of world is it, where will be going now

What journey is this, where does the path lead

Ketan Mehta was born in 1952 and graduated from St. Stephen's College, Delhi. He joined the Film and Television Institute ofIndia in Pune and revived diploma in film direction in 1975. During this time he directed a short feature called Madhya Surya, and a documentary film, Coolies at Bombay Central. After getting his diploma, Mehta worked for a year as a television producer in the Space Applications Centre in Ahmedabad during the Satellite Instructional Television Experiment. After a short involvement with the theatre, Mehta produced and directed a documentary, Experience India, for Air India. In 1980 came his first feature film, Bhavni Bhavai, produced by a co-operative which he formed with a few other graduates of the Film and Television Institute ofIndia. The film won two National Awards for the year: for the best art direction and for being the best film on national integration. It was also selected for the festival at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At home it received eight Gujarat State awards. The same year, at the Nantes Film Festival in France, Bhavni Bhavai was given the Unesco Club Human Rights Award. In 1983 Mehta produced a documentary for Gujarat Tourism, Tarnetar Fair, and directed and designed a play in Gujarati, called Channas. With Holi, his second feature film, he entered the field of technical innovation in cinema, innovation that he finds necessary in the present economic environment. Holi is made up of just 40 shots. 'Given the available technology,' he says, 'which allows considerable mobility in shooting, it is possible to design single shot mise-en-scenes lasting 8 to 10 minutes in duration. Given the sophisticated sync-recording equipment and multi-track magnetic mixing facilities, it is possible to do the entire shooting in sync. All it takes to evolve a structure of a full-length feature film comprising only these mise-en-scenes is a little courage, a little bit of imagination and a lot of hard work.' Thematically the film raises questions about the roots of violence and mass hysteria which can submerge the nationality of an entire group, and the validity of an educational system and social environment that ritually sacrifices the vital energies of the youth, suppresses the life-assertive urges by falling back upon a forgotten and obsolete culture, and leaves them without hope.

In an interview with Vijay Lele in Cinema India-International, October to December 1984, Ketan Mehta talks about his own hopes for the future of the cinema.

V.L.: This session is to grill you about your new film- Holi (Mehta parodies a shudder). Could you please sum up in just one sentence your experience in making this film?

K.M.: In once sentence? (Looks up form what he has been doing, viz., rolling a reefer. Smiles).All right. It's been one great trip, from beginning to end.

V.L.: Now to the gritty details. What made you pick up this particular topic-youth-as the subject of your film?

K.M.: Because, I think youth, collectively, is the most important, determinant factor in the future of a society. Too often, it's also the most susceptible target of the society's ailments.

.jpg/Pics%202(1)__400x480.jpg)

V.L.: Was the film inspired spontaneously from a stark confrontation?

K.M.: No. Bhavni Bhavai was like that, a logical result of my experiences while making films for ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation). The life and politics were an eye-opener. But the idea of making a film on youth has been a latent for a long time. In some way, for me, it's a going back in time..

V.L.: Going back to your college days in the radical sixties?

K.M.: That too, yes. I mean, the experience of Four guys actually leaving class to join a political underground movement was a rude shock to a gentle Gandhian-bred boy like me. But Holi really probes something else-the culture and psychology of youth.

V.L.: We have had filmdom's version-the hero more than the youth, fantasia more than real. As perhaps the first film from the 'Parallel Cinema' to probe the subject, what is the essence of your finding-your statement?

K.K.: Violence. I believe our present socio-political structure, and within it the educational system, is almost geared to breeding violence. That is even more true of the eighties than it was in the sixties.

V.L.: Isn't that tacitly providing a justification for violence among the youth?

K.M.: I am no judge to deliver judgment. I am trying to record what is patently visible. In the hierarchical top-bottom structure the end recipient is the youth. And there it takes a new form- explosions amongst themselves. In Holi, my attempt is just that- a metaphor for horizontal violence.

V.L.: In Elkunchwar's play, and later in the script, one of the climactic events is suicide. Doesn't it signify succumbing to oppression?

K.K.: It is suicide on a personal level. But, in fact, it is murder committed by society. The predicament is peculiar. On the one hand, the system inevitably goads them to repression, irritation, coarseness, violence. On the other hand, the perpetrators of violence become its own victims.

V.L.: Your film seeks to raise questions about this process?

K.M.: Yes.

V.L.: In as much as it does so, do you accept terms like new wave and 'Parallel Cinema'?

K.M.: Terms are important only if they help specify a reality; otherwise, it only breeds semantic squabbles.

V.L.: Let me put it this way. Do you sense a different cinema on the horizon-a cinema that has been steadily approaching?

K.M.: (Laughs) Yes... In fact, I think it isn't on the horizon; in many ways, it has already arrived. Without doubt, few countries have witnessed such an explosion of novel attempts in such a short span. There must be 50 such film-makers in India today. It's fantastic.

V.L.: Yet there are basic differences amongst them?

K.M.: Oh yes, undoubtedly. In theme, style, everything. For example, I may have serious questions about the appropriateness of Ardh Satya's (1983) end, or the attempt at epic form in Kumar Shahani's Tarang (1984). But for the creation of a mass culture of critical audience, the paramount need is to allow as many varied films of this genre as possible.

V.L.: What binds these films in common, then?

K.M.: I think, above all, they have initiated a process of looking at common place society, contemporary reality, with a perceptive, critical eye. Whether it's Kundan Shah's Jaane Bhi Do Yaro (1983), or Ashok Ahuja's Aadharshila (1982), or Sai Paranjpye's Sparsh (1980), it has caught the pulse.

V.L.: How has the mainstream cinema taken this-adaptation or resistance?

K.M.: A bit of both. I mean... take Meri Awaz Suno (1981) or Insaaf Ka Tarazu (1980), for instance. In spite of the justified criticism against both there is some change from the typical slotting of the 'unruffled cop' here or 'serves-woman-right' model. Of course, there is masala, bad ample doses of it, but there is also a bit of some lurking doubt.

V.L.: You also mentioned resistance by the film establishment. How?

K.M.: Well, in a variety of ways. Say,... take the distribution network. One can't forget that many of the films from the new cinema have been run as morning shows or matinees, not slated as the main attraction. A small example.

V.L.: Are you apprehensive about Holi?

K.M: No. We have some plans.

V.L.: No. I was't implying about distribution. I mean Holi seems to be a 'first' in many ways. For one, it's your first film in Hindi.

K.M.: Being in Hindi, it is more of an advantage. More reach.

V.L.: Why did you consciously choose new actors for the students' role? Wasn't that taking a risk?

K.M.: I wanted fresh faces. There is something special about the raw, explosive energy of teenagers. The tired professional collegians of filmdom won't do. The only known actors are Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri and Dr. Shreeram Lagoo-all making brief appearances.

V.L.: You are trying something very different, techniquewise, in Holi-live sound sync and long hand-shed shots. How do you feel about it?

K.M.: I'm quite excited about it.

V.L.: Both things can help reduce costs in some situations. Apart from that, you must have had a specific intention.

K.M.: Less expense wasn't the thing I had in mind. First and foremost, it is an experiment. An experiment specially tailored for the topic and structure of this film. The long hand-held shots and the live sound sync go hand in hand. (Smiles) In this case, that expression, hand in hand, is literally true. Anyway, the point is you can never quite re-create the mood, the tension, noises, the intonation, later in the dubbing room. This is all the more true when the cast is nonprofessional, which is as I wanted it. And in Holi, the camera moves freely, gyrating 360 degrees to capture the buzz, the whispers, the restlessness of a listless collective, all in one take. And the end effect, I think, is that the film achieves unbroken, greater and greater levels of intenseness... like Ravel's Bolero.

The article was originally published in Indian Cinema's 1984 issue. Images used in the feature are taken from the original article.

.jpg)