In 1957 the Communist Party was voted into power in Kerala in South India and it stayed the ruling party for a short period. In 1964 the Communist Party was split in two, the Communist Party of India and the Communist Party (Marxist) of India. Later many extremist splinter groups emerged. The first part of the film is set in the decade ending in 1955. The second part begins from 1965.

Truth, in philosophy, in politics, or even in the humdrum daily life of an individual, is never final. Between the image and the reality lies a vast chasm of uncertainty, an area of search. Who is Sreedharan? A firebrand revolutionary who has fallen upon bad times, a man in the throes of self-questioning and self-condemnation, or just a drunkard with a political past? In death, Sreedharan reverts back to the image that had led his people in a time of strife. But the living Sreedharan, the victim of an imperilled ideology, can provide no simple explanation of his personal reality.

The men and women who came close to Sreedharan during the days of his leadership, remember with reverence his simplicity, his austerity, his silent strength, his devotion to his ideals. He had a special relationship with the commonest, most insignificant of them. But at the same time he stood apart from them all, protecting his loneliness behind a wall of silence. Even young Sudhakaran, with his almost obsessive admiration for Sreedharan, and his close apprenticeship under him, could never penetrate the man's personal isolation. Savitri, who loved and desired him and bore him a son, can only recall her physical closeness to Sreedharan. His friends and compatriots of the trade union movement remember the stern idealist and his charismatic hold on the town's workers. But not one of them remembers Sreedharan as a complete human being. Sreedharan remains a phenomenon through years of political ambivalence that follow his disappearance, his reality submerged in the intangible abstraction of his image.

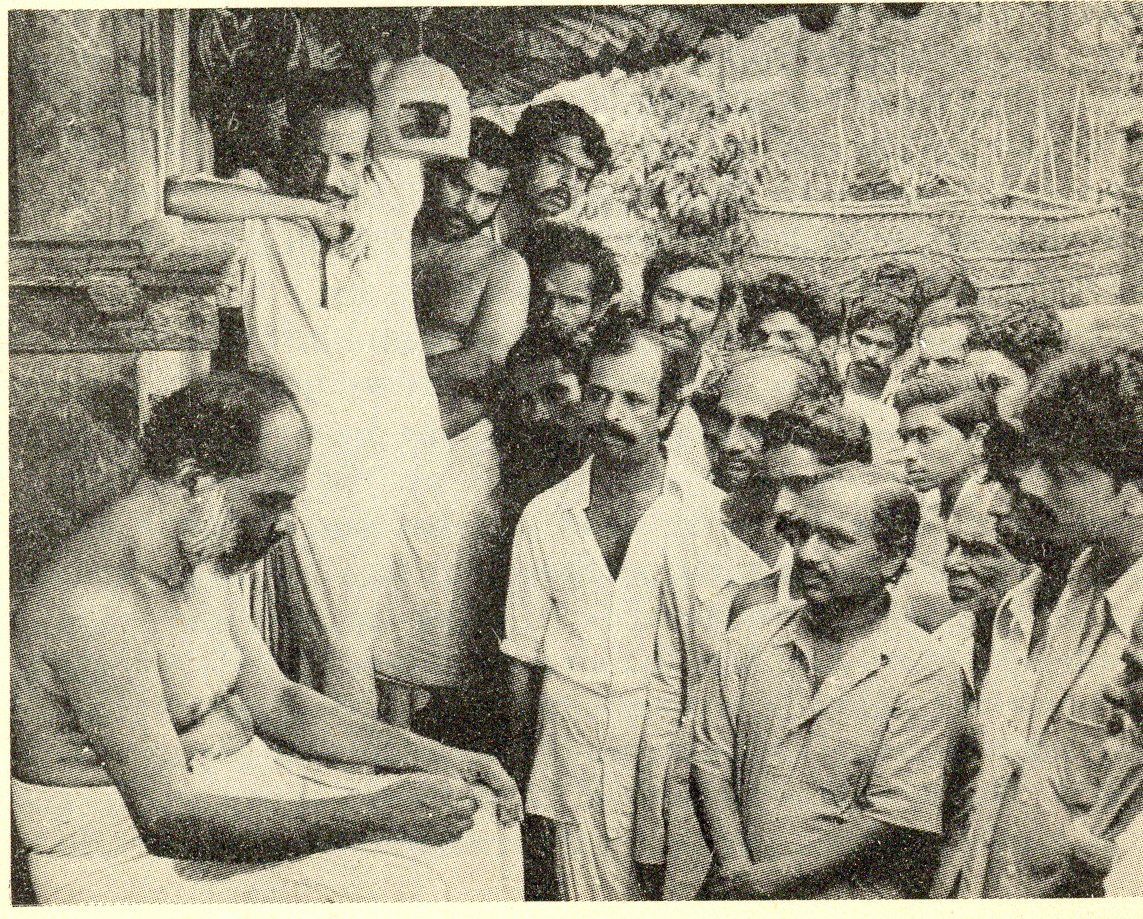

We first see Sreedharan with other leaders of the trade union movement, sitting in front of the gates of the tile factory. Mechanization in the factory threatens to take away the livelihood of the workers. Sreedharan leads the workers' agitation. A confrontation with the management leads to a prolonged strike. The party starts collecting funds as the workers' families face starvation. Sreedharan remains the key figure in the struggle for better wages for the workers. The man who runs the tea stall, the beedi shop owner, the common man in the street rally round his leadership. Young Sudhakaran listens to him avidly and schools himself in the intricacies of a political understanding.

One night an old farmer discovers Sreedharan lying bleeding on the ground after an attack by strangers in the dark. The farmer brings him to his own home where his daughter Savitri tends to his wounds. As he recovers, the forced physical closeness between them is transformed into a more intimate relationship. Sreedharan stays on in the old farmer's home, accepted as his son-in-law. But when the proprietor of the tile factory is found murdered, Sreedharan becomes the prime suspect. As the police start rounding up the leaders of the workers' agitation, Sreedharan and his comrades have to go underground.

Years pass, and Sreedharan's son, Sreeni, born soon after his disappearance, is now ten years old. In the intervening years Sreedharan's comrades have returned one by one and become involved in the changing face of left politics in the country. Sreedharan, believed to be dead, has become a legend and a permanent fount of inspiration. Sreeni, brought up on the memories of the father he has never seen, is the only one who actually awaits his return. And Sreedharan does come back. He steps into his home one night across the gulf of ten unknown years. He comes carrying ten years of exhaustion on his shoulders and promptly falls asleep. The news spreads and all the old faces crowd around the little house to have a glimpse of the man who has sustained them with his memory of steadfastness through the troubled years of his absence. All they see is a worn-out old familiar face, drooping in sleep. He has come a long way, he is tired. Poor man, let him sleep, they think.

As the days pass, Sreedharan slowly recovers from his somnolent state. But every day he drinks himself into a stupor and Sreeni finds him asleep when he leaves for school in the morning or when he comes back home at the end of the day. What used to be an occasional secret indulgence to dull the physical pain of a stomach ache, has become a daily necessity. Sreedharan is even willing to rifle his wife's meagre savings. Sreeni, suspected of being the thief, gets a beating from his mother. Later in the evening Sreedharan comes home blind drunk and the little purse he has stolen drops out of his pocket.

But it is difficult to dismiss Sreedharan as a common alcoholic. A legend come to life, Sreedharan is pulled in different directions by his old friends and admirers. The party has been torn into two. Rival aspirations have demolished ideological unity. The sustaining power of Sreedharan's old image leads the rival factions to vie with each other to use his name. Perhaps Sreedharan's alcoholism is a gut reaction to the destruction of a unified political identity that had formed the basis of his struggle in the old days. Between the ideological confusion and the personal political ambitions of his friends and admirers, Sreedharan dulls his pain with liquor. The ideal revolutionary becomes an embarrassment. Sreeni's friends throw stones at him. His old followers, the common people, mock him publicly. When the image, the abstraction that Sreedharan had stood for, is almost obliterated from people's minds, Sreedharan's body is found one day, beaten to death under mysterious circumstances. No one knows who killed him or why, no one wants to know. In death Sreedharan the idealist has returned to his people again. The rival parties parade the streets together resurrecting their hero. What was the image now becomes the reality. But who knows where the truth lies? Did Sreedharan betray the revolution, or did the revolution betray the man?

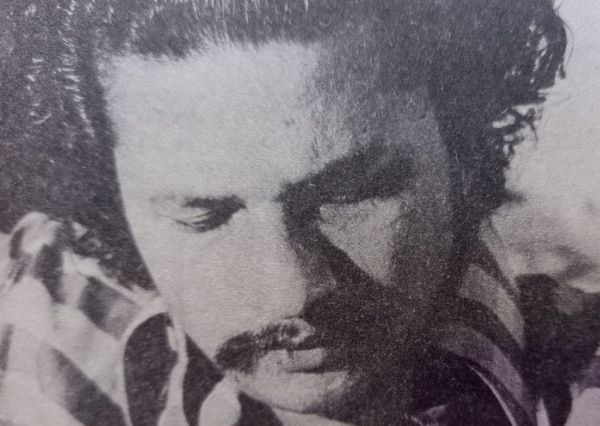

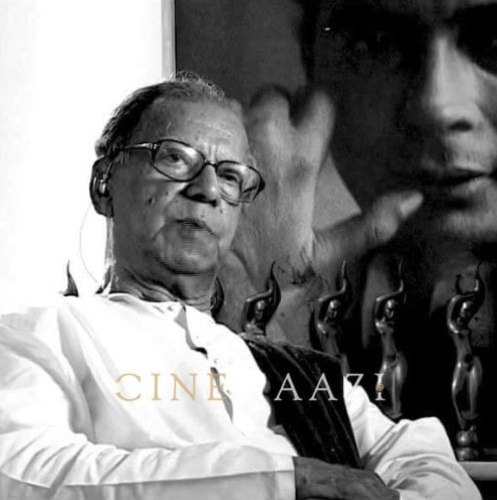

Adoor Gopalakrishnan was born in a small town of Kerala called Adoor. His family have been known for generations as patrons and practitioners of Kathakali, the highly stylized classical dance-drama of Kerala. Gopalakrishnan began acting on the stage at the age of eight. By the time he graduated from the Gandhigram Rural University in 1960, he had already produced over twenty critically acclaimed plays besides writing half a dozen of them himself. Recipient of a merit scholarship, he took his post-graduate diploma in scriptwriting and film direction from the Film and Television Institute of India in 1965. In the same year, he pioneered the film society movement in Kerala and founded Chitralekha, India's first film co-operative. His first feature film, Swayamvaram, made in 1972, won the National Awards for the best feature film, best director, best photographer and best actress. It also received the Kerala State Awards for the best film, best photography, best art direction and best music. His second film, Kodiyettam, was made in 1977 and won the National Award for the best regional film and the best actor. Elippathayam came in 1981, and received the National Awards for the best regional film and best sound recording. It was also given the Kerala State Awards for the best feature film, best photography and best sound recording. In 1982 Elippathayam received the British Film Institute Award for 'the most original and imaginative film' to be shown in the National Film Theatre that year. All of Gopalakrishnan's films have participated in various film festivals abroad, and won wide acclaim. Among his publications, Gopalakrishnan's book on the cinema, The World of Cinema, written in Malayalam, has won the National Award for the best book on the subject for the year 1983. He also received the Padmashree in 1983. Gopalakrishnan has scripted and directed, and occasionally photographed, audiographed and edited over twenty-five documentaries and shorts. Among them the most significant ones are The Myth (1967), And Man Created (1968), Guru Chengannur (1974), Yakshgana (1979), The Chola Heritage (1980), and Krishnanattam (1982)

Bikram Singh interviews Adoor Gopalakrishnan in the Sunday Observer, 2 December 1984.

B.S.: Do you think it is possible that some people may take your film as a rather sweeping criticism of leftist politics in Kerala?

A.G.: That's what some people in Bombay, especially Malayalees, have told me. But I do not consider it a political film at all. I am a serious student of cinema and I dare not call it a political film. A sympathetic viewing, understanding, that's what I expect of any serious viewer of my film. Basically the film is about my trying to understand the human mind its complexity.

B.G.: Your central character, Sreedharan, is something of a mystery. We see what may be called the breaking of Sreedharan, but there is little about his antecedents, about the making of the political person that is Sreedharan.

A.G. : He is a very dedicated Party man who belongs to the Communist Party in the decade before 1955. I am trying to understand him. In the film there are some reports about his possible involvement in the killing of a factory owner, but those reports are themselves contradictory. How do you pursue reality, that is the question. What is real, the image or the reality? I don't know for certain what Sreedharan did during those ten years, between 1955 and 1965, when he went underground. But I try to understand from what he does when he comes back. The questions asked in the film are genuine questions from the point of view of the common man—what happened to the spirit of such an idealistic ideology which gave us hopes and dreams?

B.S.: How far is the film based on real life events, personal experiences, like your last film Elippathayam was?

A.G.: I know characters like that, there are hundreds of them. The Party formally split in 1964, though the pulling apart had been there for some time. It is said that during that period there were many who took to alcohol, because they couldn't bear it, they couldn't understand what was happening.

B.S.: When Sreedharan takes brandy for the pain in the stomach, why does he want the fact to remain such a secret?

A.G.: There was a time when Party workers would do nothing that could tarnish the image of the Party—no alcohol, no womanizing, nothing that could be considered immoral. So, Sreedharan is an austere person. But in those days people used to work so devotedly for the Party, they would not eat properly, they would starve and develop stomach ailments. I have researched it—most of them had problems with the stomach, basically due to lack of food. And because they were underground they could not go to a doctor. So just to kill the pain they took alcohol. I have used it as a dramatic element. The second time he gets pain in the stomach it is when he meets his old colleague in the Party office where he listens to all that he talks, all platitudes, and when he comes out, there are these loudspeaker announcements of the splinter parties providing their interpretations of the current political situation. The stomach pain becomes at a spiritual level a pain that affects us ... So anybody who says that it is an anti-Marxist, anti-Communist film has absolutely not understood it.

B.S.: And you maintain that it is not a political film?

A.G.: I am not trying to preach this ideology or that. This is not an insider's view of things, this is not the view of somebody who is opposed to the ideology—it is neither. It is the view of somebody who is affected by the whole thing. Because Communism, I think, is the most noble philosophy that ever evolved on this earth. I am deeply affected by what happens to this ideology.

B.S.: The split is there not only in Kerala. Communism means different things to different followers in different parts of the world.

A.G.: Exactly. It is an international phenomenon. I am not talking about Kerala only, but I have to be specific and confine myself to things that I know.

B.S.: A noble philosophy generating so much confusion . . .

A.G.: I have quoted Lenin, through characters, throughout the film. The Marxist Party man quotes Lenin to the effect that at every new stage of the march of the proletariat some people will be unable to continue the journey and will drop out. This was very prophetic.

B.S.: With all these splits and branchings, the common man is confused.

A.G.: The common man is absolutely confused, no doubt about that ... The ideology got absorbed in smaller parties. Even the most reactionary parties raised the same slogans—Inquilab Zindabad. You cannot even tell who represents the left and who the right.

B.S.: Stylistically you must have had some problem while making Mukhamukham (1984) since you had to live up to the stature of the greatly acclaimed Elippathayam.

A.G.: Actually, any film of mine does not influence the next one. Because of the long intervals between my films I forget the earlier film.

B.S.: Going by one viewing of the film, you seem to have a very condensed, elliptical style of narration in Mukhamukham.

A.G.: Yes, I do not want the audience to just sit back and expect things to work out for them down to the last detail. I want them to participate in my search—when you are searching you cannot say things in a tone of finality. I do not want to do that. Secondly, the time of my audience is very precious. So everything that I show on the screen, every visual, every sound, every gesture, every movement that I use has to mean something, to build towards something. So this economy that I try to bring into the work, it necessarily means omission of the obvious . . . Personally, I have liked this film even better than Elippatbayam

B.S.: The sequence where Sreedharan comes back and people gradually flock to have a glimpse of him as if he were a creature from another planet seemed highly stylized ...

A.G.: You must see this film with the sounds properly heard. I used very ordinary sounds. A rooster crowing, to suggest early morning, is a very conventional thing, a cliche, and I have used it constantly to suggest mornings (laughs). The factory siren has been used for various purposes. The music used is the communist Internationale. The first time it is used is when the framed photograph of Lenin rises as it is put up on the wall. It is a very important sequence.

What is to be noted is Sreedharan's own face reflected in the glass—the two images merge. His own image rises in the same form at the end of the film to the accompaniment of the Communist Internationale played full scale. Even in the sequence of the raid on the party office where the picture of Lenin is pulled down and trampled upon, it is, first, the fall of the image, and then, its ascent, resurrection.

B.S.: You have said that this film has been with you as a concept for a long time.

A.G.: The first draft of the film was written at least two years before Elippathayam. Then after Elippathayam I rewrote the script. That makes the idea four years old, and it was shot one year ago.

The following is a note on Mukhamukham where Adoor Gopalakrishnan states his own artistic and political standpoint in the context of his film.

Mukhamukham is not really a total departure from what I have done earlier. My previous film, Elippathayam, dealt with an individual trapped in a situation which was mostly the making of a society in transition. In Mukhamukham, the society itself is caught in a crisis distraught by doubts, despair, inaction and remorse. It is a society that vaguely nurtures hopes about change but does nothing about it.

There lives a revolutionary—not necessarily political—in every individual. But in the course of time, as a matter of common experience, this spirit either dies out or becomes dormant. The idea of this film was born out of my desire to search for this spirit. Not being in the know of the final answers myself, I decided to give it a structure which is basically investigative in character.

At a point of time in the present, the image of a small-town revolutionary is progressively pieced together from reminiscences and statements of people who had known him and documents that related to his life and times. As an artiste who is sympathetic to the cause, I have logically filled up the gaps in the fabric of the story to construct an image that is real and credible.

The narrative returns to the same point of time and situation from where it started—to the present day society that is spiritually inept and morally corrupt.

Will this revolutionary, long absent from the scene, if called back and entreated, take up the challenge to shake the society out of its lethargy and slumber?

Driven by a sincere and deep felt desire to find answers to their questions, the people conjure up the man of the image from the past and wait listlessly for things to happen.

The man of the image turns out to be a bitter disappointment. He acts and behaves like themselves—withdrawn, indifferent, evasive, confused and even defeated. He cannot inspire them anymore.

He is in fact a projection of their own selves—a very inconvenient, embarrassing and menacing revelation.

Naturally they do not want to accept this for it is pointing the finger at themselves.

Soon the status quo is maintained by destroying the real and resurrecting the blemishless, venerable image of their ideal.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema 1984. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article and the internet.

.jpg)