"Saaransh Is A Film Close To My Heart." : Mahesh Bhatt

A point may come in the life of an individual when he must justify to himself his own existence, his reason for staying alive. A man who is daily losing control over his own life in a corrupt and brutalized environment is perhaps better off if he is out of this business of living altogether. Unless, of course, he can shift all responsibility onto the willing shoulders of an inscrutable god as Parvati has done: Parvati, wife of B.V. Pradhan, a retired headmaster, and mother of Ajay who was recently mugged and killed, quite senselessly, in a street in New York.

While Parvati sleeps, Pradhan wakes up, goes to his desk and starts writing a letter to his son. But Ajay is dead. Had he forgotten? Stirring in the cocoon of his grief, he remembers, and crumples the letter in his hand.

Day breaks and all the old habits take over. Life's business carries on inexorably around Pradhan and his wife. There are immediate problems that cannot wait. Now that Ajay is dead, the old couple must augment their meagre income by renting out Ajay's room to a paying guest. Sujata, a young struggling actress, comes to take the room. With her comes Vilas, her boyfriend and son of Gajanan Chitre, a municipal corporator who can bend everyone and everything to his wishes. Even Vilas is afraid of him.

Sujata, who is only waiting for the day when Vilas will marry her, has been trying to get him to speak to his father. But Vilas is too scared to even broach the subject. In the meanwhile both want Sujata to have a room of her own where Vilas can come and meet her secretly. As the young people take a look around, Pradhan gets a telegram and rushes out of the house. He has just received the news of the arrival of Ajay's belongings from America, and his ashes.

There is a long queue at the counter, of people waiting to receive gifts of colour television sets. Rejecting the offer of help from a tout, Pradhan waits in the queue for hours, only to be told that he must collect a few more papers from the right official quarters before he can collect all the goods. Pradhan tries to explain that he is only interested in receiving the urn carrying his son's ashes. But the harassed officer at the counter shouts at the old man. In desperation, Pradhan storms into the room of his senior who finally arranges for the urn to be delivered to him.

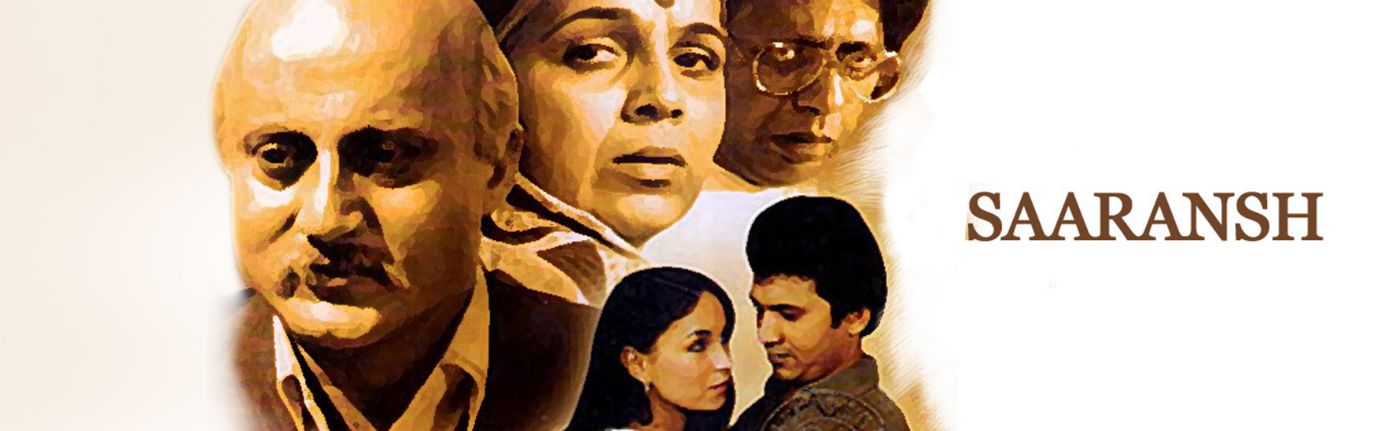

The trailer of Mahesh Bhatt's 1984 film Saaransh

In a valiant effort to continue living, Pradhan decides to look for a job again. He goes for an interview for a librarian's job but rejects the offer of the job so that it may be passed on to an old student of his who is obviously in a far more desperate situation financially. On his way home from the interview, Pradhan finds himself in the midst of a sudden riot. He is beaten up by a mob of youngsters, and manages to drag himself home late in the night. Overwhelmed by a sense of deep humiliation and unable to bear the finality of Ajay's death, Pradhan attempts to take his own life. He has no god who will save him from destruction. But Vilas, who has stolen into Sujata's room in the night, rushes out to help Parvati, and Pradhan is back among the living once more .

Shocked by Pradhan's suicide attempt, and frightened of being left alone, Parvati makes an offer to her husband. They will die together. At night, as the two old people prepare for their final escape, Vilas and Sujata have a quarrel. Sujata is pregnant. Vilas, who still hopes to win over his father before he marries Sujata, would rather get rid of the child. Sujata, outraged, and disgusted by Vilas's lack of courage in relation to his father, throws him out of her room. Pradhan and Parvati overhear the argument between the two. For Parvati, this is the message she has been waiting for. Sujata's child will be Ajay, reborn! She has no time to die now. For Pradhan too it is a moment of illumination. If Sujata wishes to have her child, Pradhan will help her; not for the sake of any blind belief in the guru's claims, but because it is Sujata's right to have her child that must be protected.

Pradhan begins by thinking that he will achieve what Vilas could not. He takes Sujata to Vilas's father. Gajanan Chitre, rich, powerful and uncouth, laughs at them, makes the trembling Vilas say that he has no responsibility towards Sujata and her child, and throws them out of his house. But the municipal elections are around the corner, and Chitre cannot afford to have the story of his son's indiscretion leak out to the opposition. Rallying all his forces together, Chitre attempts to persuade Sujata to have an abortion. A chain of events follows each one an incident of terror, forcing Pradhan, Parvati and Sujata into complete isolation. Parvati continues to protect the young girl with the passion of her faith. But for Pradhan, it is a battle against the annihilation of all human values. Pradhan is protecting all that he has held dear in the long years of his life; the right to individual freedom, the moral values that he has tried to inculcate in his students.

That he, a little man, does, after all, achieve victory, is really an accident of fate. That the minister he appeals to finally, turns out to be an ex-student, and manages with his magic wand of power to wipe out the nightmare, is one of those unprecedented and unbelievable happenings that take place more often in fiction than in real life. But Pradhan accepts it as an inevitable triumph over evil. Turning once more to the business of life, he decides to send Sujata away with Vilas who has finally rebelled against his father. It is his first step towards releasing Parvati from her obsession. Bereft of all emotional support, Parvati reminds her husband of their suicide pact. But Pradhan has learnt that one cannot die for the dead. As dawn breaks over the city, he takes his wife to the park where he had scattered a handful of his son's ashes. There, near a lonely park bench, the ashes have been transformed into wild flowers that stir gently with the breeze. Looking at the flowers, Pradhan and Parvati share a feeling of exultation, an understanding of the final assertion of life.

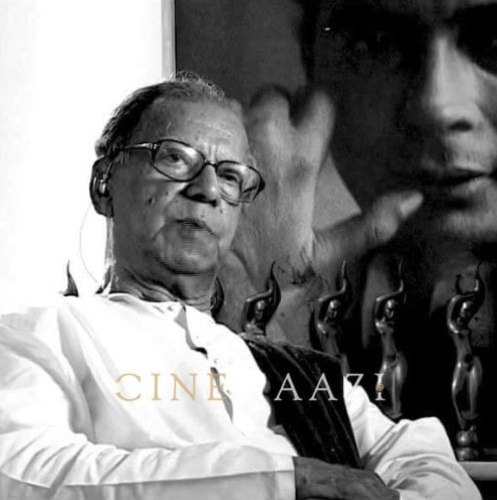

In an interview by Udaya Tara Nayar for Screen, 27 April, 1984, Mahesh Bhatt talks of his own experience with Saaransh (1984).

Born in Bombay in 1948, Mahesh Bhatt is the son of the well-known film-maker of yesteryear, Nanabhai Bhatt. His first directorial assignment was Manzilein Aur Bhi Hai in 1974, followed by Viswasghat (1977), Naya Daur (1978), Lahoo Ke Do Rang (1979) and the highly successful Arth (1982).

U.T .N.: How did Saaransh come about?

M.B.: Saaransh is a film close to my heart. After the success of-Arth, I really didn't know what to do. I had decided I wasn't going to gamble away my hard-won success by making just any film. It is not so difficult to attain success in this profession and in most cases of success the decline starts after the success, because success breeds insecurity that makes a man grab anything that comes his way to hold on to his success. I was careful to see that.it didn't happen to me.

I had this subject in my mind earlier but I hadn't developed it. Now after Arth I began giving it serious thought. The subject formed in my mind one evening when I was at U.G. Krishnamurthy's place. A woman came to him with a problem. She had lost her son and she wanted to know if he would be reincarnated, if she would be able to meet him somewhere in this life, if she, after her death, would be reunited with him. She was shattered and she was seeking solace in something that could keep her hopes alive, some assurance that could give her the desire to live her own life. I saw the torment on the woman's face, the turmoil she was experiencing within herself and I said, 'God, what's all this?' That was when I went home and thought about the finality of death and tucked away the seed of a subject in my mind.

Anupam Kher delivers an emotionally charged scene in Saaransh

U.T.N.: Any special reason why you took Anupam and Rohini to play the old couple?

M.B.: I had never seen any of Anupam's work on the stage. I had seen his photographs. That was all. Something about him told me that he was going to be ideal for the old retired headmaster of my film. He has done a marvellous job. You can see that for yourself when you see the film. Rohini is excellent, too. I donat have to tell you anything about her. In fact, the only thing I want to tell you is that I'd like you to write about my film and the wonderful people who have worked in it. The film needs to be promoted and they need exposure. Why bother about Mahesh Bhatt? No director, I can tell you is greater than his film.

U.T.N.: Didn't you think it was risky to make a film that questions our traditional belief in reincarnation and life after death and so on?

M.B.: I did. And I told my producers I was aware of the controversial nature of my subject but I had to make the film and make it my own way. There was no opposition, no interference from my producers. When you see the film you'll realize that nowhere in it have I said that death is the end of life. Life is a continuing process. The old man scatters his son's ashes in a children's park. Months later when he has a confrontation with his wife about life and death, he takes her to the park and shows her the place where he had sprinkled the ash and shows her the flowers that have blossomed there. She understands.

It is such subjects that fascinate me. Unless I feel intensely about a subject, unless it hits me deeply, gnaws at my heart, I cannot expect it to touch my audience. In the days of my failure, I sat and thought a great deal. I realised I could succeed only if I made my kind of films and not the kind of films that were in vogue. These days you know it is fashionable to attack corruption and expose social evils. But for Heaven's sake, who is interested?

U.T.N.: Do you draw from personal experiences when you are making a film?

M.B.: I do in the sense that images and memories stored away in my mind come up while I am visualizing a scene or a character and I use them. I've shot Saaransh in the lanes and parks I frequented in my childhood, which I spent in Shivaji Park. The house the couple lives in is a house I know very well. Similarly, there was always an image in my mind of a pregnant woman I had seen once with a dead child in her arms. It was a strange sight, a very disturbing sight, and I could never forget that image. It showed how life and death could co-exist in one person. There was life within her and death in her arms. That had set me thinking about life and death. The character of Soni becoming pregnant in this film is, perhaps, a derivation from that image in my mind. There was also my association with U.G. Krishnamurthy's son who died of cancer at the age of thirty-two.

He worked in an ad agency and was full of youth and creative energy. He died. He was in hospital and I watched him die. It was he who coined the 'happy days are here again' slogan. I saw death claiming a life which had so much left to accomplish.

U.T.N.: Would you never want to make a formula film, one with lots of dances and songs?

M.B.: I have nothing against those films. I have nothing against a Be-Aabroo (1983) or an Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). A big chunk of our film going population wants to see such films and enjoys such films. There is nothing wrong with it. What I am against are the Khandars (1983). That's supposed to be elite cinema. It is not for you and me. We have an elite cinema and an elite media to promote it.

No, I'd rather make something that I can feel close to and derive satisfaction from. If I've liked my own film, then I know that ten thousand other men are going to like it because they are as human as I am. In no way am I greater or superior to any one of the viewers who will be buying an admission ticket to see my film. If they don't like my film, then there is something wrong with me, not with them. All that a filmgoer wants is a good experience. Thank God for boredom, Tara. You and I are in this business because of boredom.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema's 1984 issue.

.jpg)