Diwakar Barve, a celebrated playwright and novelist, has been given a prestigious literary award. Mrs. Rane, a high society patron of the arts, is throwing a party in the evening in Barve's honour. Her guests are a mixed crowd of poets, writers, actors and intellectuals from different walks of life, all preparing themselves through the long day for the evening's festivities.

Who are these people? What are they really like in the hidden corners of their lives? There is Mrs. Rane, the rich widow, who has always projected herself to her children and friends as a genuinely sensitive, artistic person, misunderstood and neglected by a husband who had done nothing deserve her. To her daughter, Sona, who has produced an illegitimate child by a man she despises, Mrs. Rane is a parasite, sitting on a cultural vacuum, and living off the talent of people whom she pays with her patronage. Sona lives under sufferance in her mother's home, spending her days in silent rebellion against the frenetic social life around her, the false cultural mores, the desperate craving for recognition by little people, the arms outstretched for the gift of a foreign trip. Her emotional survival in a milieu she hates has been made possible only by her deep attachment to Amrit and all that he stands for, Amrit the poet-warrior, the ultimate romantic, who has gone over to other side of the battle lines to fight a losing war for the deprived and the dispossessed.

There is Diwakar Barve, the great writer, the keeper of the cultural conscience of the nation, respected, admired and emulated by a large number of younger writers. He alone knows that for years he has had nothing to say. He has repeated the same selling idea year after year, dressed in new clothes. What he has held up as profound has been hollow within. He has known how to survive, and has ruthlessly applied himself to that task. In the process, he has destroyed the one person who has genuinely believed in him and loved him-Mohini. Once a successful actress, the now-aging Mohini still waits for a single gesture of warmth from the man who has used her and rejected her long ago. Mohini has waited through the best years of her life for Barve to marry her. She gave up her career, the glamour and the adulation, to live with Barve as his mistress. Now she waits for his love, drowning her frustrations in drink, living in hope and in despair.

There is Bharat, the young rising poet from humble beginnings, wavering between the desire for the kind of success that Barve has achieved, and the remote, romantic dream of Amrit. There is Ravindra, the handsome, established stage actor whose soaring ambitions hide his secret desire of possessing Mohini. There is the grotesque middle-aged critic, Mrs. Abraham, hiding her advancing years behind a mask make-up, carrying around with her a reluctant youthful lover like a dog on a leash. There is the young leftist intellectual, Vrinda, quick to lash out at petit-bourgeois compromises, yet taken to belong to the privileged set who throng Mrs. Rane's drawing-room.

Behind the noise and laughter, the pretty quarrels and compromises, the party takes on a bizarre character of its own. Brief encounters emerge like small islands only to be swept away again. The shifting sands of conversation leave nothing tangible behind. But the But there is one latent force that holds each individual tied to his personal feeling of guilt-the name, Amrit. In his own way, each individual present at Mrs. Rane's party has been touched by Amrt's talent, and shamed by his passion for truth. Unknown to all of them, it has been also Amrit's day of reckoning. Amrit's friend, Avinash Kale, a young journalist, brings news of Amrit's betrayal. Amrit, bettered by the very forces he has been fighting against, lies injured in a prison hospital. Faced with the reality of physical suffering, the writers and artistes, the merchants of words, gather around in a free for all, where they are suddenly cornered, each one protecting his own attitudes, justifying his artistic stand, shielding his ambiguous position and intellectual role within the society that sustains him. As the evening draws to a close, news comes of Amrit's death in the hands of unknown assassins.

The ears leave one by one. The great house falls silent once again. Only Sona walks out of the house into the darkness outside to mourn Amrit and the passing away of a dream.

In Diwakar Barve's bedroom, Mohini lies in a drunken stupor, but Barve moves restlessly in his sleep. The battered and bleeding face of Amrit moves silently out of the darkness towards him.

Bharat sits awake in his room, haunted, like Barve, by the distorted, bloodied image of Amrit, his tongue pulled out of his mouth, his mighty voice silenced.

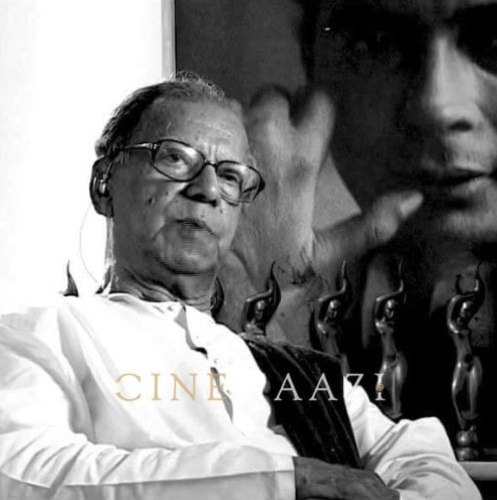

Born in the early forties, Govind Nihalani came to Udaipur as a refugee in 1947 from his original home in Karachi, in Pakistan. After completing his college education, Nihalani studied cinematography in Bangalore, at the S.J. Polytechnic. For ten years after that, he worked as an assistant cameraman for V.K. Murthy, the man behind some of Guru Dutt's best work. He then became assistant cameraman to director Pramod Chakravarty. Nihalani's entry into feature films was in 1970 when he photographed and co-produced Satyadev Dubey's Marathi film, Shantata! Court Chalu Abe. He has since photographed nearly all of Shyam Benegal's feature films, and for one of them, Junoon (1978), collected the National Award for best colour cinematography for the year 1979. His first feature film Aakrosh (1980) won the Golden Peacok at the 8th International Film Festival of India, held in Delhi in 1981. The same year, director Richard Attenborough signed Nihalani on as the second unit director-cinematographer of Gandhi (1982). Among his other films are Vijeta (1983) and Ardh Satya (1983). The latter proved to be a highly successful film, and won the National Award for the best Hindi film of the year.

In an interview with Lens Eye in The Times of India, 11, November 1984, Govind Nihalani talks about his two most recent films.

L.E.: Have you been accepted by the film industry after the commercial success of Ardh Satya?

G.N.: No. I don't think so. As far as acceptance by the film industry goes and especially by the distributors, I'm still judged on the basis of every new film I attempt. To the hardcore film people, I'm an unpredictable commodity. I trust the audience more than the film industry actually, I'm sure they will come to see what I've authored, they will be curious to see what Govind Nihalani's up to.

I agree Ardh Satya has become a kind of reference point for low-budget cinema-not so much for its quality or the issues it tackles but for thinking that such cinema can also be profitable at the box-office. I'm not too happy about this, a 'hit' usually means that compromises have been made by the director. I don't believe I made any.

L.E.: Why did you change the ending? Vijay Tendulkar's script closed on a more downbeat note, didn't it? Even in the case of your first film Aakrosh, you insisted on changing the end.

G.N.: What should matter is what comes off on the screen. In Ardh Satya Welinkar kills Rama Shetty. If you look at this superficially, then you can say, yes he gets his revenge. My intention was more complex: a man is trying to cling to his power, he refuses to be insulted and does the most drastic thing he can under the circumstances. He kills. Not only the end, but other points were modified as a result of discussions with Tendulkar.

As a film-maker, I should be given the benefit of the doubt; if I've changed something it's because I believe in it strongly. In the original version, which was also shot, Welinkar becomes an alcoholic, he is reduced to a vegetable. He meets Shetty, throws a glass at him and the next thing you know is that he has gone home and committed suicide. Sorry, but I'm not interested in this kind of a person. I'm just not interested in quitters. They may exist. The trouble is I'm only interested in those who take a stand, refuse to get cowed down, and don't know the meaning of the word 'submissive'.

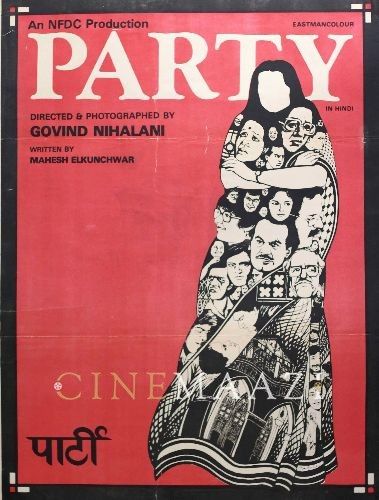

L.E.: Right. Can we walk about Party (1984) which you have just completed for the National Film Development Corporation?

G.N.: The film's based on the Marathi play Party by Mahesh Elkunchwar. He's a dear friend, I met him through theatre, through Satyadev Dubey actually. The play was performed on stage but I had heard unfavourable reports about the production, that Mahesh's view of Bombay society was amateurish and that his characterizations weren't deep enough. When I went to visit him at Nagpur (he stays there), he read out the play and I found it absolutely engrossing.

I thought here was a challenge: the play doesn't offer any changes in time, location or costume. A party is hosted for an award-winning writer, everything takes place on the same day and most of the action is concentrated in one set. There's no plot or the strong dramatic structure you find in my other films. On the other hand, there's a terrible amount of intensity; all the characters are placed in a claustrophobic situation. This has been rarely attempted by our cinema.

I've tried to achieve striking character studies. With each scene, a new aspect of a particular character is revealed. My aim has been to make the audience wonder whether each character is speaking the truth or putting on a mask. People, I feel, have to be shaded with ambiguity.

L.E.: How does the film differ from the play?

G.N.: There is a major difference in the thrust. The play's concerned with the question of art versus life. The film goes a bit further and tribes to see whether a person can have two contrary sets of morality. One as an artist and the other as a human being. My ultimate conclusion is that what you decide to do as a human is more important than anything else.

L.E.: How close have you been to this world of art, culture and parties?

G.N.: Fairly close. I don't look down on social gatherings, parties, whatever. Neither do I run after them. They can be uninteresting at times and stimulating at times. Just talking to someone, or listening to the general flow of conversation, or even observing the scene, can be a positive experience. In Party, you encounter all types. The film can also be viewed as a story of choices: someone might have chosen to become an activist while another person may have turned his face away from the rigors of commitment.

L.E.: Have you faced such a choice yourself?

G.N.: No. From the beginning, survival has been of the utmost importance. My family came from Karachi to Udaipur after the partition. We had to go through, tremendous financial crises. Father was trading in grain, he wasn't doing too well. By the time I went to study cinematography at Bangalore's S.J. Polytechnic, he had incurred heavy losses and the pressure was showing.

As soon as I finished the course, it was important for me to earn. I became the only earning member of the family. The situation is much the same today, a fairly large family has to be supported. Though, I must say the pressure has eased.

From the kind of subjects I've done, it's clear that I'm aware of the condition around us. Yet, I've never had the courage to leave, check it all up and get involved in fieldwork. But I refuse to take up the type of offers I've been getting from the industry. I prefer to make ad films for the money and develop subjects of my own choice. This is the only way I can remain in a position of strength.

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema 1984. The images used are taken from Cinemaazi archive, the original article and the video is sourced from the internet.

.jpg)