Women In Hindi Films : Dichotomy of Values

Some years ago, during a television interview with the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi, some of us raised the issue of the blatant debasement of women for pure sexual titillation in Raj Kapoor's block-buster, the commercial film, Ram Teri Ganga Maili (1985). When I happened to visit Bombay next, an otherwise quite likeable male colleague asked me with unconcealed hostility: "What is it that you people want exactly? Would you prefer there were no women in our films? Would you prefer it if they all wore long-sleeved khadi blouses and covered their heads? Why are you people against love and romance?"

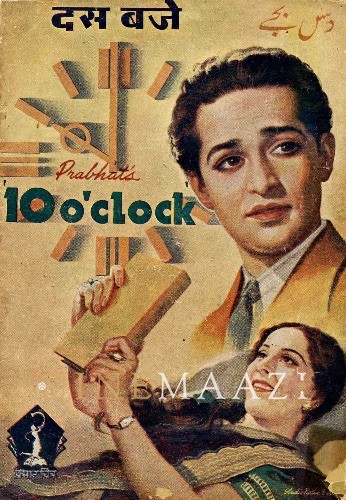

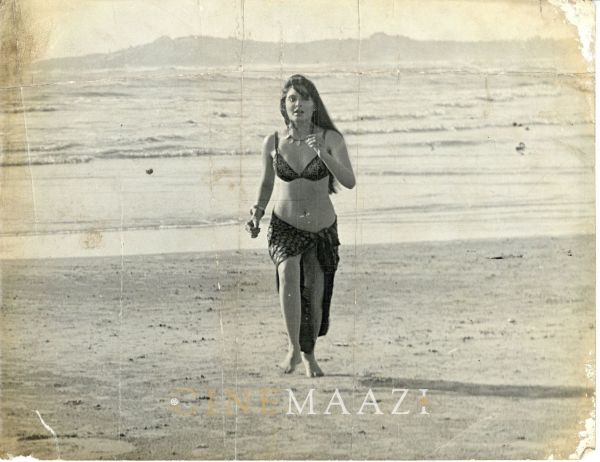

Today, a couple of years after Raj Kapoor's death, all sensitive film critics agree that the Great Showman's love sagas began to go downhill precisely as the shared erotic ethos of his films like Awara (1951) and Aan (1952) began to give way to the pornographic voyeurism of Sangam (1964) and Ram Teri Ganga Maili. Here, as man became the conqueror and woman the victim, the subtle warmth and mutuality of both in his earlier films were replaced by crude image of dominance and aggression. Such clear logic notwithstanding, one wonders whether the original misunderstanding has been cleared entirely.

Educated middle-class Indians, with their proverbial self-centredness often take an interest in people and events, not in order to understand and relate them to their own understanding of reality, but only to incorporate them into their own theoretical beliefs, just adding another chip to a personal mosaic as it were. Women, who raised the question about their misrepresentation in films with the Prime Minister may have merged in their minds with those women that they have read about (or think that they have read about), who burn bras and eat men for breakfast ! Women on the screen must similarly fit the mosaic labelled as this or that "type" or a particular director's concept of women. That the film actresses themselves, as women that they are and were, in life and screen, may remain almost unknown, elicits no surprise, not much anyway, even among the serious film-critics.

Lives and careers of successful film actresses from Goharjan to Dimple Kapadia, steadily disprove (what the films, along with textbooks, elders, teachers, parents and grand-parents, have long been telling women) that the name and security that "homemakers" enjoy, shall be denied to women, who wish to create a life outside the private domestic one and those that walk out of a marriage shall live to regret it evermore. But, this is seldom, if ever, revealed, although film journals, even in the 1950s had revealed that women, like Nargis, Madhubala, and Begum Para (the highest paid vamp in her time) easily put the lie to those ancient fears about female capacity for "financial independence." Emphasis is always laid on their sorrows and vulnerabilities, never on their joyous victories and strength of character. Actually, well-to-do women are dangerously easy for us Indians to resent and put down. Even women film-journalists have been guilty of a kind of reverse snobbery here. Independence that comes to strong women is not seen as their just due, but as something of a luxury justifiable vis a vis women in good economic terms, when jobs for all sexes are aplenty. That all these women have worked for their causes, money, and fame, the same as men do, is a thought generally discarded because it does not fit the traditional mosaic of the Indian female.

Neither are the women in show-biz, who've come from humbler backgrounds like Rekha, Rakhi, Mumtaz or those who have had to work since childhood for simple survival, like Sarika and Neetu Singh are seen as standing on the frontier of asserting the right to work for all Women of all classes. Their ambition and guts, should have been seen as their strategies for survival but film-journals usually end up bitching about them.

Actually the film world in Bombay, like the political world, is a reflection of a very Indian dichotomy of values. On the one hand, both the politicians and the film-makers must pander to a restless irreverant and youthful audience. On the other, they must constantly re-affirm traditional values and prejudices that sustain and support the basic structure. Female stars are under pressure to subscribe to this hypocrisy. One discovers, in interview after interview, even those actresses, who are known to have been destroyed by bad affairs, sponging on male-relatives and leech-like avaricious mothers, keep on underscoring the absolute sanctity of virginity and maternal and matrimonial bonds. Even when one gutsier-than normal actress among them (like Rekha or Dimple or Pooja Bedi does an "Uncle Tom") she does it with subtlety and a certain self-deprecatory humour! It makes sense!

The status quo within the film-world protects itself by punishing all challenges; particularly those, whose rebellion hits at what is the most fundamental social organization; the family. In fact, there seems to be no punishment that equals the viciousness and ridicule, that males within this industry reserve for women who rebel against their macho social mores.

Even arty and liberated film-makers like Mahesh Bhatt are not above asking for the scalp of the women, who has sinned. The Kapoor clan's aversion for bahus and betis stepping into the family business is legendary, and marriage for a Pooja Bedi still means coping with art, films and Kamasutra ads. But come to think of it, if intelligent actresses like Pooja Bedi worry about marriage and having babies, how and when and who with to settle down should it not be understandable? Have you ever visited a campus, where young girls and women teachers are not similarly worrying about some aspect of combining a normal married life with a career? About not just being a "good" woman, but also seen as being one?

In films, photographs and books, our actresses have mainly been seen through a male prism. If we discard it before going through their lives, we will be struck immediately by the same mysterious lack of professional discipline, self-pride and confidence in the most successful of our actresses; as in our women writers, scientists, and professional managers. Given the above attitudes, it is not surprising. The men, on whose goodwill and recognition all working women have mostly had to be pathetically dependent, wish women to be vulnerable. They, in fact, often make female vulnerability the basic requisite for granting of favours. Women in all spheres, therefore, face similar pressures. And, this is why brilliant girls, who scrape past colleges and interview boards, also do not have more confidence, than these women who have to parade past beauty-contest judges, leering financiers and lecherous film-producers many, many times. A really perceptive socio-psychological analysis of these haunted and haunting daughters of Venus, has yet to be presented.

This article was originally published in Indian Panorama 1994. The images used for the feature are taken from the Cinemaazi archive and the interent, they were not part of the original article.

About the Author

.jpg)