The Social Role of the Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

One of the more serious purposes to which the cinema was put early in its career was as commentator on the social scene and arbiter in its problems. This was done in several countries with varying degrees of success, and one every so often there is resurgence, often conscious, of the trend.

The social purpose of the cinema might originally have been stimulated by a quest for a higher morality, but the two functions are quite distinct.

While the cinema's purpose of defining morality to the exclusion of all else has debatable value, social intent can, on the whole, added serious purpose to the cinema, if intelligently exploited.

Some of the finest films in many countries have been made on these themes, but it is not sufficient to assume that, just because a film is informed with social purpose, its other shortcomings cane be overlooked.

The Russians were the first to recognise the vast potential of the cinema as a medium for influencing the general outlook and to use it consistently as such. If the result gave their cinema a rather one-sided development, he exceptionally good films which came out of this attitude are perhaps some justification for it.

In the American cinema, a social attitude tends to invade all genres of the cinema - not excepting even the "western" - and the social role of the cinema has often been used to very good purpose.

The gangster cycle, with obvious elements of popular appeal, was perhaps the first concentrated American effort at social realism. Since then various cycles (generally more violent) have predominated.

The crime wave of the 'thirties was exposed in such masterpieces as "Scarface" and "Angles With Dirty Faces," and after the war the famous semi-documentary tradition, encouraged doubtless by the Italians, was among the most worthwhile contributions of the American cinema.

Violence in other spheres - racial relations and local prejudice - also became a theme, and more recently, in an effort to combat evils like dipsomania and drug addiction, a series of films, "I'll Cry Tomorrow," "The Man With The Golden Arm," etc., have been made.

Films of this type used once to be conceived on the impersonal "thriller" principle. Now, the evils are emphasised by their application to a personal sphere - to people who exist or have existed in actual fact.

The handicap of it is obvious and the films fail in social responsibility because of the obvious concessions to sentiment which have to be made, so that often the issue is clouded by incidental considerations. Where, however, such considerations do not prevail, the impact is more effective.

Even in an avowed western like "High Noon," there is an oblique reference to the local conscience, for it raises the question of the individual's responsibility to the community in a common emergency

Again, in a number of films, Kazan has given a very personal interpretation to the problems of contemporary existence. Handicapped largely by censorship restrictions, he has been unable always to give a decisive solution and has had to resort to the intelligent compromise.

In a sense the realistic purpose of these films was more significant, for they dwelt on problems which are part of every man's experience. Crime, violence and mob fury, undoubtedly important factors, refer to humanity under stress.

Again, while Russia has used the cinema to further a political ideology, he French, despite the handicap of severe political censorship, has managed a more intellectual appreciation of some of the more radical social problems.

"We Are All Assassins" was a powerful plea for the abolition of capital punishment and "He Who Must Die" pitted local ambition and apathy against visitor humanitarian considerations - without any pandering to a smug audience.

The recent "Les Tricherus" exposed the cult of frenzied living that is threatening to ruin the younger generation. Perhaps, it is in reality the problem of only a small, restless minority - but it is an influence which might well become a universal menace.

It is an interesting paradox of American censorship that, though it is on the whole stricter on matters of sex, there is a surprising broad-mindedness in the matter of social self-criticism, for no other country could have given such frightening picture of its young hoodlums - as in "The Wild Ones," for instance.

The French, compelled to restrict their social problems to being reflected incidentally through powerful themes of emotional intensity, do not come anywhere near the honesty of the Americans, while the Italians, buck to the more sensational problems of the realism, propound very exciting but not very honest cinema.

The Japanese, for their part, deal with the more sordid problems (currently sex) but not always with a degree of subtlety.

Yugoslavia's "H-8..." was a novel experiment designed to enlist the people's sympathy and assistance for police routine.

In this one sphere, the Indian film has bravely, if not effectively, made its own contribution. That it has done so with a lack of discrimination and monotonous moralising does not detract from the sincerity of its attempts.

There are two distinct ways of going about things when exposing the shortcomings of the social order. On is to make a powerful film, without obvious reference, but with an implicit bias which makes the film's sympathies self-evident, as many of the Italians did; the other is to take a problem in its starkness, build a morality lay round it, and drive home the lesson with sledge-hammer persistence, till the most dim-witted member of the audience is aware of the point at issue.

In Italian cinema, the classic example of the expository tirade is Rossellini's "Europe '51." Despite its excellent theme, it had long moments of crass banality derived from this weakness. It failed miserably.

This is the method, too, of the Indian film.

Aspects of the social order are reflected as a series of social problems. They are examined in the glare of a searchlight and magnified as under a microscope. Lengthy traders are then projected at the audience. It is presumed that exaggeration, over-emphasis and persistence carry greater conviction than merely a sincere statement.

It is perhaps a fact, that the latter form of exposition is more suitable in countries where a large percentage of the population is not unduly enlightened, and for whom the lesson has to be crystal-clear and emphasised with force.

But the question is: is this audience in a position to eradicate the evil?

If the problem is not a question of mobilising the public conscience, but something, say, in the line of legislation, does it not rest with the more intelligent and influential section of the audience to remedy it? This being so, should not the appeal be made to them?

Indian films have long dealt with problems in a romantically "realistic" manner and their purpose is eventually defeated because of pessimistic resignation particularly in the case of women, perennially ill-treated and helpless.

The actual exposition is at times very strong, especially in the case of social problems created by economic or traditional sanction. For instance, many of the films based on the novels of Sarat Chandra Chatterjee reflect the problems of the original, outmoded in a changing world but retaining interest for reasons of literally familiarity. "Barididi", "Devdas" and "Biraj Bahu" are notable examples.

The same consideration also applies to the many other films adapted from the classics.

But there is Shantaram, conspicuous for at least a couple of decades for his development of social themes with a degree of success.

His accent, however, is inevitably on the heavy side, and films like "Duniya Na Mane," whose social purpose makes it an important film in an evaluation of the cinema in India, seem in consequence more dated.

His more recent effort, "Teen Batti Char Rasta", a plea for provincial goodwill and harmony, has some remarkably deft and telling touches on the other than. They do not fail to make their mark.

Another well-known Indian director, seriously preoccupied with social lls till recently, was Mehboob.

His classics in this tradition are "Roti," concerned with economic inequalities, solved rather in the fashion of Utopia but an important film nevertheless; "Andaz" and "Fashion", these two containing lengthy fulminations against modern society; an "Mother India," depicting a hapless victimised peasantry which presumably has never heard of co-operative farming or agricultural progress in general.

Of relatively early vintage is "Sindoor," a film still interesting for its story value and its reflection of social prejudice but whose social purpose is a bit out-dated. This is also the case with the more recent "Ek Hi Raasta."

An unheralded, unpretentious film which showed a greater appreciation of current difficulties is "Talaq," made with a relatively little-known cast. It centres itself on the problem of divorce which has come into prominence recently.

"Sujata," another recent film o caste prejudice, is a well-meant anachronism, ad "Seema," a film on juvenile delinquency, also solves problems in a fanciful rather than a factual manner. It is otherwise an admirable film.

While most of these films mainly deal with the conventions of society, films made by Raj Kapoor reflect economic uncertainties and inequalities. They probably prove more effective, because they manage to disguise the deeper lesson with surface attractions, such as the charming rogue, the central figure of the film, who symbolises the ideal of frustrated romantic youth.

"Shree 420," perhaps, epitomises this creed, though "Boot Polish," despite its long tirades flung into the auditorium from reel after reel, rather after the pattern of the song formula of other films, was a far more purposive film and it remains a pity that audiences did not take more kindly to it.

"Jagte Raho," also in a serious vein, was perhaps less successful than it might have been, because he lesson was not so obviously diluted. As a venture in social realism, it was a noteworthy effort.

"Naya Duar" was the first of a series of films which focussed attention on the contemporary theme of the Five Year Plans. It has been disputed as to whether the message was, or was not, reactionary and the film must be given credit for trying to say something, in addition to being reasonably good entertainment. Not all subsequent films were as good - but implicit in them as a new interest.

The provincial cinema has also made its valuable contribution to social realism, although that realism often has an even more restricted application. The Marathi "Shyamchi Aai" was a noble effort for it rose above the limitations of purely local terms to achieve universal application.

"Ora Thake Odhare," a Bengali film, made a humorous plea for the mutual adjustment demanded by congested living conditions resulting from Partition.

The main trouble with most of these problem films is that, instead of casually reflecting the social scene so that the audience can come to its own conclusions from what transpires and instead of repeating this till it becomes part of the unconscious thinking of the audience, the evil is emphasised and exaggerated so that it is grossly out of proportion and its impact reduced to a farcical point.

Is it because a produce deciding on a serious theme finds the "problem film" a facile solution to his task? More often than not, the theme he chooses is antiquated. It has not contemporary point and even less contemporary interest and pungency. But is has the treat asset of being so neutral, that no susceptibilities are likely to be offended.

A general indictment of the social and economic inequalities of the national scene is one thing; an exaggerated, untrue contrast is another. And why not make films to create in the average mind, a live and vital interest in current developments in planning and reconstruction and constructive thought upon issues which may be controversial today and which will be history tomorrow, instead of passing off for them the burning problems of grand-mother's day as if they are of profound consequence today?

There is not much point in appealing to the die-hard prejudices of social minorities, for the chances of their accepting the lesson imparted by a films are small, indeed, if they have remained uninfluenced by the life around them.

The general absence of social realism in the Indian cinema reflects a strange immaturity of thought. Objective interpretation of the current social set-up is likely to produce greater understanding than lengthy diatribes against national and social evils.

This article was published in Filmfare magazine’s 25 September, 1959 edition written by Kobita Sarkar.

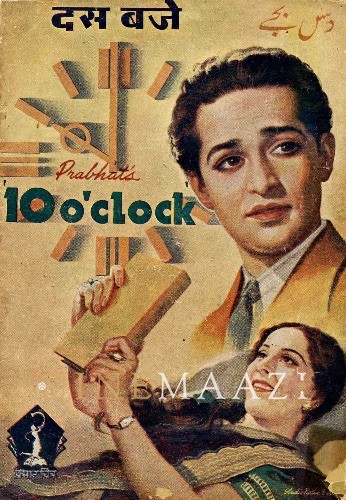

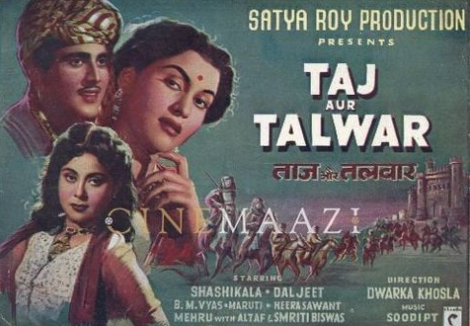

The images appeared in this feature are from the original article.

.jpg)