The Growth of The Motion Picture

Shadow plays were common in India centuries ago, but the motion pictures came here from the West and provided a happy blending of the dramatic and photographic arts. It was only on the 7th July 1896 that the Lumiere Bros. held the first cinema show in a room at the Watson's Hotel, now Esplanade Mansions, in Bombay. The show was attended by about 200 persons after paying Rs. 2/- each. The first show outside the hotel was given on 14th July 1896 at the Novelty Theatre, now known as Excelsior Cinema, in Bombay. There were two shows a day and each was of about 12 pictures. The rate of admission ranged from 25 nP for the gallery to Rs. 2/- for Orchestra Stall and Dress Circle. It also led to the first cinema advertisement in India on 7th July 1896 in the Times of India as, "The Marvel of the Century, The Wonder of the World, Animated Photographic Pictures, Life-size Productions."

Signor Colonello and Cornaglia (Italians) continued giving successful cinema shows in Bombay during 1897 and 1898, and were followed by others like Messrs P.B. Mehta, who opened his cinema 'America-India', J.N. Tata, who installed a cinema apparatus for private use at his residence. Some Europeans, Clifton and Company (Photographers) and Mr. P.A. Stewart also started cinema shows at various places in Bombay. These were, however, all casual shows and the regular film shows were only started at Bombay in 1904 by M.D. Sethana with his Touring Cinema Company. In 1907, Mr. Pathe also continued regular cinema shows and the growing public patronage gave the impetus to many others to start cinema shows in other parts of the country. It was by 1910 that cinema halls had sprung up in all the important places in the country and continued to exhibit the English films till the birth of the Indian motion picture.

Raja Harishchander (1913) was the first Indian film of 3,700 feet long, which took seven months and twenty seven days in the making. It was born out of the Indian soil and labour and was produced by D.G. Phalke, and proved to be a great success when released in regular shows on 17th May 1913 at the Coronation Theatre in Bombay. It was a significant coincidence that at the same time the full-length feature film Queen Elizabeth was also released on the Western screen.

The great success and the increasing popularity of the motion pictures led the Government to pass the first Act known as the Indian Cinematograph Act of 1918, and it, of course, with amendments, remains the most important Act affecting the film industry till today. This Act empowered the Provincial Governments to make their own rules in regard to :- 1. For the regulation of cinematograph exhibitions for securing public safety. 2. For examining and certifying films as suitable for public exhibition. 3. For carrying out the general provisions of the Act. The Entertainment Tax was also introduced in 1922 in Bengal and in 1923 in Bombay.

In 1921, the feature films Bhishma Pratigna was produced by the Star of the East Film Company in South India. In 1924, the Great Eastern Film Corporation was formed in Punjab and the Light of Asia was released in 1925. It was a great achievement, as this feature film was based on the life of Gautama Buddha and was produced with the co-operation of a German film company named 'Emelka' of Munich. The film was jointly directed by Himanshu Rai and Franz Osten. The Indian investment was Rs. 90,000 and the rest of the capital was foreign. It had its London premiere in 1926 at the Philharmonic Hall and remained in continuous exhibition for over ten months getting the honour of being the third best picture of the year out of a poll conducted by the Daily Express.The great Eastern Film Corporation got only two prints of the picture out of 425 prints to recover the Indian investment. The Corporation failed in 1928, as their feature film The Love of a Moghul Prince was banned by the Board of Censors, which had been established in 1920 in some Provinces, and also for the reason that this film could not stand the competition with Anarkali (1928) of the Imperial Film Company of Bombay.

The important role of the cinema in the economic and social life of the people led the Government to appoint an Enquiry Committee in September 1927, known as the Indian Cinematograph Enquiry Committee of 1927, to examine the position of the film industry. The Government, however, could not take any action on its report.

From 1913 to 1930 about 45 producing companies came into existence, but in 1927-28 only 21 concerns were existing and, out of these some 9 concerns were keeping a steady output of pictures. In the year 1927, there was only one company which had an average annual output of 15 feature films and about 5 companies had an annual output of 10 to 12 features films. The total number of feature films produced in the country, however, was on the increase every year.

Cinema houses also were established rapidly during these years. Total number of cinema houses existing in the country, excluding Burma, was 122 in 1921, 251 in 1927, 346 in 1928 and 390 in 1930, besides, of course, some touring cinemas. These cinema houses, however, were not sufficient in number for the existing population at that time. In other countries, the number of cinema houses was much larger, as in 1930 the U.S.A. had 20,500 cinemas i.e. one cinema for every 5,857 people, England had 3,700 cinemas i.e. one cinema for every 12,740 people, while our country had only 390 cinemas i.e. one cinema for every 974,049 people.

Studios came into existence near about 1920, when artificial light began to be used for making the motion pictures, but the studios continued to be in primitive stage till 1930, even though they numbered as many as 22. These studios were attached with the Developing, Printing and Editing rooms and comprised mainly of area walls with glass or wooden framework with curtains to diffuse the light. Persons working in them were not real experts except, of course, a few, who had some training of a desultory character. The salaries of the technicians were not high. Film-stars worked on monthly payments ranging from Rs. 30 to Rs. 800 per month. The average cost of a feature film was between RS. 15,000 to R.s 25,000.

As people in the early days were fed on religion, complete era of mythological films existed upto 1920. Then came the era of Rajput legends followed by stunts and afterwards by socials. Thus, these successive stages improved the technique of the Indian films no doubt, yet it was far below that of foreign films which were imported and distributed by four major concerns. The distribution of Indian films was mostly undertaken by the producers themselves.

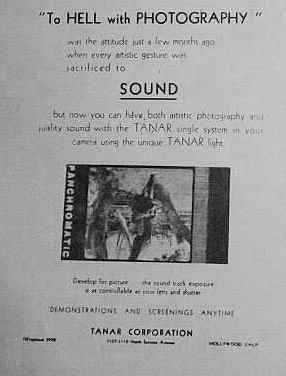

The period from 1931 to 1935 was one of transition. While the first talkie named Melody of Love of Universal's was shown in the country in 1929 at the Elphinstone Picture Palace, Calcutta, the talkie era in the country dawned only on the 14th March 1931, when the first Indian talkie feature film Alam Ara, produced and directed by A.M. Irani, featuring Master Vithal and Zubeida in main roles, was released at the Majestic Cinema in Bombay. As in the West, the introduction of sound brought improvement in almost every branch of film making in the country. The initial cost of equipping studios and cinema houses for the sound was taken up with a new zeal, as the persons believed that the talkie was to provide more profits and stability to the film industry. The rise in the cost of production of feature films from Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 125,000 could not disturb the producers on account of increasing box-office collections from about Rs. 2 lakhs in 1913 to Rs. 1 crore in 1931.

While some organisations came into existence in 1929, it was not till 1932 that the Motion Picture Society of India was formed, which consolidated the organizational side of the film industry. In 1934, the Motion Picture Society of India was registered and it organized the first all India Motion Picture Convention in Bombay on 20th February 1935 and passed four important resolutions.

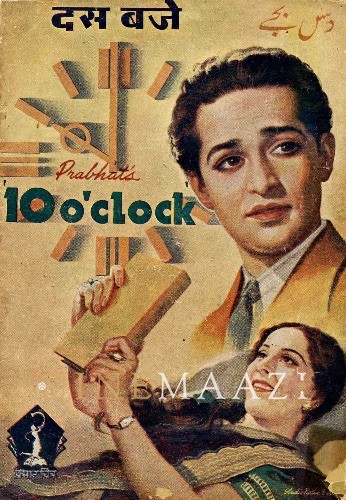

The period from 1930 to 1935 marked the birth of producing concerns like Messers Ranjit Movietone. Wadia Movietone, Bombay Talkies, Parkash Pictures, Prabhat Film Company and New Theatres Limited. Film production showed a constant increase and reached a point in 1935 which could not be surpassed until the latter half of 1947. Besides the feature films like Chandidas (1934), Devdas (1935), Bharat-ki-Beti (1935) etc., one Cartoon film also came out on 25th November 1935. Sound films became common all over the country by the end of 1935, and silent films were neither produced nor imported after this. The monthly salaries of the film-stars ranged from Rs. 100 to Rs. 1,500. In this interview, the film-star Nawab said that he got Rs. 1,400 in 1933 for his role in Yahudi Ki Ladki (1933) of New Theatres Limited and that it was considered a princely sum at that time.

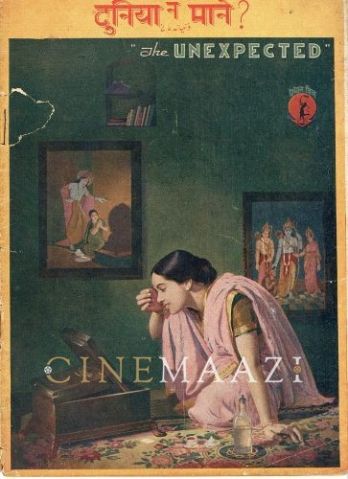

The period from 1935 to 1939 was one of consolidation. Film-journalism, which so far was hardly in vogue also became common. While 'Filmindia' became very popular and remained exclusively a film magazine, the 'Times of India' also started devoting special columns to film-news and reviews of the films, and the Motion Picture Society of India too brought out its journal. This growth of film journalism helped the film industry to establish a direct link with the public on the one hand, and the Government on the other. Though lesser feature films were being produced during this period, the quality of most of the feature films was high, and pictures like Achhut Kanya (1936), Sant Tukaram (1936),Amar Jyoti (1936), Duniya Na Mane (1937), Kisan Kanya (1937) and Mother India (1938) etc. proved to be classics of the time. Two feature films Kisan Kanya and Mother India ware made in colour and the latter film proved quite successful. Further attempts in producing colour films, however, could not continue owing to high production costs and lack of production facilities. Out of the two feature films, Amar Jyoti and Sant Tukaram were sent for the Fifth International Exhibition of Cinematograph Art, Venice, on 10th August 1937. Sant Tukaram was declared among the three best pictures of the world. And, for the first time in the annals of the motion picture, and Indian feature film came into limelight.

The number of cinema houses also increased from 700 in 1935 to 1,265 in 1039 and new cinemas like Regal, Eros and Metro were gradually brought into existence in Bombay. American film magnates too started occupying cinemas for exclusive exhibition of their pictures, and the permission granted to the Metor-Goldwyin Mayor to erect a cinema caused much resentment in the film industry. In the words of the President of Motion Picture Society of India, "This venture will not merely be in competition with the indigenous exhibitors but generally and definitely tend to be a monopoly of exhibiting all super American productions......the proposed American venture constitutes a serious menace to the Indian film industry." However, the plans of America to capture the Indian market for films in a wholesale manner could not materialize, for it was shelved with the outbreak of World War II.

The Second All India Motion Picture Convention was held at Madras towards the end of 1936. The film industry enjoyed its Silver Jubilee celebrations in Bombay from 28th April to 18th May 1939. The Indian Motion Picture Congress was held on 7th and 8th May 1939. Side by side with Congress were also held the Indian Film Journalists' Conference on 30th April, the Indian Educational Film Conference on 2nd May, the Indian Distributors' and Exhibitors' Conference on 3rd Maya and the All India Cine Technicians and Artists' Conference on 4th May 1939. These conferences though could not help in the solution of the main issues involved, but they set the pace for organized unity in the film industry for the times to come.

The Motion Picture Industry of India, on its twenty-fifth birthday, occupied 8th place among the Indian industries and 4th place among the film industries of the world, turning out 9% of the total world production of the feature films, while America was the top and Japan turned out 27th%, U.K. 22% and Germany 7%.

The period from 1939 to 1945 was of the Second World War. Though the war did not spread on the Indian soil, yet the country felt the shortage of raw materials. The inflationary tendencies in the country increased the prices tremendously. The inflationary boom provided a better scope for employment and made easy flow of money possible. As a result, the cost of production of the feature films went up four times and the collections at the box-office increased three times. No doubt, the film industry enjoyed some sort of economic prosperity, but it was wiped off to a large extent by increase in costs and taxation.

The inflationary boom brough about 130 producing concerns and increased the number of studios to 50. But there was a fall in film production by 48% by the end of 1945 in spite of several new-comers in the field of film production. The exhibitors, in many cases, found it difficult to run the cinemas due to heavy taxation, and, as a result, the number of cinemas was reduced from 1,265 in 1939 to 1,136 in 1941. Some of the exhibitors also went into liquidation. The exhibitors, on the whole, however, secured better returns on each film at the box-office and the distributors started charging rentals as high as 70% of the gross collections. As the public had easy money, the number of picture-goers tremendously increased and the black market in cinema tickets started in spite of the best efforts of the Government and the cinema managements to stop it. The increased taxation, on the other hand, created the practice of the receipts and payments in the film industry in 'Black' to avoid the payment of the taxes and it is effective till today.

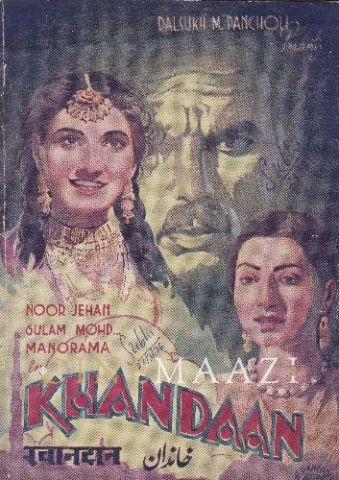

Many of the features films produced during the period enjoyed good collections at the box-office, and the following feature films are noted for their unprecedented collections in the years in which they were released as noted against each: Kangan (1939), Pukar (1939), The Only Way (1939), Aurat (1940), Bandhan (1940), Punar Milan (1940), Chitralekha (1941), Khazanchi (1941), Padosi(1941), Basant (1942), Bharat Milap (1942), Roti (1942), Khandan (1942), Kismet (1943), Prithvi Vallabha (1943), Ram Rajya (1943), Shakuntala (1943), Tansen (1943), Taqdeer (1943). The feature film Curt Dancer produced off the track with English Dialogue by Wadia Movietone in 1941 could not get success in and outside the country owing to its incongruous English dialogue.

The Directorate Military Training inaugrated the Indian Services Film Unit known as 'Combined Kinematograph Services Training and Film Production Centre' in 1941. This unit made films in 35mm and 16mm size. It was disbanded in June 1947. It, however, made about 300 films in 14 languages during its short existence, and the number could not be surpassed by any other similar unit in the world. Thus, for India it was an achievement and a record to be proud of.

World War II ended in September 1945. The control on the distribution of raw-films was lifted on 15th December 1945, and production of trailers up to a length of 300 feet was permitted. The withdrawal of the Defence of India Rules on 30th September 1946, put an end to all the restrictions imposed on the film industry during the war period. The anti-climax of the post-war period, however, cannot be appreciated without taking into account the division of the country on 15th August 1947, communal disturbances immediately after it and then the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi on 30th January 1948, as all these events had their serious repercussions on the film industry.

The inflationary boom of the war period made the film industry somewhat prosperous financially and, therefore, it attracted a number of new-comers to the production field. It led to an enormous increase in the production activities within two years after the war, which could only be surpassed in 1955. The business methods of the newcomers were most unscrupulous. The unexpected rise in production activities created scarcity of raw-films and shortage of studio space, talented technicians and artists. It all resulted indirectly in an increase in the costs of the materials and made the rates of interest mere exorbitant. Besides, a heavy increase system of 'freelancing' also started. The virtual ban on the construction of new cinema houses made the shortage of the exhibition facilities more acute in the country.

The Cinematograph (Amendment) Act of 1949 made the Censorship more strict from 1st September 1949 enforcing 'A' and 'U' certificates for the feature films. The Entertainment Tax was also increased. The Films Division of the Government of India was again revived in February 1948. Exhibition of approved films was once again enforced by laying down a condition in the licence of the exhibitions in June 1949, that they would exhibit approved films and pay rentals for them.

To sum up the position, the Second World War ended when the film industry was enjoying the inflationary boom. War time profits gave way to the new-comers, encouraged competition of feature films to unexpected heights, reduced the profits per picture and made the cost of production very high. This led the producers to cut down the expenses. In consequence, the standard and quality of the pictures naturally deteriorated. Ill-equipped and unprepared for a change in its fortune, this business proved to be a gamble and remained so till today.

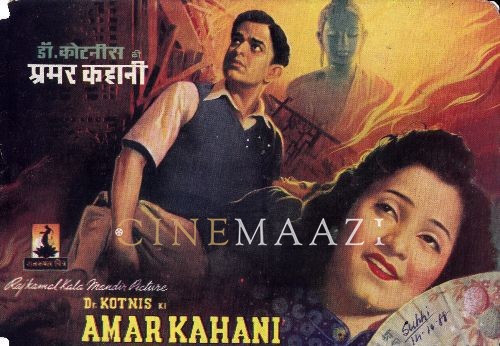

During this period many feature films produced in the country also faired well in other countries. In 1946, Shri V. Shantaram conducted a deal for the distribution of his three feature films Parbat Pe Apna Dera, The Story of Dr. Kotnis and Shakuntala in the U.S.A. and Canada. The pictures were dubbed in English and Shakuntala was released on 4th January 1948 at the Art Theatre, New York. It remained in exhibition for about two weeks. Chetan Anand's feature film Neecha Nagar (1946) won 'Grand Prix' at the World Film Festival at Cannes in October 1946 and was placed among the four films selected out of 47 films by the International Federation of Film Journalists. Story of Dr. Kotnis, Ram Rajya (1943) and Shah Jehan (1946) were selected for exhibition by the Government of India at the Canadian National Exhibition held in August 1947 at Toronto. Dharti Ke Lal (1946) was released in the U.S.S.R. for the first time. Kalpana (1948) got prize at the Second World Festival of Film and Fine Arts at Brussels in June-July 1949 for its technical qualities. Other feature films exhibited in International Festivals in 1949 were Meera (1947), Chanderlakha (1948) and Chhota Bhai (1949).

The years 1950 and 1951 were of confusion and dismay for the film industry. The recommendations of the Film Enquiry Committee, submitted to the Government in October 1951, could not be implemented due to the pre-occupation of the Government in development projects and other problems of greater importance. The movement of Children Films was started in 1952. Towards the end of 1953, the film industry lost its second position and was pushed back to the third position among the film producing countries in the world.

The reasons for this fundamental truth is that the Indian film industry developed mostly under the laissez-faire system except, of course, during World War II when some controls were enforced. The absence of planning, both careful and proper much reliance on individualism rather than on collective efforts, too little regard for art and an undue stress on cheap entertainment values, the presence of misfits and unfits in key positions, heavy taxation lace of organization and co-operation, strange hold of finance, the absence of any clear-cut policy in regard to direction, purpose and regulation on the part of the Government, the multiplicity of controlling authorities, dependence on the foreign markets for raw-materials and competition from outside, have all affected the film industry in its progress on sound lines. Reluctance on the part of the film industry to accept what it owes to itself and to the public has also retarded healthy development.

This article was written by Rikhab Das Jain and was a part of Film Industry of India, compiled by B K Adarsh in 1963. The images used in the feature are from Cineplot and Cinemaazi archive and was not part of the original article.

.jpg)