Tarang (1984) presents a saga of conflict and betrayal stretching across the boundaries of different worlds. The industrial empire of Rahul's father-in-law has the seeds of dissension within itself. At another level, the working class outside confronts the industrial establishment. While political manoeuvrings bring about a parting of ways within the working class, a clash of divergent ambitions leads to the disintegration of the industrialist family. Finally the real world gives way to the mythical, where all polarities may converge without contradiction to give birth to a new hope for the future, where the exploited and the exploiter can move towards a common destination.

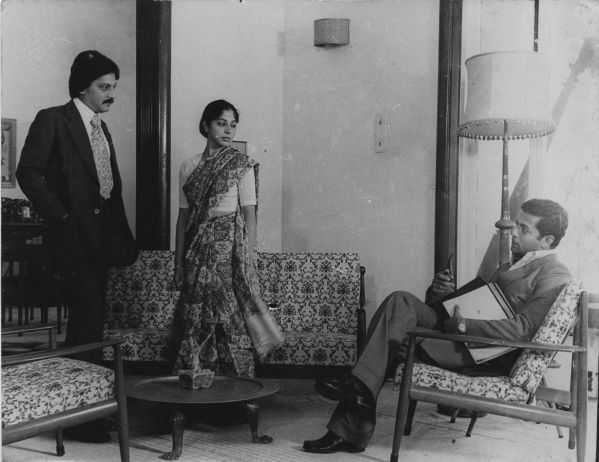

Rahul, the son-in-law of the old Seth, is locked in combat with Dinesh, the Seth's nephew, on the matter of running the old man's industrial empire. Dinesh believes in unscrupulous methods that will finally bring him an additional income. For Rahul, indigenous production provides him with a cover of fashionable liberalism to conceal his personal ambitions. In the centre of the conflict sits the old Seth, a bit bewildered, his own sole concern being still the old-fashioned one of amassing wealth for the family. The Seth's daughter, Hansa, sits on the sidelines and watches with growing anxiety the effect of the conflict on her father, the only man she has ever completely loved.

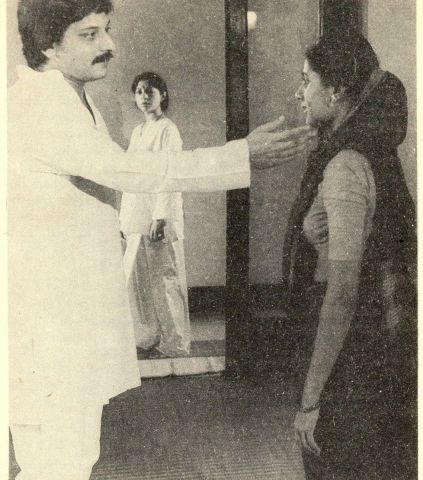

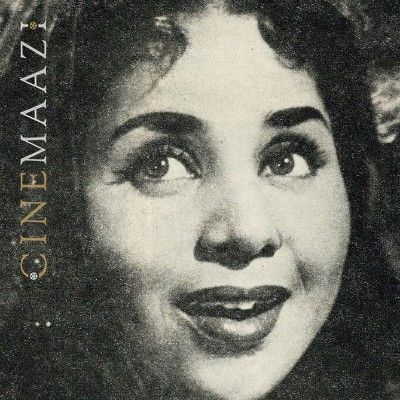

Janaki belongs to the world outside, the world of shanty towns where the workers in the Seth's factory eke out their existence. Her dead husband had once led the workers against the management, and she herself is still considered potentially dangerous because of the respect and affection she commands among the workers. Thrown out of her shack by the Seth's henchmen, Janaki is picked up from the streets by Rahul and installed in his palatial home, ostensibly to look after his child. For Janaki, Rahul has always been a champion of the workers, and working for him she may even be in a better position to help her old friends. As Janaki grows in self-confidence and becomes increasingly indispensable, Hansa willingly withdraws from her husband's life, pushing Janaki into a relationship with Rahul. Hansa, whose sole obsession is her father, believes that she has done her duty by producing a son and heir for the vast family fortunes. She persistently repulses Rahul who still feels strongly physically attracted by her.

Janaki's role within the family becomes more ambiguous when the old Seth falls ill. Rahul, who has reached a point in his career where he can do without the old man, insists on keeping Hansa away from her father on the pretext that it would only upset her finely tuned sensibilities. As Hansa moves around like a ghost, waiting for the blow to fall, Janaki, under Rahul's instructions, befriends the nurse and takes her away to her own room at the slightest opportunity. Here she plies the nurse with drinks, a secret weakness that she has taken pains to discover, while the sick old man lies alone, neglected. On one of these occasions, the nurse comes back to find the old man dead.

Dinesh comes back from one of his sojourns abroad and accuses Rahul of actually killing the old man. But the Seth's death is shrouded in mystery and nothing can be proved against Rahul. Rahul has in the meantime consolidated his position by setting up his designer friend Rusi and marrying him off to Anita, an old paramour of Rahul's and the old Seth's trusted secretary. With Anita's help, Rahul humiliates Dinesh's foreign collaborators and puts him in a false position. With the help of Janaki and the workers he also effectively removes Dinesh's local ally, a crooked self-server and trade union leader who had ingratiated his way into the old Seth's confidence, and instigated a communal riot among the workers.

Meanwhile there is a rift in the ranks of the workers and Janaki's closest friend and old admirer, Abdul, is on the run. Rahul sends Janaki away with the child to a bungalow far away in the hills where they are supposed to stay till the problems arising out of the Seth's death are solved. But Rahul has other ideas. On the one hand, he successfully buys the allegiance of one section of the workers and the leadership, on the other, he comes to Janaki and tells her in no uncertain terms that she is to be accused of the old man's death. Janaki's betrayal is complete. She packs her few belongings and walks back to her old life. In Rahul's home Hansa moves in a dream, hugging to herself her last possession—her grief for her dead father. As far as she is concerned, it is the strife between her husband and Dinesh that has killed her father. Yet left without her father's protection she tries one last time to rouse herself and respond to her husband's needs. After a long time she makes love to Rahul, and wakes up next morning with promises of a more fulfilling relationship. But by the evening she is dead, lying submerged in the bathtub. The last link in the chain snaps with Rahul arranging for the murder of Dinesh's business associate in such a way that the blame will fall on Dinesh. Rahul is now free to run his empire according to his own rules. Janaki has taken refuge with an old friend, Namdev, who is also on the run from his erstwhile comrades. As Janaki waits for him to come back home one day, somebody throws a lighted cracker in the room. Janaki runs out as the row of shacks goes up in flames. The dissolution has reached her doorstep once more and driven her to the wilderness outside. The film ends on a conjectural-mythical note when in a dreamlike sequence, on a long, lonely bridge, Rahul approaches Janaki once again with the offer of a life of freedom and equality. Janaki, now a mystical abstraction, rejects the offer with divine indifference. Go back to your destiny, she says. I am like the first light of the sun. I am as hard to catch as the wind...

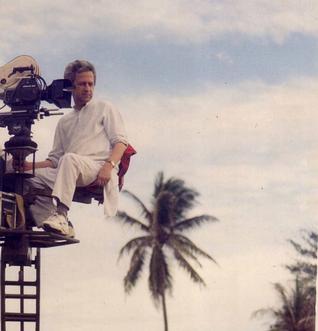

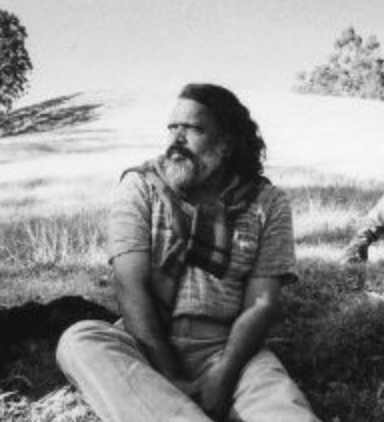

Born in 1940, Shahani has been among the brightest alumni of the Film Institute in Pune where the greatest influence came from Ritwik Ghatak, the controversial film-maker and teacher, and from D.D. Kosambi, the great Indian polymath. After standing first in his course at Pune, Shahani won a French government scholarship to the Institute of Higher Studies in Cinema, in Paris. There he spent a great deal of his time at the Cinematheque, opted for courses in Western music, worked with Robert Bresson on the Femane Dance, and became a keen observer of the cataclysmic events that shook France in May 1968. His first feature film, Maya Darpan, was made in 1972 and was hailed for its originality and sensitivity. Six years after his first feature, he was awarded the Homi Bhabha Fellowship, and the subject of his study was the theory and practice of the epic form. Married to Roshan, who is a close collaborator of her husband in the field of scriptwriting, Shahani is also a regular guest lecturer at the Film Institute in Pune. Maya Darpan received the President's Award in 1972 and a special mention in the Locarno Festival next year. Among the shorts and documentaries Shahani has produced from time to time are The Glass Pane (1966), Manmad Passenger (1967), Rails for the Road (1970), Object (1971), Fire in the Belly (1973), and Our Universe (1975). Tarang is his second feature film.

In an interview with Rajiv Rao and Rafique Baghdadi, published in The Sunday Observer, 29 April 1984 Kumar Shahani speaks at length on his views on the cinema, on film criticism, on the experimental film-maker and on his latest film.

R.R. and R.B.: It's been a long time since Maya Darpan was made. Do you perceive any significant changes that affect filmmakers?

K.S.: It's well worthwhile to try and make films that one believes in. Certainly, the whole environment has changed since Maya Darpan. The change, I think is two-sided, not unilinear. On the one hand, society is getting very aggressive and more and more people are measuring their own selves in terms of rupees and paise. On the other hand, people are more sharply aware of their condition.

R.R. and R.B.: To what extent do you try to consciously shape your political beliefs in your films?

K.S.: I think the biggest mistake being made about films is that if I, for example, photograph you, most people will say that my film is about you, about the middle class, about Bombay, about a man who wears glasses and has a moustache. But it may not be so. That is only what is being photographed...

R.R. and R.B.: Godard said something similar...

K.S.: It is absurd to think that if you are depicting something, that is the content. The content emerges through the way you relate to the object, to what you show, your theme. When people say there is visual beauty in the film, it is deeply connected to the editing, the rhythm, the shot taking, the pattern of movement and also, the sound . . . all constitute the content . . . Look at the majesty of Vanraj Bhatia's music, for instance ... who would say that it is beautiful without implying at the same time that it touched him, that it is was meaningful? Or, take the example of Buddhist art in India. The motifs of burgeoning wealth—the figures, animals, vegetation on the Sanchi gateways—it is the same as the precedent Hindu iconography; yet the meaning has shifted. The Yakshi image offers a world of nourishment. Nature itself is in a reverie, serene, not overwhelming in its power.

When Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel, he was supposedly depicting Christian mythology. But what he did was to assert the human spirit and celebrate the human body . . . something else.

R.R. and R.B.: You received the Homi Bhabha Fellowship to research the epic form. Could you tell us something about your preoccupations with the epic traditions in Indian art?

K.S.: The fellowship was a great thing for me. It helped me a lot in formulating Tarang and releasing the kind of energy which only the epic structure can give you. I long wanted to work on it and signs of it were there in Maya Darpan. Ever since I met Kosambi and Ritwick Ghatak in Poona, I wanted to try and evolve something that would be close to a modern epic. As it happens, other people across the world have been concerned with the epic form—Godard had begun to move towards the epic. Jansco has done some significant work in Hungary. In America, Francis Ford Coppola has attempted it. Rossellini, for many years, worked on the didactic elements in his films with the support of reality. The work of the Soviets after the revolution in 1917 is well-known. The epic tradition overcomes the division between the giver and receiver of art. It is a pity that societies tend to make museum pieces of art when, in fact, the need for it is as natural and instinctive in people as eating and drinking.

R.R. and R.B.: The process of selection of images and how you relate them to each other shapes and colours the content of your film. Considering that two of the teachers who have influenced you—Kosambi and Ghatak—were Marxists, do you think this influence has exerted itself in your films even unconsciously?

K.S.: If you have to contribute anything while working in a tradition of any sort, Marxist or Liberal, you have to be critical of that tradition itself. Tradition grows through criticism. In my film, I must be able to overcome the structure of that very work itself. One must discover something in the process of making the film, not only in the themes one presents.

R.R. and R.B.: There is a lack of a critical tradition in the country. Film critics often resort to making parallels with western concepts and techniques. In your own case, Maya Darpan was seen to be Bressonian, whereas it is deeply rooted in the traditions of this country.

K.S.: I think film criticism is still growing. There is an absence of standards, ironically enough, in the countries that lead in film production—India and the U.S. Often critics make no reference to any tradition, not even the cinematic one. When people, speak of a Bressonian influence, they must specify where it lies. If I say that Ritwick was influenced by Eisenstein, then I must be able to show it: that he went to anthropology for sources of reference, that he used sound contrapunctually and so on....

R.R. and R.B.: There are a number of filmmakers in the garb of experimental filmmakers, who expect to be taken seriously.

K.S.: The experimental filmmaker has difficulty in surviving. By the nature of experiment, any experiment, he is trying to find out a new language. He will accept criticism if it is made within the parameters of his language. In an abstract painting, you may not be moved at all. When Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, everybody was shocked. By the nature of experimental work, it is very rare to appreciate it the first time you see it. If you're uninitiated in certain forms, say classical music, you don't reject the music for that. Tomorrow if I hear an Indian musician trying to experiment with something he has learnt from Korean music, I will be able to get some significance from the slight shift he may make. This is because I am initiated into music. If Kumar Gandharva takes from certain influences of folk music which you or I have not heard of—I would like to find out what it is.

What we have to do in criticism of experimental art is to understand the tradition and then to understand what shift is being attempted; and, within that shift alone can we really appreciate or criticise. It has to be an internal thing to the work of art itself.

R.R. and R.B.: Western critics often claim they have popularised Indian experimental films. Do you feel their critical writing has had some influence in gaining Indian films a wider audience?

K.S.: Certain critics take a lot of trouble and those who do that, wherever they may be from, can come up with some interesting insights. An important fact which I would like to state here is that western critics are not ashamed to say that they like a film. You know that the Cahiers group only wrote about authors they liked.

R.R. and R.B.: How did you come to use the epic form in Tarang?

KS.: The traditional mechanistic structure with the beginning, middle and end, is a dramatic structure which originated in the 19th century in Europe. It was closely related to the methodology of physical science—cause and effect in a chain. As far as I know, science today goes beyond this and accommodates fluctuations. One has to find new ways that are linked to our actual perceptions. Ritwickda and Kosambi made me probe into the epic form. You also see it all around. It enters the consciousness of people in such a way that they can take it home with them.

I believe that people like Costa Gavras who claim to be changing lives are really only doing the instant churning up of emotions.

Immediately after a Costa Gavras film you may feel that the revolution has occurred for you. The next day you are faced with a harsh reality, when you can't change your own family or yourself, or, the timing of that train that you have to catch.

Costa Gavras told a film critic here that before showing the torture of men on the screen he tried it on himself—electric shocks on the testicles. You see how sensation replaces significance. The image of torture turns into a thrill.

As against that the epic form makes the sensuous significant. Every life is treated with respect.

R.R. and R.B.: One critic has stated that Tarang is a story straight out of the Bombay formula film industry turned on its head. . . .

K.S.: What I wanted to do was to take into account the way our traditions are surviving in popular art. Both folk and popular art always have epic elements. Even pulp literature is a distortion of the epic form. A lot of artists in different parts of the world are trying to understand that. Europe and America have certain disadvantages compared to us. In our classical arts, you continue to see a constant dialogue with folk elements, a constant formulisation of folk culture. Europe had lost it but now there is a revival of narrative not only in film but in painting as well.

I genuinely feel that Vivan Sundaram has a greater potential of success in narrative painting than say a western master like Kitaj. I am sure that we are better placed to retrieve the narrative.

R.R. and R.B.: The method of acting in Tarang is different from the one used in Maya Darpan. It was a conscious decision to use that method?

K.S.: The method has evolved from Maya Darpan to meet the demands of the epic. I think the actor's own being should never be denied, if you wish to discover the archetype.

R.R. and R.B.: Like Janaki becoming the mythical Urvashi in Tarang was the idea inspired by Kosambi's description.. .

K.S.: Originally yes. I am deeply inspired by his work and I go back to it again and again. For Urvashi's appearance in Tarang, there were many experiences that came together. Kosambi relates Urvashi to water and fertility. When we were hit by a drought in Maharashtra, I met a lot of women who bravely shouldered the burdens and responsibilities during those harrowing days and I was inspired by their courage. I was shooting a documentary on the drought. Later, when I was studying the epic form I requested my Sanskrit teacher to read for me the Brabamanas' and the Rig Vedic versions of the legend.

R.R. and R.B.: Does Urvashi in your film represent the eternal woman, who is everything—seducer, whore, murderer and all the other characters played by Smita Patil? Or is she also the symbol of the oppressed?

K.S.: Urvashi has fantastic aspects. She is represented in a different way in the Mahabharata. There she tries to seduce Arjuna who looks upon her as an ancestress. In my film, Urvashi becomes the Universal Mother, standing for everyone who is oppressed.

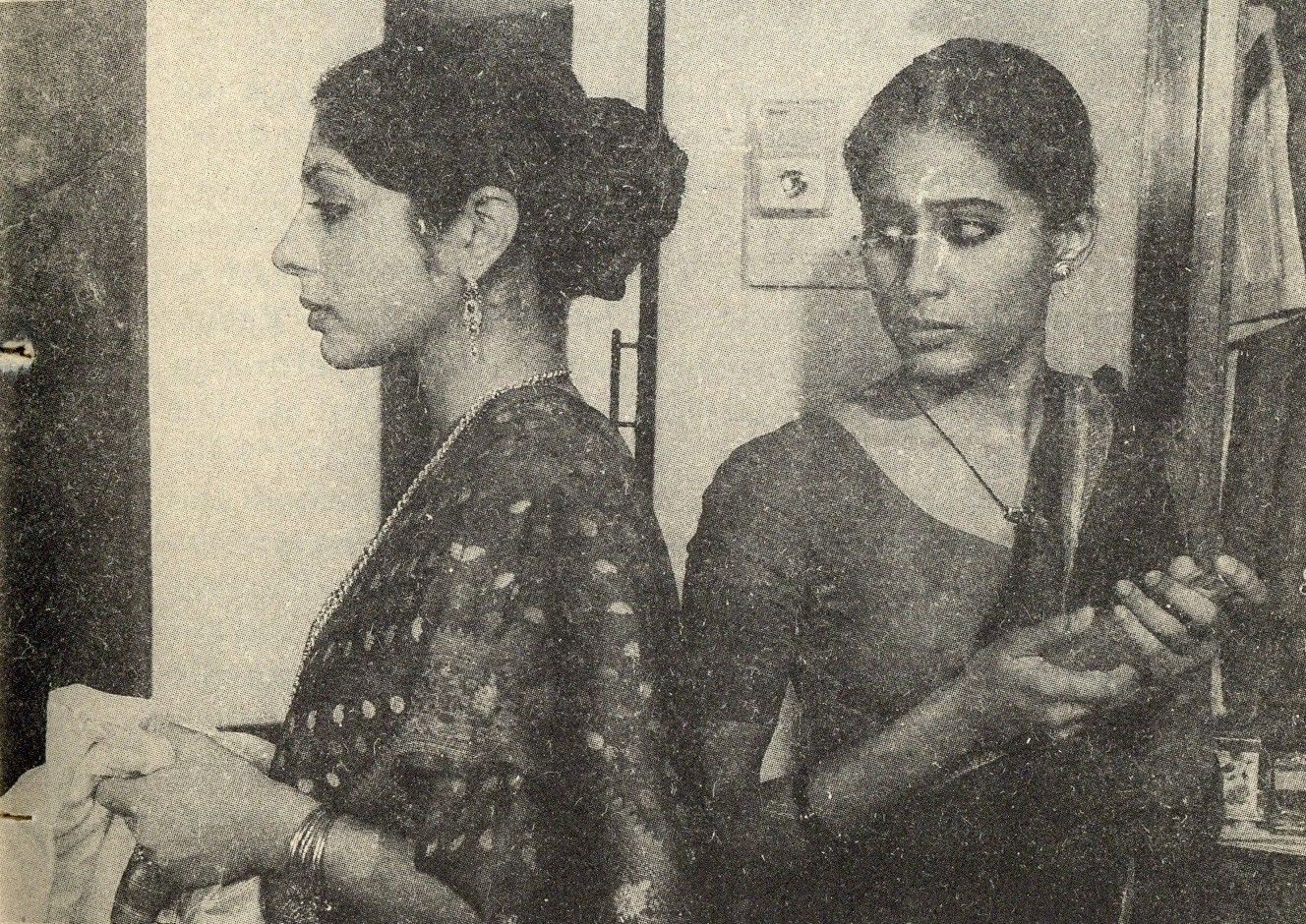

R.R. and R.B.: How do you see the role of Hansa, the wife of Rahul. Is her passive acceptance of events a reflection of the passivity of Indian woman as well as the democratisation of class?

KS.: Hansa is certainly not passive. There is a reference to Ophelia (Hamlet) in her characterisation, evoked through water and flowers. Her name and the images around her relate her individually to the archetype. A lot of tenderness towards Hansa is expressed through the camera. Her own warmth is conveyed through her gestures of giving and her grate... in the song sequence, I wanted her bathed in sensuous light... K K (Mahajan, the cameraman) has done such a marvelous job. . . . Each character in the film, has in fact, his own little world. The individual warmth of character, the potential of the particular actor's presence and the archetype—all are important for me.

R.R. and R.B.: There is a point in the film when the audience feels that everything will be all right for Hansa. This however is also the point of crisis.

K.S.: There is splitting of the personality. Anything can happen at that moment. Things might turn out right or there could be a disaster. This splitting provides the tension.

R.R. and R.B.: You are making a film on the psychoanalyst, Wilfred Bion. What is his essential world view? At its broadest, his vision is comparable to the twin concepts of cannibalistic violence and nurturance found in the symbolic representation of Kali.

K.S.: Yes he was concerned with archetypes, mythology and dreams. His basic concern emanated from the instinct for knowledge. Apart from that he has done work on the behaviour of groups. He has tried to find neutral symbols for the creation of a theory of emotion, symbols devoid of associative or moralistic or other forms of loaded concepts. Finally, two other things are important. His fictional work puts together his different concerns and his grasping of extra-rational reality goes deep into the mystical tradition of the East.

R.R. and R.B.: Bion as a subject is anti-film and anti-drama. How did you decide to make this film and what kind of treatment are you likely to give the film?

K.S.: I have a friend, Udayan Patel, who is a psychoanalyst. I have made a short film, Object, with him. Udayan and his wife Anuradha have been greatly inspired by Bion's work and when they meet him in England, they discovered that he had an abiding love for India. He had, in fact, spent the first eight years of his life in India. He was invited to visit Bombay but he died a few weeks before his expected arrival. It was decided to make a short documentary on him when he was in India. Later, after his death, the idea got expanded through several stages into a feature film. It is visualized as a fantasy.

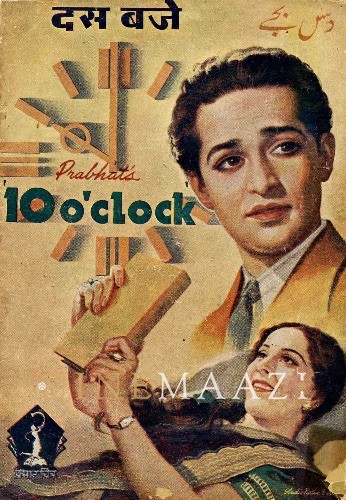

This article was originally published in Indian Cinema 1984. The images used in the feature are taken from the original article and the internet.

.jpg)