Parambrata Chatterjee on his Five Favourite Films

‘Sometimes, not intellectualizing things really helps. Just flow with the moment. Either it works or it doesn’t. Most of the times, it does work.’ – Parambrata Chatterjee

On the eve of the release of Dwitiyo Purush, a sequel to the celebrated Baishe Srabon (2011), the film that established him as a star, Parambrata Chatterjee, who has had an enviable run with class-acts like Chotushkone (2014), Apur Panchali (2013) and Cinemawala (2016), talks to Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri about five films that are closest to his heart.

***

There’s a sequence in the film Samantaral that in many ways defines the actor in Parambrata and his approach to the craft. In the film’s most poignant scene, he tells his co-actor, played by Riddhi Sen, ‘Amar dike ekbar taka na, taka na (Look at me just once, just look at me once).’ The expression in his eyes here is likely to give the most seasoned critic goosebumps. Yet, the actor that he is, Parambrata is quick to break any attempt to mystify his approach to the film or the character. Read on to find out…

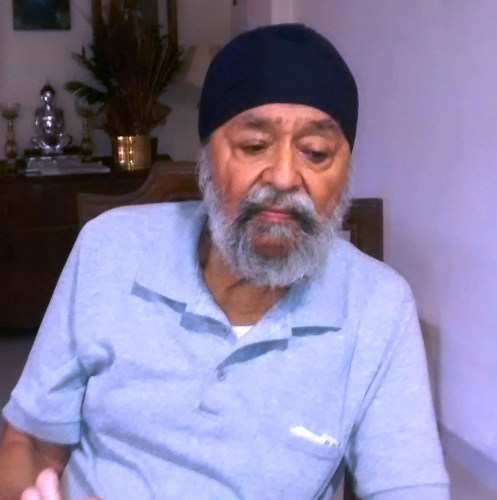

Picture Courtesy: SVF

Hemlock Society (2012, D: Srijit Mukherji)

Hemlock came about in a funny way. I had just finished doing Baishe Srabon with Srijit. It was a stupendous success, and Srijit and I were thinking of what to do next. I knew he was writing a big film. I also knew he had interacted with someone who had moved him quite a bit. A terminal patient. He was rethinking his idea of making that big film. I didn’t know yet that I would be part of the film till he called me and asked if I had dates. I reminded him that Bumba-da (Prosenjit Chatterjee) was supposed to be doing it. He said no, they had discussed the script and Bumba-da himself felt I should do it.

He read the script to me and I thought, I still do, it was one of his best ideas. Though the film was very popular, and Ananda Kar almost became a cult figure, it had its fair share of criticism. In the sense that there were certain subplots that people thought were redundant. The film was about fifteen-odd minutes too long, I feel. But for me what matters in a film is whether it makes an impact holistically, technical glitches and flaws notwithstanding, whether or not it could have been crisper, subplots could have been avoided … these are important but what’s more important is the overall vision. Hemlock was one such film – it came from a very humane idea that made it special for me, and it will remain so forever.

Picture Courtesy: CineMaterial

That year, at the Anandalok Film Awards, I was judged the best actor in the popular category. Something that I never expected. It was more or less a given, at least back in those days, that popular awards chosen through votes always meant hardcore mainstream films. In fact, while picking up the award, I mentioned an incident that happened back in 2003–04. I had just started my career as an actor and was attending the Anandalok awards for the first time. Kharaj-da had been nominated for Patalghar in the Best Actor category. When the nominations were being read out, I remember rooting for him. Kharaj-da, who was sitting next to me, said, ‘You wait and see, I won’t get the award.’ I was surprised given his performance in Patalghar, but he explained that such awards normally went to big stars. And he didn’t win. When it came to Hemlock, I was glad to see an actor winning this award, not a star.

We shot Hemlock in early 2012 … over the last eight years I’ve directed myself, I’ve become a more flamboyant person, more mature, so now I am used to these characters … But back then, I was stepping into the unknown … that was important for me, it will always be a very special film. Even today, people often refer to me as Ananda Kar.

Hawa Bodol (2013, D: Parambrata Chatterjee)

This was my second film as a director. My first film as a director, Jiyo Kaka, will always remain close to me. However, it went completely unnoticed. Many people liked the film, but it didn’t do well. There are two aspects to consider here: one, a film doesn’t do well, but people notice talk about it. Two, it doesn’t do well and people don’t even notice it. I made Jiyo Kaka before I left for the UK to study. I am actually one of the rare ones from the current crop of film-makers to have had the opportunity to make his/her first film on celluloid. It was a film that came straight from the heart, and it was a film about people like us, cinephiles, three boys, three strugglers in Kolkata who want to make a film together and who decide to kidnap a leading heroine to do that. It has its flaws, of course, in writing … I wanted to be quirky, whereas if I were to make it today, I would have infused it with a little more emotion. I would have stuck to the core struggle, the core crisis and not tried to make it mainstream. Jiyo Kaka released in 2011, after I came back from England. I had to go through a lot of hardships to release it, and it didn’t do well.

At that point I was involved in a lot of other films, I was shooting for Baishe, the filming had just finished for Kahaani … both went on to become big successes. Bhooter Bhobishyot happened. It was around that time that Rudra (Rudranil Ghosh) and I were planning to line-produce a film for Workshop, our company. Rana Guha and Sudeshna Roy were supposed to direct. The story idea was mine, and I was co-writing it with Anindya Bose. I was also the creative producer. Beceause of certain developments with one of their films, Rana and Sudeshna-di opted out a month before the shooting. That’s when I said, I will direct this one. I was already writing it. That’s how Hawa Bodol became my second film as director.

I was quite happy with the way the film shaped up … the writing, the music by Indradeep-da, Arijit’s (Singh) first big Bengali song. By the time it released, there was a good buzz about it. It was an underdog, new producers, new team, I took a lot of responsibility of the marketing myself, along with a few friends of mine, within a limited budget … ensured it got fantastic visibility in terms of marketing. Not that we spent a lot of money, but we played it right. The trailers were out, teasers were out, the songs were out, and the song ‘Bhoy Dekhash Na Please’ became very popular. The film released with a few other big ones. Yet, it went on to make a lot of money. I could see people at the theatre really enjoying the film.

Picture Courtesy: IMDB

It was a difficult film in terms of performance, switching between the characters. I shot it with a lot of care, with limited resources, and I still feel it’s a very cute film. I don’t always say that about films I make … I’m very objective about them. Most of the times, I don’t even like the films that I act in. This, however, was a film made very genuinely, but I realized that we Bengalis have lost our sense of humour, our ability to look at serious issues through a humorous prism … the apparent light-heartedness of the film came in the way of people within the industry taking it seriously. Maybe they would have if the same philosophy was conveyed in a grave, dark, grim way.

I realized that people in Bengal have a lot of opinion on cinema but they have not reckoned with contemporary masters of world cinema. Like, for instance, my favourite contemporary film-maker is Emir Kusturica. He is the only one to win the Palme d’Or consecutively for two years. His films are overtly political, at the same time incredibly funny, almost nonsensically funny. Most of his films revolve around the identity of being a Balkan, but in a very funny way, almost spoof-like. It is entirely my opinion and everyone is free to refute it, but Hawa Bodol was not taken seriously despite making a lot of money, probably because it was a comedy, at the same time, one that didn’t wish to remain just a comedy.

Hercules (2014, D: Abhijit Guha and Sudeshna Roy)

This is another film that hasn’t got its due. Again, a very philosophical take … by the time I started shooting for Hercules, I had started realizing that I didn’t want to make films only for fame or money. Maybe I inherited it from my grandfather, or maybe because of my upbringing, I feel a film has to offer something beyond those two hours in the theatre. Or in front of the television. Something to take away, long-term. Maybe you could say there was an element of activism … around 2013 I was coming to terms with this aspect in me. That I will always choose a film with a cause as opposed to a film with a lot of glitz and glamour. To the extent that my girlfriend used to pull my leg by calling me, ‘Oh little Ghatak!’ It was under these circumstances that I bumped into Hercules. I thought that this script encompassed all the philosophical crises, all the existential crises of the marginalized. That really moved me.

Picture Courtesy: pinterest.com

I can’t tell you how much I identified myself with the character. At the same time, there was this house, this old house … I have a thing about old houses of Calcutta. I have expressed my concerns with the government about restoring and preservation of old houses, because I feel they are not just heritage. They are more than that. They represent the character of a place. They represent time, a legacy. All these big apartment buildings that keep coming up these days seem to me like they have been hurled into the world, into a post-apocalyptic world. Whereas these quaint houses, they give me a feeling that, oh there was a world before, a harmonious, aesthetic world.

Sure, the film had a few issues … for instance, I thought the climax should have been scaled up. After all the build-up, it falls flat. It’s too tame a climax. It should have been much bigger in scale. I fought with the director about this as well while shooting the film. I think it is not always money that decides how you scale up. It is also the way you shoot it. I would have saved a little more money on something else, and I would have, to begin with, shot it in a bigger space. With more people. Giving it more scale, giving it more magnitude so the audience gets to relieve the outrage. It could have been done with a lot more style, I would have at least got hundred more junior actors to do it, I would probably have done some green screen … I would have saved somewhere else and spent 10 lakhs on that. We needed to convey the man’s desperation, he is fighting for the first time … he knows very well that he’s going to lose, right? He’s fighting a lost battle against the local goon, and it’s the people who pick up the fight. That needed to be bigger. It needed heightened music, more dramatic shots, it needed to make a bigger audiovisual impact. We tend to forget that things like production value and scale have a direct influence on audience’s minds. At the end of the day, the audience doesn’t go to watch the film like a critic. They go to interact with a character, see him fail or win. If the character fails, they come out weeping and with one kind of takeaway, if he wins, they come out with another kind. But you mount it to that level, and then let it fall, it’s like premature ejaculation for the audience. That is what happened with the film. Despite that, notwithstanding the weak climax, I have a soft corner for it given the basic politics of the film, and a truly non-filmi character.

Samantaral (2017, D: Partha Chakraborty)

By the time I was shooting Samantaral, I had had quite a few successful films under my belt. Baishe had happened, Hemlock had happened, Chotushkone, Apur Panchali, Proloy had happened, Cinemawala. So expectations around my films were big. However, Samantaral happened at a time when I was going through a lean phase as an actor starting in 2016.

Hemanta, an adaptation of Hamlet, a film with huge expectations, failed. Zulfiqar was a big hit, but the film didn’t garner critical acclaim. Also, with a big ensemble cast, including Dev and Bumba-da, somehow that Anglo-Indian act of mine got lost. Samantaral came at that point in time. I was dubbing for something in the studio when some people came to me to narrate a story. We tend to form an opinion about people when we look at them, right? Time and again I have been proven wrong and I am so glad about that. I was not at all impressed with the people who came for the narration – a real-estate dealer, Mr Saha, and his overenthusiastic son Souvik … I thought it’s going to be a shitty story, a very regular one, so what’s the point? My only hope was that it was written by Padmanabha-da and he had told me, ‘Just listen to it.’ Nothing else. ‘Okay,’ I said. ‘I will give it a shot anyway. Let’s listen to them.’

However, once they started narrating the story, I was zapped! Slowly I got to understand this marginalized character – I sat up and thought, ‘Where is this going?’ I wanted to know – what is this man actually? They were unwilling to give away the story in its entirety and wanted me to read the script. I was so curious that I went back home, made myself a drink and started reading it in the evening. I read it one go. By the time it ended, I was sobbing uncontrollably. I called Souvik and asked, ‘Who has come up with this story?’ He said, ‘My father.’

They came over to my office the next day. I asked Mr Saha about what inspired him to write a story like that. He said he had seen people like these all his life, how they were bullied, tormented. How humane and topical it becomes in today’s time of championing transsexuality and alternative sexuality. I was fascinated with that. But a doubt lingered … I was going through a lean phase in my career and if I played a transgender character or a transvestite, how would that affect my fans, particularly the women? How would it affect the image of being a hero? I hated myself for thinking that way with my sort of upbringing and sense of politics. I was aware that a large section of the audience would not take to it.

Remember, this is much before Nagarkirtan. I had a very typical ‘hero’ image. Riddhi has done a fantastic job in Nagarkirtan. But he did not have the set image of a hero when he did it. So I spent three days just thinking about it. Then I said, let’s just do it, without expecting anything to come out of it. I was anxious about how they were going to treat it, handle the subject. The director was new with one forgettable film to his name so far. I remember Riddhi had already started shooting for the film before me. I called him and asked how it was going. He said, nothing out of the ordinary … rather straightforward and simple … That was a relief.

Picture Courtesy: moviebuff.com

Let me share something funny … it might come as an anticlimax and amount to demystifying my performance. I played the character by the clichés. I didn’t try to intellectualize it. I didn’t practise any method. I just let them make me wear those costumes and that automatically gives you a feminine gait. I just let the moment sink in and nothing else. Sometimes, not intellectualizing things really helps. Just flow with the moment. Either it works or it doesn’t. Most of the times, it does work. People from transgender communities reached out to me. I am not someone who particularly champions this cause. I had never really thought very passionately about the sexually marginalized. However, that they are people at the margins, that connected, that clicked with me. The rest, I think, happened purely by instinct.

Shonar Pahar (2018, D: Parambrata Chatterjee)

Shonar Pahar has a number of streams flowing into it. It is an intensely personal film … that is evident. That I spent two years with this script helped me get rid of the unnecessary personal elements in it. I wrote it with Pavel. I told him the story, then he wrote the first draft. I stayed with that for two months, then he wrote it again. I consulted him again after a while. He wrote the third draft. Then we left it for some time. We kept going back to it. With personal stories you run the risk of puking, vomiting it all out. They are so dear to you that you don’t feel like letting go of a single strand. But a film has to be objective. People have to identify with it, enjoy it … that is important. This was a personal film that had to be made slightly impersonal. That is one stream.

The other stream is that I was coming from the failure of Lorai, as a film-maker. That was a film made with a lot of scale, a big budget, a lot of stars, great locations, lofty messages. But it flopped. There was a lot of pressure on me to make a film that was going to be successful. To add to my problems, my producer wasn’t in the best place at the time. Nevertheless, he stood by me. I was supposed to make a different film for him. He supported me with Shonar Pahar, despite knowing that the other film that I was supposed to make would have fetched him a better satellite deal. I have to give it to him. He continues to be a friend and we are still working together.

Picture Courtesy: allaboutbanglacinema.org

Not just the child character … they also thought that the film would be overtly sentimental, of the same dramatic pitch as Uma and Hami. Shonar Pahar has a very different pitch. Much toned down, say, in musical parlance, if Hami and Uma were E major, mine was B flat. I made with much heart and passion. I really wanted people to watch it, but the film wasn’t marketed and publicized well, thanks to the problems my producer was facing. There were few takers for it on the day it released, few people knew about it. Whatever little I could do, taking the kid to different events and to radio and Facebook live and Instagram live, getting Tanuja aunty to do certain things. That was all.

It was only from Saturday that the screens started going red. Filling up slowly. I wasn’t even checking BookMyShow or anything. One of my partners called me and said, ‘Have you checked BookMyShow? I think things are changing.’ It was purely because of word-of-mouth that the film did very well on three consecutive weekends, in the limited number of screenings that it had.

I modelled Tanuja aunty’s character quite a bit on my mother’s experiences. We made her a little older than what my mother was. However, it will be wrong to think that it only came from my childhood, from my personal experiences. It’s a sort of eulogy to the way we grew up which is not there anymore. The way we grew up learning certain tenets of coexistence, of opening up the world of our imaginations, creating a little world of our own. Without anything, with no mobile games, no phones, no iPad, nothing. It’s a tribute to a lost way of life. All of these made it a most satisfactory experience.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)