Memory, Ageing and Death: Suman Ghosh's 'Experiments' with Soumitra Chatterjee

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

In the course of four films with Soumitra Chatterjee, filmmaker Suman Ghosh cast the actor in some of his finest latter-day roles. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at some common themes that bind these disparate films together…

***

‘I prayed to rediscover my childhood, and it has come back, and I feel that it is just as difficult as it used to be, and that growing older has served no purpose at all.’ – Rainer Rilke

It says something about the film awards system in our country that Soumitra Chatterjee received his first National Award for Best Actor in 2006! But it also says a lot about the film that fetched him the award and the filmmaker who made it. Podokkhep, directed by Suman Ghosh. What makes it even more creditable is that this was Ghosh’s directorial debut. Over the next decade and a half, Ghosh went on to create an enviable body of work with Soumitra Chatterjee in the lead – in films that comprise the best of the legend’s latter-day performances. In fact, over the course of a ten-hour-long interview session that I had with him, the actor singled out Ghosh for special mention among contemporary directors whose work excited him. No wonder that between 2006 and 2019, he acted in four films helmed by Ghosh: Podokkhep (2006), Dwando (2009), Peace Haven (2015) and Basu Poribar (2019) (I leave out 2012’s Nobel Chor, where the thespian had a guest appearance).

Looking back, watching the films all over again in the months leading up to the actor’s death and after, I was struck by a thematic unity that binds them. This is not to say that the films are similar in any way. In fact, no two films could be more dissimilar than the allegorical piece of black humour that Peace Haven is and the almost-gothic chamber drama Basu Poribar. Yet, running through all four films like a subterranean thread I discerned the universal themes of memory, ageing and death – the nebulous nature of our memories, the loneliness inherent in growing old and the inevitability of death. I am not sure if the filmmaker had any such unity in mind – in casting Soumitra Chatterjee in these characters – or if the films developed organically, and I was reading meanings in them given the backdrop against which I re-watched them. But it does make for an interesting way to look at the four films as a single unit.

In an earlier interaction with me, Suman Ghosh had mentioned, ‘As far as hobbies are concerned, well, there’s reading, reading and reading.’ It is no wonder then that his films are often inspired by ideas from literature and are full of literary allusions. Podokkhep, which according to the director had its genesis in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story ‘The Curious Case of Benjamin Button’, begins with a quote from Graham Greene’s story ‘May We Borrow Your Husband’: ‘At the end … the only love which lasts is the love that has accepted everything … even the sad fact that in the end there is no desire as deep as the simple desire for companionship.’ It is this that lends poignancy to Shashanka’s (Soumitra Chatterjee) relationship with the five-year-old Trisha, at the core of which lies his loneliness – he has long retired from work, he is a widower and his daughter, Megha (Nandita Das), albeit conscientious and loving, has her own life and career to occupy her.

‘My first film Podokkhep was the story of an old man and his relationship with a five-year-old child. It was about the cycle of life where at the end, a human being becomes like a child, going back to the womb in a sense. Soumitra-kaku was like that in real life. While reminiscing about his relationship with my daughters Maya and Leela I keep thinking about that. About four years ago, Deepa-kakima (Deepa Chatterjee) and Soumitra-kaku wanted to see my daughters, Maya (four years old at the time) and Leela (two years). Once they reached Soumitra-kaku’s place they promptly realized that they would have to entertain themselves. They started making their place some sort of fantasy land, which apparently required ransacking the elegantly decorated living room. My wife and I were extremely embarrassed, but the person who indulged them the most was Soumitra-kaku himself. His only worry was that their house was not suitably childproof. Maya and Leela were pleasantly surprised to get a play mate ... maybe seventy-five years older than them. But who cares...’ – Suman Ghosh

A couple of early exchanges give an indication of what Shashanka seeks and lacks. His daughter lovingly scolds him for nicking his cheek while shaving. It reverberates in his mind as a voiceover of the ‘child’ Megha as he stares vacantly at the leisurely rotating ceiling fan when it is time for his afternoon nap. It’s a moment filled with the indescribable loss of realizing that one’s children have grown up and moved on. The second exchange involves a friend Sunil Bhattacharya. This is the only time in the film till Trisha enters his life – and to an extent even after – that Shashanka actually laughs. The friends play chess, discuss Shombhu Mitra in Raktakorobi, fixed deposits and interest rates, the financial losses Sunil has suffered in the recent past, and Gaugin having been a stock broker, at the end of which Sunil has a throwaway line – which you are reminded of only later – about a group of elderly people exercising in the park nearby: ‘Bachar ki shawk’ – what a strong desire to live they have.

This exchange with Sunil throws into relief the vacuum in Shashanka’s life. Time hangs heavy on his hand till Trisha comes into the picture and literally sweeps him off his aged legs, providing him a second wind. There’s a series of delightful exchanges between the two – quarrelling over the TV remote (he wants the news, she wants cartoon); he teaching her to make paper boats and she using the day’s newspaper, which he hasn’t yet read, to do so; she espying him reaching for a smoke and promptly reporting it; he escorting her to school and gazing lovingly at the cacophony of children at play, all of this culminating in their daylong outing – the park, the tram ride, an ice-cream treat. Shashanka returns home that evening with a long-lost contentment about him only to discover that his friend Sunil has passed away.

In a sequence that plays out largely in silence, Shashanka comments about ‘the whole perspective’ (of life) coming together only now – the joy of companionship irretrievably offset by death. The camera holds his face, suffused with a mix of myriad emotions, before cutting to father and daughter going over a photo album, Shashanka remembering the mundane minutiae of life as it used to be. In a few brief strokes, Suman Ghosh lays bare what remains of Shashanka’s life. Including the potent image of a tree which he distinctly remembers but whose fruit he cannot recall for the life of him (‘adbhut phol hoto laal ronger’ – it bore a strange reddish fruit).

Which cues into the film’s climactic sequence, one of great emotional heft: a picnic outing involving Shashanka, Megha, Trisha and Trisha’s parents. In a masterstroke, Suman shoots the sequence to the backdrop of Moushumi Bhowmik’s eloquent ode to dreams and loss: ‘Shopno dekhbo bole’. Soumitra Chatterjee here provides a masterclass, his face and body language defining regret and consternation – watching Trisha in her father’s arms as the lines ‘Kothaye shanti paabo bolo kothaye giye’ (tell me where do I find peace) play on the soundtrack. It’s a moment filled with a lifetime of longing and regret for the times that are gone. The song continues as Trisha takes Shashanka away, running through the park, with him panting and puffing, barely able to keep his eyes open with the exertion (ironically to the line ‘Tai shopno dekhbo boley aami duchokh petechhi’). It is almost as if it is Shashanka’s last stand to hold on to his memories, leading him to the tree in the photograph with the red fruit in full bloom … or does it? As Shashanka goes round and round the tree in wonder and the camera keeps circling him before he collapses, one is left wondering about the nebulous nature of memories.

If Dwando fails to evoke these aspects as strongly as Podokkhep it is because the central conflict in it pertains to a woman having to decide whether to abort the child she is carrying – which leads only tangentially to the conflict experienced by the irascible Dr Mukherjee (Soumitra Chatterjee). For Sudipta (Ananya Chatterjee), her relationship with Anik (Kaushik Sen) has become a matter of habit over ten years of marriage. She has an affair with a colleague Rana (Samrat Chakraborty) – starting off almost as a dare at an office party (‘Only those who risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go,’ the director has Rana quoting T.S. Eliot). When she becomes pregnant, she more or less decides to come clean with Anik, only to have her plans stymied as the latter suffers a brain stroke and has to be operated upon. That is when she lands up at door of Dr Mukherjee, wanting to know Anik’s chances of survival. The child she is carrying is not his, and if he lives, the child has to be aborted. ‘In the lie there can be love, in truth never,’ she tells Dr Mukherjee.

The film comes into its own only around the hour mark when Dr Mukherjee learns of Sudipta’s predicament. He is initially reluctant to meet her and instructs his house-help to tell her, ‘Badi nei, moray gechhe.’ (He isn’t home, has passed away.) But relents in the face of her perseverance. The remaining 30 minutes are yet another masterclass by the actor. One can only marvel at how he lends musicality to the parts of the brain – ‘the tentorium … cerebellum … a pale delicate structure reminding you of the whirl of a veiled dancer’ – or equates the delicacy of a brain surgery to poetry, in his words the anatomy of poetry, the poetry of anatomy, quoting Walt Whitman: ‘I am the poet of the body, I am the poet of the soul.’

However, Sudipta’s predicament lands him in one of his own – how far will his appraisal of Anik’s situation lead Sudipta to take the decision of aborting the child. Does either of them have the right to decide on the life of an unborn child? That is when the film delves into the tropes of memory and death as Dr Mukherjee finds himself reminiscing – with the disclaimer ‘If I have the permission to indulge in some sentimentality’ – about the past, involving his wife Neela. It’s as poignant a sequence as any in Podokkhep as he describes their efforts at having a child and the agony of holding a still-born in his arms. They had thought of Aripra as her name – the flawless one – and Suman Ghosh gets the best out of Soumitra as he says: ‘Is this the outcome of years of prayers?’ It is the only time in his life that he has prayed, says Dr Mukherjee, before the realization dawns on him that life does not halt and he decides to dedicate his life to ‘exercising the sentimental proteins of the brain’. There is something strangely affecting in the way Soumitra Chatterjee puts across the agony of reliving his memory and for a moment providing a glimpse of the man behind the grumpy exterior.

Fittingly, given the actor’s expertise with recitation, Suman Ghosh ends the film with Soumitra Chatterjee quoting from the Mahabharata: Na narmayuktam vachanam hinasti na strishu raajan na vivaahakaale/Praanaatyayee sarvadhanaapahaare panchaanrutaanyaahurapaatakaani – which basically lists the five situations in which telling a lie is not sinful. In what stands testimony to the actor’s quest for perfection, Soumitra Chatterjee actually called up Nrishinga Prasad Bhaduri, an Indologist and authority on the epics, to understand the meaning and ensure he had the pronunciation right.

With Peace Haven this engagement takes a delectable turn. This, as the director says, was a tribute to his father and uncles, who time and again in their conversations made a mockery of death. Over a mere 75 minutes, Suman Ghosh weaves in an experience that is as morbidly funny as it is haunting.

The film begins with a man’s death throes on the soundtrack, the ticking of a clock, the wail of an ambulance siren, over a blank screen. His friends Prabhat, Sukumar and Achyut – Paran Bandopadhyay, Soumitra Chatterjee and Arun Mukherjee, respectively, in what is possibly the finest piece of ensemble performance in Bengali cinema in recent years – realize that Pranab’s son, Ani, who stays abroad, won’t be able to make it in time for the funeral and there is no facility enabling the preservation of the body long enough for the son to return. There are only two mortuaries available, one of which has a problem with refrigeration, while the other, called ‘Peace Haven’, is overbooked (a VIP politician and film star have laid claim to the only available spaces). Perforce, the last rites are conducted by Ani’s friend Raktim, who has one hand glued to a mobile phone at all times.

To forestall the possibilities of such indignity, the friends decide to build a mortuary of their own, towards which end they undertake a surreal journey that affords the filmmaker an opportunity to comment on memory, ageing and death. It is in effect a road movie like no other as the filmmaker strikes the most delicate of balance between gravity and levity.

Consider, for example, the trio’s visit to Peace Haven to check out the facilities. The caretaker, a decrepit old man called Nimai – delightfully played by Suman Ghosh regular Nimai Ghosh – whom one of the friends describes as ‘a living dead body’, shows them three recesses supposedly holding Mother Teresa, Jyoti Basu and Robi Ghosh. What adds to the absurdity of the sequence is the discussion that follows: all three personalities in the cells are short, while the friends themselves are rather tall. The response from the caretaker – that he could fit them all in one itself if need be – is a hoot. There’s also a class system for the alcoves – at Rs 5000, 10000, and 20000 – depending on facilities (teakwood, imported chemicals … is a barber service included in the Rs 20000 bracket, one of the friends asks). Or for that matter, the way they discuss dressing up their dead friend for the final journey – looking for his dentures, draping him in a shawl (advisable, given the heat?). This segues into a later discussion the friends have on whether the feast that precedes and follows their death ought to be vegetarian or non-veg (there’s even a tiff between the friends arising from a confusion: is the feast for the opening ceremony of their mortuary or their shraddha), whether to carry designer glasses or the snuff box in the coffins that will hold their bodies till their children arrive for the cremation, whether to employ still photography or videography. All of these delivered deadpan with utmost solemnity.

Complementing the well-thought-out absurdity of these sequences are moments of quiet contemplation, for example, Achyut gazing in passing at the framed footprints of his deceased wife. Or the dreamlike encounter each friend has with aspects of their past – Achyut meeting his wife, wearing the earring and sari he had bought with an increment, who complains about how neglected she felt all her life given his workaholic nature, or Prabhat coming across his father (Paran in a laugh-out-loud double role, taunting his son for planning his own cremation with such meticulousness, imported chemicals and oils and all, while in his time he was just consigned to the poor old khatiya, not even an electric crematorium). In the most eloquent of these interactions, Sukumar finds himself in the middle of a ruin where he stumbles on his high-school biology class and a discussion on the functioning of the heart, followed by a doctor pronouncing his cancer having spread beyond redemption. (‘We are ready for you … it’s your turn’, the doctor announces ominously, as Sukumar looks on with something approaching fear.)

This feeling of abject terror in the face of death is reinforced by Achyut’s trancelike experience of being part of a funeral procession where he realizes that the body on the bier is his. He keeps running away till he reaches a dead-end (no pun intended) and the only words he can utter to ward death off is: ‘I have not had a shave!’ In another sequence, Pranab speaks about his encounter with a bat which leads to a discussion on bats facing extinction, which I quote because it so tragically conveys the feeling the old have of having outlived their utility.

Achyut: Do bats have a value in the food chain?

Sukumar: Do you?

Achyut: No. That is why we are on our way to extinction.

All this leads to the film’s pièce de resistance, the sequence by the beach bathed in a white light. In a series of fade-ins and fade-outs devoid of all dialogue, with just a trumpet sounding a dirge, we see a lighthouse, the sun rising in the horizon, we encounter the characters and elements we have come across in the film – Raktim with his cell phone, the caretaker at Peace Haven, the newspapers and milk pouches accumulating outside Achyut’s home, the bat lying dead, a gaggle of children in front of a blackboard, even the dog that has followed the three friends all thorough the road trip (echoing the Pandavas’ trip to heaven) and a full-fledged funeral feast. The sequence gives way to Sukumar reciting the lines:

Aaj ke bhorer alo e ujjal

Ei jiboner padda patar jol

Tobuo e jol

Kothha theke aashe

Ek nimeshe

Kothaye chole jaaye

Bujhechhi aami tomake bhalo beshe

Raat phurole podder pataye

The droplets on the lotus leaf of life sparkles bright

In the light of dawn

Yet no one knows

Where it comes from

And where it disappears in a moment

It dawned on me

As I fell in love with you

At the end of the night

Just like the lotus leaf

‘At around 10 p.m. someone from production informed me that Soumitra-kaku wanted to speak to me. We were supposed to shoot the last scene of Peace Haven at 5 a.m. the next day on the beach. I rushed to his room. He was sitting alone, preparing for next day’s shoot. He asked me, ‘Suman, explain this scene to me.’ My brief” ‘This character was written with you in mind. A rational scientific mind, non-sentimental, a brilliant sense of humour, nonchalant about death, even mocking death. Now imagine the moment just before your death. You are facing the ocean, facing death. Think of your life … the past 80 years. Now you know this is it. The end. What do you want to say? Let the scene flow from there.’ There was a brief moment of silence. He looked at me and said, ‘Okay. Thank you.’ I left the room. I did not know what he would do. Tagore and Jibanananda were like his spiritual mentors. He chose a poem by Jibanananda to bring the scene to life.’ - Suman Ghosh

Having reached journey’s end, the three friends are seen sitting on a bench with the vast expanse of the sea behind them as Achyut asks the question that lies at the heart of the film: ‘Ei ze 75 ta bochhor katailam, is equal to ta ki hoilo’ – what have these seventy-years of our lives amounted to. (The director mentions that this is a verbatim reproduction of his uncle Sundar-kaku’s observation one afternoon.) Sukumar, by far the most composed of the three friends, breaks down. The camera moves up for a panoramic view of the beach, the dog to the left of the frame, the lighthouse to the right – and no answer to Achyut’s query forthcoming. One lives, one accumulates memories, one ages and death comes as an end.

If I began with Podokkhep and end with Basu Poribar, it’s not just because the films were made in that order but also because the themes that I mention kind of reach an apogee with Basu Poribar. Inspired by James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, the basic story – a family get-together to celebrate a fiftieth wedding anniversary – provides just the right framework for a journey to exorcise the ghosts of the past. It begins with Pranab’s (Soumitra Chatterjee) voiceover of a letter (itself a dead mode in this era of emails, Facetime and WhatsApp), inviting his son Raja (Jisshu Sengupta) and daughter-in-law Roshni (Sreenanda Shankar) to commemorate his fiftieth wedding anniversary with Manjari (Aparna Sen). The words of the letter provide the film with its theme: ‘At this age there’s nothing much to do but look at the past … reminisce, our days are numbered.’

Though the occasion is festive and everyone – Raja’s sister (Rituparna Sengupta) and their relatives Tonu (Kaushik Sen) and Pompi (Sudipta Chakraborty) – puts on a bright and happy face, there are enough indications that skeletons abound in the cupboard, aspects that are either not spoken of or are hinted at in hushed tones. There’s Tublu (Saswata Chatterjee), Pranab’s nephew, who scrupulously avoids being with his relatives and keeps roaming the abandoned grounds surrounding the palatial mansion ‘Komolini’. There’s the new bride Roshini who, despite being asked not to, goes exploring the ‘purono rajbadi’, now a ruin, moss-covered, overgrown with creepers, symbolic of all the memories we want suppressed. The old mansion itself becoming a character, hiding in its nooks and corners secrets that the family prefers to forget with their selective remembrances of happy summers past. In this, the director is aided immensely by another master at work – composer Bickram Ghosh, a regular collaborator with Suman. Bickram’s plangent sarod strains as Tublu wanders around the mansion is fittingly elegiac.

However, memories have a way of finding their way through – and Suman Ghosh uses two extraordinary set pieces to unmask the truths that have been buried for decades. In the first, the family gathers around a sofa set and there’s a lot of banter as the younger generation goads Manjari and Pranab to talk about their past. This is the past everyone is comfortable about, these are happy memories, though cutaways to Tublu ambling across the grounds and a couple of dialogues cast an ominous shadow. At the outset of the group settling down around the sofa, Manjari says: ‘Is there anything that remains hidden after fifty years?’ As it turns out, there are. Towards the end of the scene, Raja’s sister, going through a troubled marriage, observes wistfully, awed by her parents having stayed together for 50 years: ‘There are so many things that stay hidden even after fifty years, no?’ Fittingly, the sequence ends with an elderly relative’s rendition of ‘Aami onek cheye o parini bhulite tomake’ (I haven’t been able to forget you despite trying my best) – a song whose relevance reveals itself only towards the end, when one learns of Manjari’s secret.

Between this sequence and the other set piece, there are a number of little moments that evoke the shadow memories cast on our lives. The way Manjari fleetingly caresses the do-tara, the conversations around the sweetmeat jalbhora from the well-known Surjo Modok, the brother and sister reminiscing about long-ago summer vacations and the searing sequence between Kaushik Sen and Rituparna in the room with the hunting trophies where Tonu comes clean about his sexuality. And in all of these there is the overarching sense of people seeking solace in forgetting and life’s inability to grant you that.

All of this leads to the climactic set piece at the dinner table which is as fraught as the first one was serene. It begins with a slightly tipsy Pranab, still unaware of the potential the truth has of breaking free, toasting the family, his voice full of pride in his ancestry, the blue blood running through his veins, as he recites a poem by Tagore. But the ghosts of the past will not lie buried any longer, and with Tublu egging them on, the edifice of a carefully nurtured past comes crashing down.

As the rain that has threatened to break all day comes pouring, and Tublu’s voice soars over the landscape, each member of the family is left to ponder about what their lives amount to in the larger scheme of things. The film comes to a close with a chastened Pranab’s pensive voiceover (written by Soumitra Chatterjee himself in what could be a fitting epigraph to a glittering career), the muted strains of ‘Barsan lagi re badariya’ accompanying it: ‘Did it rain with this intensity all those years ago? … I do not have the answers any more … But this much I realize today. Howsoever entangled we are in this small circle of our individual lives, it has no bearing on the larger rhythms of nature. A curse from the womb of the past raises its fangs to sting us, reminding us of the eternal truth: that there exists something infinitely larger beyond our personal trials and tribulations. … The patter of the rain makes me experience something deeper than the fragility of ancestry, the fading pride of a nebulous past, and even the crevices in my apparent success.’

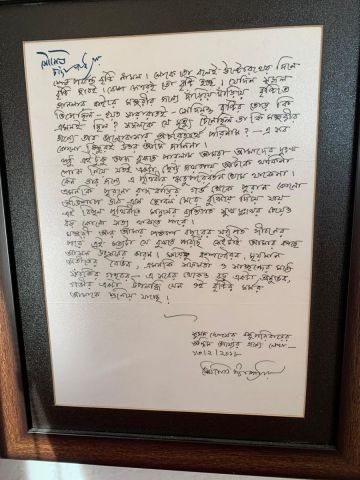

The director mentions wanting to convey the essence of James Joyce’s philosophy which come alive in the last couple of pages of ‘The Dead’. ‘I consider this one of the finest pieces of writing ever in the English language and there was no way I could bring out its essence in Bengali. There were only two people I knew in Bengal who could do that, Shankha Ghosh and Soumitra-kaku. I was thinking of asking another poet I know, when Soumitra-kaku himself said: “Why don’t you let me translate this – if you don’t like it, you could throw it away and get someone else to do it.” A couple of days later, he called me home and narrated it to me. That is what we have as the end narration in the film. I have framed his translation.’

It’s a monologue that captures the essence of the film. The past lives on in us, with all its bittersweet memories. Despite our efforts to look at it through nostalgia-tinted glasses, uncomfortable truths have a way of seeping through. And the dead often cast a long shadow over the present, the living. Fifty years is just a matter of time… and yet, not quite…

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)