Uttam Kumar: The Mahanayak as Producer and Director

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

The legacy of Uttam Kumar as an actor and star remains unchallenged even forty years after his death. But he donned many other hats as well – he was as successful as a producer and director, was a singer and also composed music. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at his contribution to cinema as a producer and director.

With the perspicacity that marked all his observations, Satyajit Ray said of Uttam Kumar: ‘I understand that Uttam worked in something like 250 films. I have no doubt that well over 200 of them will pass into oblivion, if they have not already done so. This is inevitable in a situation where able performers outnumber able writers and directors. Even the best of actors loses his edge and languishes without a steady supply of worthy material to keep him on his mettle. It is even worse with stars, whom circumstances have brought to a pitch where they must stick to their image or topple.’

And though it is true that most of Uttam Kumar’s films have not aged well and do not quite stand the test of time, it is equally true that, as Ray observed, ‘an artiste must always be judged by his best work’. On that count, Uttam Kumar’s best has seldom been bettered by anyone in Bengali cinema in the forty years since his death. What makes his work in cinema even more remarkable is that it was not limited to acting. He also had an enviable degree of success as a producer, director, singer and composer. He composed the music for the 1966 film Kaal Tumi Aleya, and its songs ‘Ami jai chole jai’ (Hemanta Kumar) and ‘Moner manush phirlo ghare’ (Asha Bhosle) give an inkling of his credentials as a composer. His understanding of film music and playback has been well documented with even Soumitra Chatterjee acknowledging the lessons he learned from Uttam Kumar on this aspect of cinema.

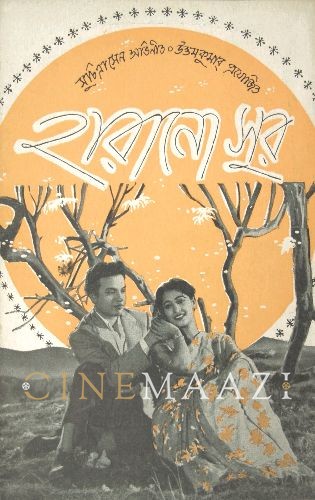

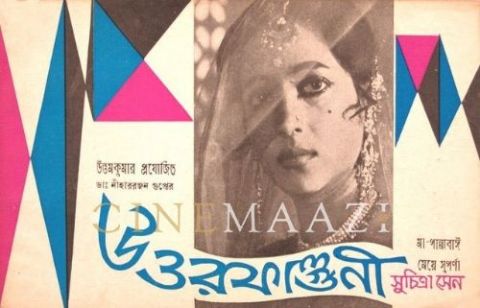

As a producer he had an uncanny sense of backing just the right film as evidenced by the almost 100 per cent success rate of these films at the box office. But equally important in his choice of films as producer is that they hold their own among the best of Bengali cinema even sixty years after they were made, be it Harano Sur (1957) or Saptapadi (1961), under the banner of Alochhaya Productions, or Jatugriha (1964), Grihadaha (1967), Bhranti Bilas (1963) and Uttar Phalguni (1963) which were produced by Uttam Kumar Films Pvt. Ltd. Interestingly enough, each of these films is based on a well-known work by doyens of literature: James Hilton’s Random Harvest (Harano Sur), Tarashankar Bandopadhyay (Saptapadi), Subodh Ghosh (Jatugriha), Saratchandra Chatterjee (Grihadaha), Shakespeare via Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar (Bhranti Bilas) and Nihar Ranjan Gupta (Uttar Phalguni).

It goes without saying that in both Harano Sur and Saptapadi it is Suchitra Sen who has the meatier role and in fact even preceded Uttam Kumar in the credit billing. Uttar Phalguni of course is an out-and-out Suchitra Sen vehicle with Uttam not even acting in the film. Arundhati Devi matches him scene-for-scene in Jatugriha (which was loosely remade as Ijaazat by Gulzar), providing a scintillating duel between two actors at the top of their game. And despite being an Uttam-Suchitra film, the characters in Grihadaha are not starry-eyed lovers in the way they are in the other films starring the two. There’s a great deal of complexity that underlines the relationship here and that goes against the box-office grain of their other outings together. Uttam Kumar gives a glimpse of his ability to set aside star egos, letting Pradip Kumar hog the limelight and walk away with the accolades in what is his finest hour as an actor. The only film here that does not quite work for me is Bhranti Bilas, and that I suspect owes a lot to Gulzar’s Angoor (1982), which beats Uttam Kumar’s original hollow when it comes to laughs.

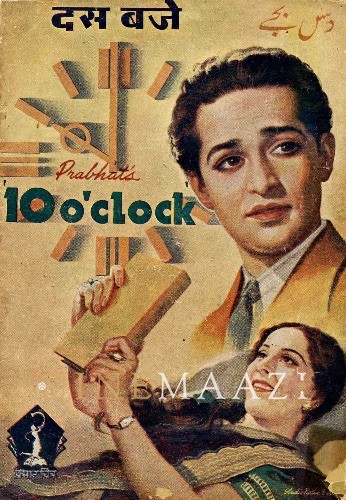

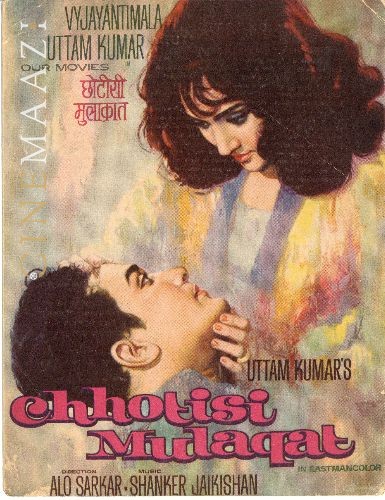

Unfortunately, the star could not bring his acumen as producer to his maiden Hindi venture, Chhoti Si Mulaqat (1967), which dealt a blow to his efforts at gaining a foothold in Bombay. Also, the vision that marked his stint as producer is lacking in the three films he directed: Shudu Ekti Bachhar (1966), Bonpalashir Padabali (1973) and Kalankini Kankabati (1981).

Shudhu Ekti Bachhar is the kind of romcom that Uttam Kumar should have done well in his sleep. And given that this was made at the peak of his powers as an actor, and after close to fifteen years in the industry, it is that much more of a disappointment. Written by the well-known lyricist Gauriprasanna Majumdar, the story must have looked good on paper. Bijayalakshmi Ray or Jaya (Supriya Devi) and Sanjay Chaudhuri (Uttam Kumar) are forced to go through a sham marriage for a year after their solicitors tell them that as per their respective grandfathers’ wills, they stand to lose all their property otherwise. Of course, with the two of them having rubbed each other the wrong way right at the start and given her haughty temperament, it is never going to be a smooth ride.

There are glimpses of a director’s vision in some of the sequences here, most notably the one where Udash tries to force himself on Padma, camouflaged among overgrown stalks and bushes. There are also some lovingly shot outdoors of rural Bengal which lend authenticity to the narrative. Despite the shortcomings, this one is a marked improvement over Shudhu Ekti Bachhar, with a string of strong performances (Supriya Devi, Bikash Ray, Nirmal Kumar, Jahar Ray, Anil Chatterjee, and in particular Basabi Nandi as Udash’s psychologically impaired wife). Uttam Kumar himself is a standout with his spot-on local dialect, particularly in the climactic sequences where, drunk, and losing his mind, he confronts Padma and the doctor.

The film stars Uttam Kumar as a dissolute zamindar (the kind he played to such perfection in Stree and Sanyasi Raja) who sets his eye on a courtesan Aparna (Sharmila Tagore, in a role I am sure she would like to forget). Though his wife (Supriya Devi) warns him that dalliances with courtesans have spelt ruin for the family for generations, it’s to no avail. Needless to say, Aparna falls in love with a courtier, leading to his murder and other atrocities being visited on her. Things take the expected turn when the zamindar’s son (Mithun Chakraborty) returns from his boarding school and promptly falls in love with Aparna’s daughter, who had been taken away from her mother and imprisoned by the zamindar. In an inexplicable and laughable casting decision, the daughter too is played by Sharmila Tagore and there’s never a moment you can visualize Mithun Chakraborty and Sharmila Tagore as lovers.

There’s nothing that redeems the film – not Uttam Kumar, not Supriya or Mithun, not Sharmila Tagore, despite the fact that she is named Aparna and there’s also a Nischindipur in the narrative! Kalankini Kankabati represents all that was bad about 1980s cinema – the kind of cinema Bengal would come to lament after the passing of the mahanayak. You know how bad the film is when one says that the only good thing about it is R.D. Burman’s music, incorporating two gems: Parveen Sultana’s ‘Bendhechhi beena’ (the tune was also used in Bemisaal’s Lata Mangeshkar solo, ‘Ai ri pawan’) and that college favourite of the era ‘Adho alo chhayate’.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)