Rajesh Khanna Via Bengal

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Over his glorious career as the first superstar of Hindi cinema, Rajesh Khanna worked in a number of films inspired by Bengali classics. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at some of these outings – good, bad and indifferent…

One of the features that defined Rajesh Khanna’s superstardom in the early 1970s is his work in a series of remakes of Bengali hits of the 1950s and ’60s. A number of these cast him in the character of a ‘social orphan deprived of maternal love and stricken by some existential malaise … who laughs to cover up some internal tragedy’ (Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen in Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema). Driving this was the presence of a number of stalwarts behind the camera who had their origins in the Bengali film industry before moving to Bombay in the 1950s who time and again dipped into classic Bengali films as sources of inspiration. Unlike Dilip Kumar, whose brand of tragedy involved plumbing the depths of despair that held little hope for the human condition, the Rajesh Khanna variety always nurtured the possibility of the silver lining.

Though some of the later remakes fail to measure up to the standards of the ones he was part of during his peak, the films offer an interesting insight into both Bengali films of the 1950s and ’60s and the career graph of a Hindi film star who epitomized the Bengali bhadralok like no one else.

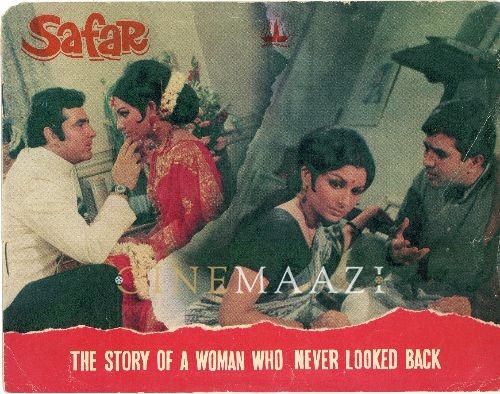

Khamoshi (1970) / Safar (1970) (Deep Jweley Jai [1959] / Chalachal [1956])

There’s a reason to look at Khamoshi and Safar together, apart from the fact that both were directed by Asit Sen. Both films have as their protagonist a woman – a nurse (Waheeda Rehman) in the former and a doctor/surgeon (Sharmila Tagore) in the latter. It says something about Rajesh Khanna’s superstardom that a number of his films at the time (Kati Patang and Amar Prem, for example) are essentially women-centric, with him playing an important supporting role.

There is no doubt that few stars in Hindi cinema have conveyed the dichotomy of life and death as well as Khanna did in Safar and Anand, and Rajesh Khanna is in top form in Safar. But I for one feel that in shifting the focus from Neela and in the change from black and white to colour (just compare the sequences featuring Neela and Avinash silhouetted against the Ganga ghat to the accompaniment of the song ‘Bhai re’ in Chalachal to a similar one in Safar, featuring Manna Dey’s mellifluous ‘Nadiya chale chale re dhara’), Safar loses out on the psychological underpinnings of Chalachal.

Amar Prem (1972) / Nishi Padma (1970)

Based on Bibhutibhushan’s short story ‘Hinger Kochuri’, Nishi Padma, directed by Aravinda Mukherjee, is often cited as the definitive Uttam Kumar performance after Satyajit Ray’s Nayak. The film is also noteworthy for Sabitri Chatterjee, who acted in a number of films opposite Uttam, matching the legend step for step, and for its evergreen Manna Dey songs, ‘Na na aaj ratey aar jatra dekhte jabo na’ and ‘Ja khushi ora boley boluk’ which won the film one of its two national awards (for best male playback singer).

Directed by Shakti Samanta, Amar Prem remains one of Rajesh Khanna’s, and indeed Hindi cinema’s, most celebrated performances as he does full justice to the character of Anand Babu, a businessman trapped in a bad marriage who finds love in the company of Pushpa (Sharmila Tagore) who sings at a brothel. Running parallel to their relationship is that of Pushpa’s with Nandu, an orphan in the neighbourhood who is ill-treated by his stepmother and for whom Pushpa becomes a surrogate mother. For all the histrionic heights Rajesh Khanna scales here, albeit aided by one of Hindi cinema’s greatest soundtracks, he had no qualms in admitting that he was not a patch on Uttam Kumar in Nishi Padma, in particular the way Uttam calls out to his ‘Pushpa’. And that climactic scene, set against the backdrop of Durga Puja, where the man who ‘hates tears’ is left moist-eyed, is guaranteed to move the hardest of hearts.

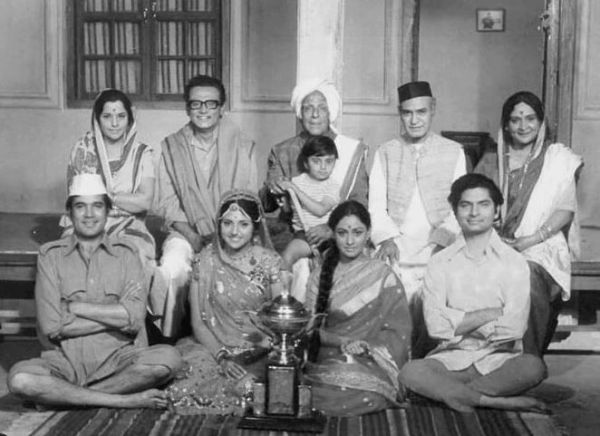

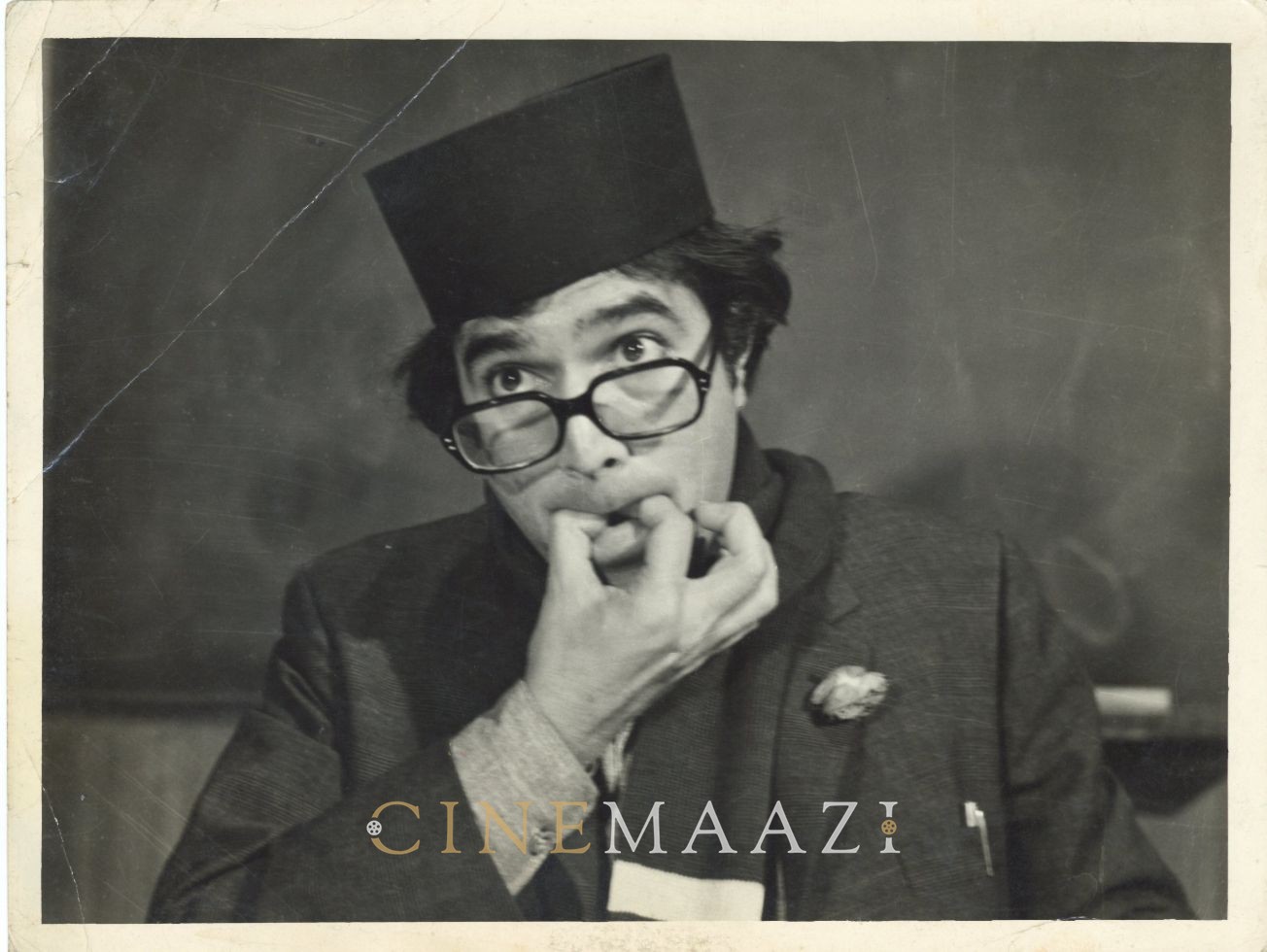

Bawarchi (1972) / Golpo Holeo Sotti (1966)

In-between art-house heavyweights like Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak on one hand and mainstream stalwarts such as Ajoy Kar, Asit Sen and Tarun Majumdar on the other, the works of Tapan Sinha, who managed a rare fusion between the artistically fulfilling and the commercially viable, are often overlooked. Golpo Holeo Sotti, based on a story the filmmaker himself wrote, offers an insight into the range the director was capable of – a comic fable in an oeuvre filled with glittering literary adaptations, swashbuckling adventures, children’s films and incisive socio-political commentaries. In a film that had a glittering galaxy of some of the finest character actors of Bengali cinema – including Chhaya Devi, Bharati Devi and Bhanu Bandopadhyay – Tapan Sinha made a coup of sorts casting Rabi Ghosh, so far seen primarily as a comic sidekick, as the protagonist Dhananjoy who arrives as a cook and manservant to set a dysfunctional family in order. And what a delight it is to watch two of Bengal’s greatest character and comic actors, Rabi Ghosh (who even gets to sing ‘Ka tabo kanto’) and Bhanu Bandopadhyay, feeding off each other in the two sequences they have together. Even in the comic-fable mould, the director weaves in satirical social and political statement through his characters discussing the food famine of the time, the imports of US wheat and the rise of the left (maidservants becoming aware of their rights and forming unions).

Like the original, Bawarchi too boasts of a stellar supporting cast, including A.K. Hangal, Kali Banerjee, Asrani, Dina Pathak, Usha Kiron, Jaya Bhaduri and Harindranath Chattopadhyay who is a scream as the family patriarch. The one aspect of the film that tops the original is the soundtrack composed by Madan Mohan and written by Kaifi Azmi, highlighted by Manna Dey’s ‘Tum bin jeevan’ and that ten-minute crazy medley ‘Bhor aayi gaya andhiyaara’.

Anurodh (1977) / Deya Neya (1963)

Uttam Kumar could charm your pants off when it came to light-hearted romcoms and Deya Neya is a prime example. Just watch him call out to his house help Gadai, ‘Oray Gadai, oray Godai’ (to the tune of the kirtan ‘Rai jago’) or engage in banter with his friend Asim (Tarun Kumar) and his wife (played by Lily Chakravarty) while trying to pat down a stray strand of hair on his head… He plays Prasanta Ray, an aspiring singer, in conflict with his businessman father B.K. Ray (Kamal Mitra). Forced to leave home after one such confrontation, Prasanta arrives in Kolkata and begins a career as a singer going by the name of Abhijit Chaudhuri who popularizes the songs of his ill and impoverished friend Sukanta. Circumstances play out so that he finds himself working as a driver called Hriday Haran at the household of eccentric rich man Amritalal (Pahadi Sanyal) and his headstrong niece Sucharita (Tanuja), who happens to be a fan of Abhijit Chaudhuri. With three identities to juggle, the character has his hands full and Uttam Kumar, the actor, delivers with aplomb in what is a triumph of Uttam Kumar, the star. In this endeavour, he is helped by what is one of the great soundtracks of Bengali cinema, featuring classics like ‘Jiban khatar prati pataye’, ‘Ami cheye cheye dekhi’, ‘Dole dodul’ and ‘Gaane bhuban’ (lyrics by Gauriprasanna Majumdar, music by Shyamal Mitra, who also produced the film and lent his voice to the songs).

Prem Bandhan (1979) / Harano Sur (1957)

Along with Saptapadi (1961), Harano Sur epitomizes the quintessential Uttam Kumar-Suchitra Sen melodrama, providing the template for their iconic on-screen pairing. Alok Mukherjee (Uttam Kumar) suffers a loss of memory after an accident. Dr Roma Banerjee (Suchitra Sen) rescues him and treats him in her father’s clinic in a village called Palaspur. They fall in love and marry but then a second accident restores the memory of his earlier life in Kolkata while wiping off all memory of Roma, who now takes up work as a governess at the Mukherjee household to help Alok remember their life together.

Though itself loosely based on the Hollywood film Random Harvest (1942), starring Ronald Colman and Greer Garson, Harano Sur’s Hindi remake starring Rajesh Khanna, Prem Bandhan, gives the phrase ‘loosely based’ a whole new connotation. The film opens with Rajesh Khanna washed up ashore and finding himself in the middle of a tribal settlement. He has no memory of what has brought him here and is named Kishan by the local priest. Before long he falls in love with the belle of the community, Mahua (Rekha), and they marry. Soon thereafter he finds himself in the city. When he does not return, Mahua sets out to find him only to discover that Kishan is a businessman going by the name of Mohan Khanna and has no memory of Mahua. Moreover, he is engaged to be married to Meena Mehra (Moushumi Chatterjee).

Ramanand Sagar’s treatment of the tribal community is riddled with every Hindi film cliché – the language (Mahua using words like ‘daiyya’ and ‘tukur tukar dekhat rahe’, the way they dress and court, the garrulous sidekicks – apart from the incongruity of Santhals, primarily a hunting community, residing next to the sea and engaged in fishing. Rajesh Khanna was well past his prime and had by now become a caricature of the star he used to be, painfully apparent in both his avatars. And Ramanand Sagar’s ham-handed handling of the material, replete with every stereotype of ’70s Hindi cinema, does not help. Unless you are enamoured of watching a shirtless Khanna playing the naïve simpleton to a waterfall-drenched Rekha, the only redeeming feature of the film is Kishore Kumar’s soulful rendition of ‘Main teray pyar mein pagal’.

Shatru (1984) / Shatru (1986)

As far as Rajesh Khanna is concerned in this group, this film is kind of an outlier. One character that the star never quite mastered is that of the action hero – and there are fewer sights more discordant in Hindi cinema than Rajesh Khanna in a police uniform. It is also strange that he was signed on as the lead given that the director is Pramod Chakraborty, known for the quintessential ’70s Dharmendra potboilers like Jugnu and Azaad. Shatru is more in line with what the He Man was known for.

In a year that Satyajit Ray’s Ghare Baire, the Soumitra Chatterjee starrer Kony and Aparna Sen’s Paroma wowed critics, it was debutant Anjan Choudhury who took the Bengali industry by storm, wooing the masses with Shatru. The film marked a definite change of pace for Ranjit Mallick, known so far for his acting chops in Mrinal Sen’s Interview and Calcutta 71 and a series of romantic outings in the 1970s. Here he turns action hero as the no-nonsense Subhankar Sanyal who arrives as officer-in-charge at Haridevpur police outpost in Birbhum, taking on the corrupt fiefdom of local businessman Nishikanto Saha (Manoj Mitra), his henchman Abdul (Biplab Chatterjee), MLA Nihar Chaudhuri (Bikash Ray) and his son Babu (current superstar Prosenjit in an early two-bit role, getting thrashed by the police officer), and corrupt police officer Haradhan Bhattacharya (Anup Kumar). In the process he befriends an orphaned young boy, Chhotu, and a widow – both of whom owe their woes to Nishikanto.

Rajesh Khanna’s version, again an almost scene-for-scene remake of the Bengali original (with the addition of a few songs picturized on Raj Kiran who plays the spoilt son of the MLA), came a cropper at the box-office, which isn’t surprising. Whatever was a novelty for the Bengali film – the mofussil ambience, an honest police officer against a system, the gallery of rogues, colourful dialogues – had been done to death in Hindi. So, what works in the Bengali, say, for example, the MLA’s son telling the police officer, ‘Who would have dared to mess with me if I could brandish a revolver like you?’, leading the officer to throw away the revolver and take on the rowdy, or the officer asking the MLA to seek permission before entering his room at the police station, only invites comparison with situations done infinitely better starting with Zanjeer.

Despite the Hindi version being emblazoned with a dedication 'to the PM Rajiv Gandhi’s crusade against red-tapism, favouritism and corruption’ – the star was at the time prominent in politics as a Congress leader – nothing can undo the miscasting of Khanna in the lead and the basic drawback of a story whose time had gone.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)