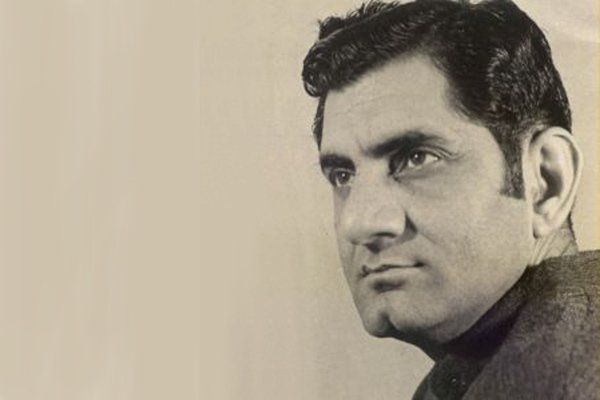

Anand Bakshi: The Everyday Philosopher

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

With over 3000 songs in more than 600 films, Anand Bakshi is arguably the most prolific songwriter in the history of Hindi films. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri pays a tribute to the finest of what he calls the ‘philosophical’ songs of this iconic lyricist.

Achha toh hum chalte hain … Bye-bye miss good night kal phir milenge … Ilu ilu … the list goes on … Arguably, no other lyricist in Hindi cinema can boast of as many songs that have become everyday catchphrases, lending them to titles of TV serials and web series and new films. But then Anand Bakshi was no ordinary songwriter. He was a master of the anthem, the connoisseur of the quotidian. If ‘Yeh dosti hum nahin todenge’ (Sholay, 1975) became the quintessential song celebrating friendship, ‘Dum maro dum’ (Hare Rama Hare Krishna, 1970) caught the zeitgeist of an impatient generation with its nihilist undertones, while few songs probably capture the yearning for the motherland as evocatively as ‘Chitthi aayi hai’ (Naam, 1986) does.

Then there is his mastery of the love song – the heartbreak in ‘Wo tere pyar ka gham’ (My Love, 1970), the wistfulness that informs ‘Pyar diwana hota hai’ (Kati Patang, 1971) or the sheer agony/ecstasy of ‘Yeh dil, diwana’ (Pardes, 1997). Anand Bakshi was the go-to lyricist for all teenage/youthful love stories, in particular those heralding a new star pair: from Bobby (1971) to Ek Duje ke Liye and Love Story (both 1981) to Hero (1983), his songs played the biggest role in the colossal hits these films became. No one probably articulates the longing of first love as well as he does with ‘Solah baras ki baali umar ko salaam’ in Ek Duje ke Liye. And if he was the voice of the times in the 1970s, with Jawani Diwani (1972), he was no less so as we approached the new millennium with ‘Tujhe dekha toh ye jaana sanam’ in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995).

No one could hold a torch to him when it came to the chartbusting item number either – ‘Dum maro dum’, ‘My name is Anthony Gonsalves’ (Amar Akbar Anthony, 1977), ‘Om shanti om’ (Karz, 1980), ‘Jumma chumma de de’ (Hum, 1991), ‘Choli ke pichhe kya hai’ (Khalnayak, 1993) and ‘Tu cheez badi hai mast mast’ (Mohra, 1994) to name just a few. Though the last three songs copped some criticism for lapse in taste, it has to be borne in mind that, one, here is someone with over 3300 songs in 600+ films in a career spanning close to five decades, and, two, someone who is purely a songwriter (one who does not have the luxury of directing the film or writing it, like some of his eminent contemporaries have) asked to deliver a song as per the situation conceived by the director and/or writer.

In all the hosannas heaped on him for his ability to churn out chartbusters and all the barbs directed at him for his ‘simple’ verse, there’s a whole segment of Anand Bakshi songs that advocate a certain philosophical take on life that are not recognized as such. Many a Hindi film lyricist’s songs have been quoted in the context of the ‘metaphysical’ statement they make – and it is true that the Hindi film song at its best does speak of the highest philosophical thoughts of the poet and the character in the film.

However, though these Anand Bakshi songs figure among the finest in Hindi cinema, not much has been said about how beautifully each one conveys an attitude, an approach to life. Maybe it’s because these words speak of life’s truth in the simplest of language, one that is accessible to everyone. Above all, though all of these are set to certain specific situations in a film, take them out of their cinematic contexts and they still ring true.

‘Yahan main ajnabi hoon’, Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965)

This is the film that launched Anand Bakshi into the big league, with each song a chartbuster. I remember watching it at a theatre in the mid-1980s when a number of old hits were rereleased in the absence of new films. One moment still stands out in memory: the whole hall bursting out in applause as Shashi Kapoor lip-synced to the lines, in Mohammad Rafi’s tremulous timbre: ‘Main kaise bhool jaun / main hoon Hindustani’. In the line ‘main jo hoon bas wahi hoon’ you have the last word in being comfortable in your own skin. I am reminded of the universality of the line in the context of Popeye’s well-known statement: ‘I am what I am.’ The poet’s son, Rakesh Anand Bakshi, says: ‘The song was not written for the film, but the situation fit the film, so he added verses to suit the story. He wrote it from the humiliating experiences he had in Bombay during his first visit in 1950. He had felt like an alien and unwanted soul. He went back to the army and returned in 1956 to make it as a songwriter.’

‘Maajhi chal, o maajhi chal’, Aaya Sawan Jhoom Ke (1969)

‘Dum maro dum’, Hare Rama Hare Krishna (1971)

Just four lines, and yet what impactful ones they are. ‘Duniya ne humko diya kya / duniya se hamne liya kya / ham sabki parwah karein kyon / sabne hamara kiya kya.’ Even taken out of the drug-induced haze of the film’s protagonists, the lines speak of an attitude to life that everyone who has ever been young will vouch for. In what stands testimony to the astounding versatility of the poet, the very next year, Anand Bakshi would have another song espousing a similar thought but in words infused with lyricism of a different kind: ‘Kuch toh log kahenge / logon ka kaam hai kehna / kyun bekaar ki baton mein…’.

‘Chingari koi bhadke’, Amar Prem (1972)

‘Kuch toh log kahenge’, Amar Prem (1972)

‘Yeh jeevan hai is jeevan ka’, Piya ka Ghar (1972)

‘Gadi bula rahi hai’, Dost (1974)

Gadi ka naam

na kar badnam,

patri pe rakh ke sar ko

himmat na haar

kar intazaar

aa laut jaae ghar ko

ye raat jaa rahi hai

wo subah aa rahi hai

Rakesh adds that his father would often say, ‘I never really valued film industry awards after I received the biggest award ever that will travel with my soul after this journey on Earth. A man had written to me that the verse “Gadi ka naam na kar badnam” had prevented him from taking his own life under the wheels of a train that ran nearby his village in UP.’

There’s also an exhortation that echoes Swami Vivekananda’s ‘Arise awake and stop not till the goal is reached’, overcoming all obstacles with hope and determination:

Sun ye paigam

ye hai sangram

jeevan nahi hai sapna

dariyaa ko faand

parvat ko chir

kaam hai ye uskaa apna

ninde udaa rahi hai

jaago jaga rahi hai

‘Aadmi musafir hai aata hai jata hai’, Apnapan (1977)

‘Zindagi ke safar mein guzar jaate hain jo makaam’, Aap Ki Kasam (1974)

‘Seesha ho ya dil ho aakhir toot jata hai’, Aasha (1980)

No wonder in the forthcoming biography of Anand Bakshi, Nagme Kisse Baatein Yaadein, penned by Rakesh, Javed Akhtar says, ‘One day, people will realize Anand Bakshi’s contribution to Hindi cinema and to our literature. Upon this realization, universities will offer PhDs on his lyrics.’

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)