‘A bottle in one pocket, your childhood in the other’: Ritwik Ghatak’s Bombay–Poona years

19 Dec, 2019 | Stories by Shamya Dasgupta

‘I think Ghatak became a thing more than a person. A myth. A sort of ghost that, through its continuous presence, egged people on to keep thinking, thinking creatively.’

In his short stint at the FTII, Ritwik Ghatak influenced a whole generation of student film-makers … Shamya Dasgupta revisits the maverick director’s avatar as a teacher

‘When I go to the film institute now, there are so many ghosts floating around. There’s Antonioni, there’s Kurosawa, Tarkovsky; the biggest of them Ritwik-da, Ritwik-da is always there.’

Saeed Mirza, in his mid-seventies now, is understandably a bit sentimental as he thinks back to the Ritwik Ghatak he knew only for a month or two as a student, when Ghatak was teaching at Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Poona (now Pune). Those weeks spent together, Mirza has always said, left a lasting impact on him.

So, what is this ghost then? Is Ghatak, the self-destructive wastrel-genius, still relevant? Even now, when Gajendra Chauhan, B.P. Singh and the like are at the helm of affairs at FTII?

‘Ghatak’s presence was palpable. No denying that,’ says Arjun Gourisaria, an editor and director who studied at FTII in the mid-1980s. ‘As we got into the campus, the ragging initially was very different, almost semi-intellectual. I would be walking and someone would say, ‘Zameen pe nazar rakhke chal, yahan Ghatak chala karta tha [Keep your eyes on the ground, Ghatak used to walk here].’

Students from the 1980s and 1990s recall stories about the man, some true, many likely apocryphal; Ghatak was eminently story-worthy, wasn’t he? Gourisaria recalls, ‘He would, apparently, come for screenings inebriated, and if there was a particularly well-made sequence, he would make a very loud noise. It was to tell students to take note of the moment.’

That’s a telling story, for, as Gourisaria says, ‘I think Ghatak became a thing more than a person. A myth. A sort of ghost that, through its continuous presence, egged people on to keep thinking, thinking creatively.’

‘Bhabo, bhabo, bhaba practice koro [Think, think, train yourself to think],’ Ghatak is reported to have said – by all accounts, it sounds like him.

*

'I heard from Salil that [Sashadhar] Mukherjee is upset about not being able to meet me in Calcutta...Truth be told, there is no work at all, I just have to write a bit of rubbish once in a way and go sit in office from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.’

By the mid-1950s, Ghatak was a disillusioned man. Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali had released to much acclaim as, arguably, the first all-muscle arthouse Indian film. But Ghatak had made Nagarik in 1952 – it ought to have been that ‘first’. Except that it hadn’t released then because of distribution and other issues. (It did later, after Ghatak’s death in 1976).

Then, in late 1955, he was expelled from the Communist Party of India (CPI). Ghatak said that his colleagues had branded him a Trotskyite, a permanent revolutionary. A letter to him (dated 21 October 1955), after he attended a party commission of inquiry, simply said that the party had decided to ‘remove your name from the rolls where it had crept in by mistake’.

By then, Ghatak had shifted to Bombay (now Mumbai). He was living in a small flat in Goregaon, and had a writing job with Filmistan, Sashadhar Mukherjee’s iconic studio set-up. Before setting up in his own flat, Ghatak had lived with Hrishikesh Mukherjee in Andheri for a while. Letters between Ghatak and his wife Surama – published in book form not too long ago – talk about Keshto Mukherjee living with them for a while, evenings with Salil Chowdhury, Bimal Roy’s house being close by, watching the shooting of Devdas (released the same year), and trying to make a living.

How did it go for Ghatak in Bombay? And then in Poona? Indeed, for a man as reputed for his alcoholism and erratic ways as he was for his movie-making, how did the job with FTII happen in the mid-1960s? And what did he actually achieve in Poona, how did he become the biggest of the ghosts?

The letters published by Surama Ghatak paint a picture of hope in Bombay – of trying to do a spot of decent work and earning money so he could try and do better work in cinema and in theatre. But we also see a restless man, out of his depth in a city and a work milieu he doesn’t quite understand. Calcutta (now Kolkata) is where he wants to be, where he feels at home in the world.

Soon after reaching Bombay, perhaps while still living with Hrishikesh Mukherjee, he writes on 30 June 1955: ‘I heard from Salil that [Sashadhar] Mukherjee is upset about not being able to meet me in Calcutta. He told Salil that I am going to be useless for the next year because of my marriage, and that he has made a mistake by offering me the job. Be that as it may, I met him yesterday and after saying this and that, I joined work officially. But it’s upsetting when I see the way they work. Truth be told, there is no work at all, I just have to write a bit of rubbish once in a way and go sit in office from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.’

Everything is fine at this stage, but with the benefit of hindsight, it is wrenching, because we see where this will go.

In the same letter: ‘I just have to grit my teeth and keep trying to earn some money. I don’t know if I’ll be successful, but nothing else is possible here. Doing good work, doing my kind of work, showing what I am capable of and trying to establish myself, all of that looks out of reach right now. I just have to find a way to earn a monthly salary.’

And then: ‘Look, Lakshmi (possibly a nickname for his wife), this life is not for us. Working for money is not something I have done before, and it’s disgusting to me. Somehow, if I can pay off my debt of around Rs 1000 and be in a position to pay Bhupati [not clear who] a hundred rupees a month for a year or so, I will leave all this. This can’t go on. I look around me and see that even people who earn three or four thousand rupees a month are not happy. But I have found peace in doing the kind of work I like without earning so much as a paisa.’

Ghatak concludes that he will continue to do his kind of work – writing scripts, plays, and even a novel in the time with Filmistan – while doing the ten-to-five routine. And then leave. To go to Calcutta and ‘earn three-four hundred rupees a month between the two of us’, which, he writes, would give them ‘swargashukh’, it would be their utopia.

That doesn’t happen right away, of course. Surama visits him from time to time but has a teaching job in Shillong to return to. And Ghatak struggles to impress his bosses. He isn’t Bombay enough. And his stories don’t excite Filmistan.

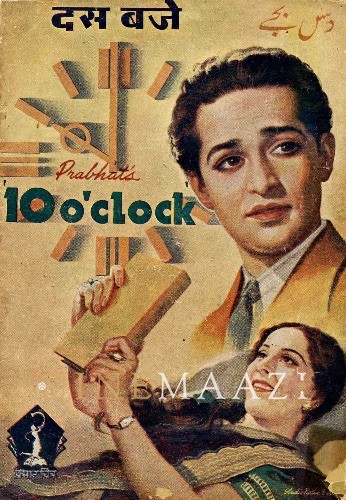

Bimal-da has promised to buy his story and produce a film as part of Bimal Roy Productions, he writes one day. What story was it? Did Roy buy it? We can’t be sure, but it might have been Madhumati. The film, based on ‘Ritwick’ Ghatak’s story, released in 1958. Before that, in 1957, ‘Hrishikes’ Mukherjee made his first film, Musafir, with Ghatak credited for the script.

At some stage, we learn from letters to his wife, this happened too: ‘I have planned a story for Filmistan. I like it very much. An atomic research scientist falls asleep while doing his research, dreaming about a future world where a universal scientific community has taken shape. Of course, I have to keep space for a lot of song and dance and romance, and melodrama; I have to put in all the ingredients of a Bombay film. But, despite that, I think I can focus on scientific development and social structure and psychological evolution, and still make it an entertaining story. I will ask Dr Meghnad Saha [the astrophysicist] for help when I come back home during [Durga] Pujo. We can ask the Nuclear Physics Laboratory here for help too. Sashadhar Mukherjee wants to hear the story the day after tomorrow. If he likes it, I can start thinking about doing some good work.’

Sashadhar Mukherjee didn’t like the story. ‘He wants something more Bombay-type.’

So it went, in ‘this rotten, commercialised city’, with rare specks of sunshine: ‘Mrinal Sen [the film director, an old friend] and Samaresh Basu [the author] are here for work. I am having a wonderful time chatting with Mrinal.’ All the while Calcutta remains impossible: ‘Thinking about escaping from here makes me happy, but when I think about the financial situation in Calcutta, I take a step back.’

In March 1957, the Ghataks were back in Calcutta. In April 1956, when Sashadhar Mukherjee was recovering from a bout of ill-health, Ghatak wrote a most respectful but rather naïve letter to the veteran producer, imploring him to provide space for experimental film-making.

‘… Approach of naïve hypocrisy and pandering to the baser instincts of men alone is not always enough to-day for delivering the goods,’ Ghatak wrote. Sashadhar Mukherjee was a mainstream film producer. Period. He made excellent films, like Paying Guest, Dil Deke Dekho, Ek Musafir Ek Hasina. Ghatak’s plea to ‘create a corner where new facts can be made’, even if it appealed to him, would never have made commercial sense to the man. We don’t know of their discussion on the matter, if any, but no such space was ever created. Not long after, Ghatak’s Filmistan stint came to an end, even as Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Salil Chowdhury and his other friends continued to make hay as the sun shone across the Arabian Sea.

Then, in late 1955, he was expelled from the Communist Party of India (CPI). Ghatak said that his colleagues had branded him a Trotskyite, a permanent revolutionary. A letter to him (dated 21 October 1955), after he attended a party commission of inquiry, simply said that the party had decided to ‘remove your name from the rolls where it had crept in by mistake’.

By then, Ghatak had shifted to Bombay (now Mumbai). He was living in a small flat in Goregaon, and had a writing job with Filmistan, Sashadhar Mukherjee’s iconic studio set-up. Before setting up in his own flat, Ghatak had lived with Hrishikesh Mukherjee in Andheri for a while. Letters between Ghatak and his wife Surama – published in book form not too long ago – talk about Keshto Mukherjee living with them for a while, evenings with Salil Chowdhury, Bimal Roy’s house being close by, watching the shooting of Devdas (released the same year), and trying to make a living.

How did it go for Ghatak in Bombay? And then in Poona? Indeed, for a man as reputed for his alcoholism and erratic ways as he was for his movie-making, how did the job with FTII happen in the mid-1960s? And what did he actually achieve in Poona, how did he become the biggest of the ghosts?

The letters published by Surama Ghatak paint a picture of hope in Bombay – of trying to do a spot of decent work and earning money so he could try and do better work in cinema and in theatre. But we also see a restless man, out of his depth in a city and a work milieu he doesn’t quite understand. Calcutta (now Kolkata) is where he wants to be, where he feels at home in the world.

Soon after reaching Bombay, perhaps while still living with Hrishikesh Mukherjee, he writes on 30 June 1955: ‘I heard from Salil that [Sashadhar] Mukherjee is upset about not being able to meet me in Calcutta. He told Salil that I am going to be useless for the next year because of my marriage, and that he has made a mistake by offering me the job. Be that as it may, I met him yesterday and after saying this and that, I joined work officially. But it’s upsetting when I see the way they work. Truth be told, there is no work at all, I just have to write a bit of rubbish once in a way and go sit in office from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.’

Everything is fine at this stage, but with the benefit of hindsight, it is wrenching, because we see where this will go.

In the same letter: ‘I just have to grit my teeth and keep trying to earn some money. I don’t know if I’ll be successful, but nothing else is possible here. Doing good work, doing my kind of work, showing what I am capable of and trying to establish myself, all of that looks out of reach right now. I just have to find a way to earn a monthly salary.’

And then: ‘Look, Lakshmi (possibly a nickname for his wife), this life is not for us. Working for money is not something I have done before, and it’s disgusting to me. Somehow, if I can pay off my debt of around Rs 1000 and be in a position to pay Bhupati [not clear who] a hundred rupees a month for a year or so, I will leave all this. This can’t go on. I look around me and see that even people who earn three or four thousand rupees a month are not happy. But I have found peace in doing the kind of work I like without earning so much as a paisa.’

Ghatak concludes that he will continue to do his kind of work – writing scripts, plays, and even a novel in the time with Filmistan – while doing the ten-to-five routine. And then leave. To go to Calcutta and ‘earn three-four hundred rupees a month between the two of us’, which, he writes, would give them ‘swargashukh’, it would be their utopia.

That doesn’t happen right away, of course. Surama visits him from time to time but has a teaching job in Shillong to return to. And Ghatak struggles to impress his bosses. He isn’t Bombay enough. And his stories don’t excite Filmistan.

Bimal-da has promised to buy his story and produce a film as part of Bimal Roy Productions, he writes one day. What story was it? Did Roy buy it? We can’t be sure, but it might have been Madhumati. The film, based on ‘Ritwick’ Ghatak’s story, released in 1958. Before that, in 1957, ‘Hrishikes’ Mukherjee made his first film, Musafir, with Ghatak credited for the script.

At some stage, we learn from letters to his wife, this happened too: ‘I have planned a story for Filmistan. I like it very much. An atomic research scientist falls asleep while doing his research, dreaming about a future world where a universal scientific community has taken shape. Of course, I have to keep space for a lot of song and dance and romance, and melodrama; I have to put in all the ingredients of a Bombay film. But, despite that, I think I can focus on scientific development and social structure and psychological evolution, and still make it an entertaining story. I will ask Dr Meghnad Saha [the astrophysicist] for help when I come back home during [Durga] Pujo. We can ask the Nuclear Physics Laboratory here for help too. Sashadhar Mukherjee wants to hear the story the day after tomorrow. If he likes it, I can start thinking about doing some good work.’

Sashadhar Mukherjee didn’t like the story. ‘He wants something more Bombay-type.’

So it went, in ‘this rotten, commercialised city’, with rare specks of sunshine: ‘Mrinal Sen [the film director, an old friend] and Samaresh Basu [the author] are here for work. I am having a wonderful time chatting with Mrinal.’ All the while Calcutta remains impossible: ‘Thinking about escaping from here makes me happy, but when I think about the financial situation in Calcutta, I take a step back.’

In March 1957, the Ghataks were back in Calcutta. In April 1956, when Sashadhar Mukherjee was recovering from a bout of ill-health, Ghatak wrote a most respectful but rather naïve letter to the veteran producer, imploring him to provide space for experimental film-making.

‘… Approach of naïve hypocrisy and pandering to the baser instincts of men alone is not always enough to-day for delivering the goods,’ Ghatak wrote. Sashadhar Mukherjee was a mainstream film producer. Period. He made excellent films, like Paying Guest, Dil Deke Dekho, Ek Musafir Ek Hasina. Ghatak’s plea to ‘create a corner where new facts can be made’, even if it appealed to him, would never have made commercial sense to the man. We don’t know of their discussion on the matter, if any, but no such space was ever created. Not long after, Ghatak’s Filmistan stint came to an end, even as Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Salil Chowdhury and his other friends continued to make hay as the sun shone across the Arabian Sea.

*

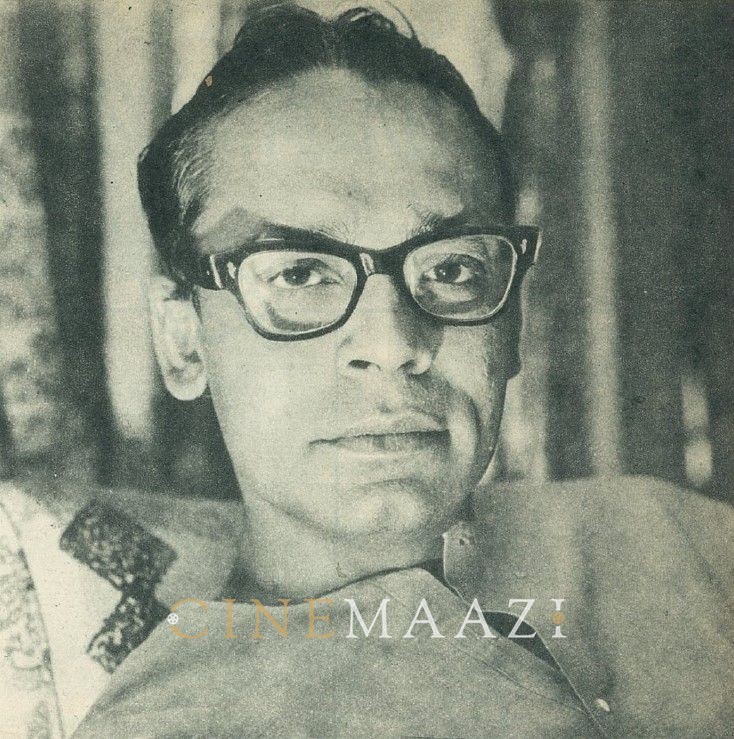

A rebel, a drunkard, totally irreverent; little of what Ghatak spoke of in his avatar as a teacher had to do with textbooks or theory. More than anything else, what he brought to the table was passion, the possibilities of cinema, a childlike enthusiasm for the medium – and storytelling.

Alcohol had become a close companion by then – it would become a constant in the not-too-distant future. Despite that, upon returning to Calcutta, Ghatak did some of his best work: Ajantrik (1958), Bari Theke Paliye (1958), Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komal Gandhar (1961), as well as a number of documentaries, some completed, some not.

Surama Ghatak writes: ‘Around the end of 1964, there were invites from the Poona film institute to go and give lectures. So he travelled to Poona once in a way. From the beginning of 1965, things started going wrong, in terms of his ways, he became more erratic. He did get the position in Poona nevertheless, and, up until that point, he did seriously try to get better, be better. He wrote that in his letters. And he was concerned about the children till that point.’

A rebel, a drunkard, totally irreverent; little of what Ghatak spoke of in his avatar as a teacher had to do with textbooks or theory. More than anything else, what he brought to the table was passion, the possibilities of cinema, a childlike enthusiasm for the medium – and storytelling. Mirza remembers a tale about Ghatak: Kundan Shah had asked him what one needed to be a good director, and our man answered, ‘A bottle in one pocket of your kurta, your childhood in the other.’ That was his mantra for a youngster trying to crack open the mysteries of cinema. Or was it just a cool line?

‘He used to talk about cinema in a manner that was more dreamlike, more than text and theory,’ Mirza says. ‘He gave us a sense that it’s an active creation, not just business. That gave us a sense of responsibility, when you attach your name to a piece of work, be careful, be sure.’

If you’re young and impressionable, what would it be like to meet a man like that?

For once, Ghatak liked his circumstances. In early 1965, he wrote home: ‘I am being looked after extremely well here, it might be the only place left where everyone is excited to have me.’

To start with, he was a visiting faculty, a guest lecturer. The position was a fair one, the compensation too, and he was getting respect. By then, he was no longer a moviemaker who couldn’t finish his films or fail to get them released; he had made what remains one of Indian cinema’s tours de force – Meghe Dhaka Tara, and though Subarnarekha was still some way away, Ajantrik and Komal Gandhar had made a mark too. He had arrived.

Ghatak was, at one point, offered a five-year contract at the institute and that brought about a sea change in his attitude towards Calcutta and, well, the outside. ‘I don’t like Calcutta any more either. I am getting respect here, a fixed salary, and the sort of work that I like. If I can join before the summer vacation, I might get a chance to go to Afghanistan for two months and work on an experimental film.’

But this is Ritwik Ghatak. So, sure enough, a few days later, another letter reaches Surama saying, ‘I feel claustrophobic here. I will feel better if I spend three days in Calcutta.’

And then the contract was signed – Ghatak was vice-principal/director at the Film and Television Institute of India. Not too long after that, he was with his wife in Shillong, having quit his job.

That period, short though it was, was significant, both personally and for the institute. Looking back, Ghatak called it ‘among the best days of my life’. The process of trying to become a teacher, then becoming one, attempting to mould youngsters in his own idealistic vision, winning them over … ‘it’s a different joy when you can mould many young people the way you want’.

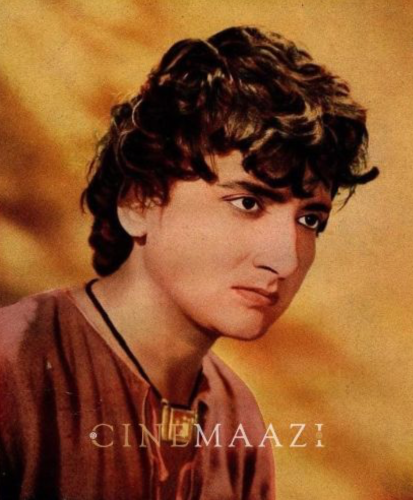

Among the many were Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, perhaps the two students most often associated with Ghatak’s time at FTII where, legend has it, he did most of his teaching sitting under the fabled Wisdom Tree. Very Santiniketan, some would say. Often drunk. That’s not terribly Santiniketan, of course.

Shahani, who was deeply influenced by Ghatak, recalls: ‘I met him the first time at a screening of Subarnarekha at Anandam Film Society in Bombay. This was before I went to FTII, or he had moved to FTII. He was hoping to get it released in Bombay, or elsewhere, because it had been taken out of the theatres in Calcutta almost immediately after it had released. He was sitting there, smoking a bidi, oblivious to the fact that the ash was falling on his rather crumpled kurta. He might have been drunk. He was very emotional, because we praised the film a lot. I was deeply moved by it, and he seemed to not believe what we were saying about the film. The Ritwik-da I came to know later was, if I may say so, quite arrogant. But not on that day.’

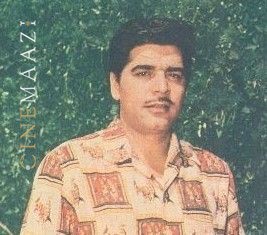

Mirza didn’t get as much time with Ghatak as Shahani did, but they agree on one important aspect of the man, his persona: the lack of organization, of discipline, of structure.

It is also the enduring image of Ritwik Ghatak – dishevelled, with a slightly crazed appearance. There are the stories of alcoholism and erratic behaviour, and more alcoholism, and then, in his later life, time at a mental asylum. A bit of genius too, of course.

‘Like many poets, while he had a lot to say, he had not the ability to organize, he wasn’t structured in his ways. By the time I met him, he had turned his back to Calcutta, though he missed the city and its people terribly. He was deeply disenchanted with his colleagues, his comrades,’ Shahani has written of his teacher.

Mirza elaborates, ‘Look at the stability in [Satyajit] Ray’s work. The strength and the rootedness. And then you come to Ghatak, and there’s disjointedness. Same between Adoor [Gopalakrishnan] and [G.] Aravindan. I don’t know what it is, maybe just the way our mind works … trying to figure out, not like a stable, structured mind.’

Maybe – who can be sure? – even that side of him was a consequence of the scars of Partition. The Partition of Bengal, twice over at that, was a key element in his art. Rootlessness, the plight of the refugee, the sense of un-belonging, the deep gashing wound so many of us carried for so long, and some of us continue to…

So many artists made profound art around the theme of Partition. With Ghatak, it ran deep. He wore the wound on his dirty kurta sleeve, on his often-broken glasses, his bottle of cheap alcohol … in his words, in his life.

‘With him, it was so apparent, there is a mentality of the refugee, which ran through his work. There was no stability in it, no strong roots. Some artists create work which has rock-solid foundations, you know; his work was more … ephemeral. It was unstable. But that gave it a kind of dynamism. It spoke to you,’ Mirza says. ‘And the man himself seemed not rooted. It’s very difficult to explain. My work is also not rooted, I suppose. So there’s an ongoing search to figure out roots, establish roots too.’

*

So many of the legends of Indian cinema have taken classes at FTII, shaping the worldviews and careers of the many students that go there hoping to find a direction, a calling. Ghatak spent barely any time at the institute. Was he asked to leave? His letters suggest he resigned. One way or the other, few others became icons as Ghatak did in such short span of time, with his bottle and his childhood. Mythical almost.

‘Discussing shot breakdown, someone would say, ‘Oh, you should use a wide-angle lens, haven’t you seen Meghe Dhaka Tara’ – so many such stories,’ Gourisaria remembers. ‘A sense that he was one of us … he’s from the same campus, he would sleep under the same tree, drunk, as we did. Like a mythical being almost…’

......................................

94 views

Tags

About the Author

Shamya Dasgupta works with ESPNcricinfo in Bengaluru, and is the author of Don't Disturb the Dead - the Story of the Ramsay Brothers.

.jpg)