Eccentrics, Their Victims and Absurdist Free Verse: The Comic Genius of Jandhyala

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

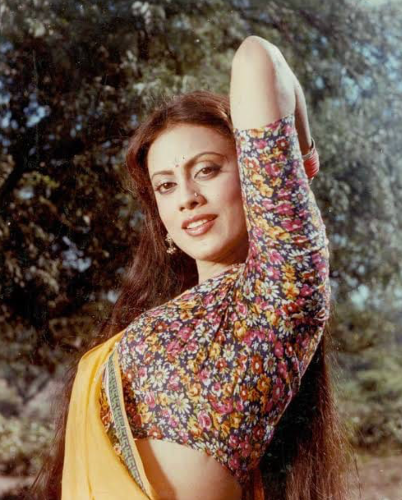

Till my late teens, thanks to my father’s elitist gene, his library of American film books and his unremitting tales of the Golden Age, I grew up hating Telugu (and Tamil and Hindi) films because, hey, what better way to love Hollywood? Even movies that featured my grandfather’s (poet and lyricist Devulapalli Krishna Sastri) songs, I went to only if the projections were in the day. So I could bunk school. Or if they featured this upcoming young actress, the only non-white girl I was willing to lease out my heart to on a Friday-to-Friday basis, Jaya Prada.

Had I actually been reading the title cards of the few movies I did go to in the 1970s, I may have recalled that the man who brought me to see Telugu films in the ’80s had one of his first significant credits as dialogue writer in a Jaya Prada starrer, Siri Siri Muvva (1976), K. Viswanath’s acclaimed dance film, a kind of a precursor to his best-known work, Sankarabharanam (1980). (Siri Siri Muvva was later remade in Hindi as Sargam.)

Flash forward to the early 1990s. I was at a social event, chatting with Jandhyala. I was now a bona fide admirer of his work and had seen all his films.

‘When I was just a dialogue writer for films, I met your grandfather,’ he said to me. ‘Realizing I had directorial aspirations, he wrote just this one thing for me on his scribbling pad: If you are going to be a director, tell it like K. Viswanath, show it like Bapu. I still have that piece of paper with me. I think it’s the best piece of advice I’ve got.’

(My grandfather lost his voice to cancer in the mid-1960s. In the latter part of his life, all his communication was via scribbling pads.) Whether Jandhyala took this tip seriously or not I can’t say, but he single-handedly got me watching Telugu films. As for discovering Jandhyala, I owe it to a filmi friendship, one with a young leading man who had recently made his celluloid debut, who dragged me to a film called Srivariki Premalekha (1984). ‘It’s a comedy, ra,’ he said. ‘You’ll like it.’ I went mainly because I knew there would be Old Monk and Campa Cola later. And it would be his treat.

I don’t remember if we had a drink that night but I will not forget that night. I couldn’t remember laughing that hard at a movie, that, too, a Telugu one.

‘Is there a show again tomorrow? I missed half the jokes because I was laughing at the previous ones,’ I remember asking.

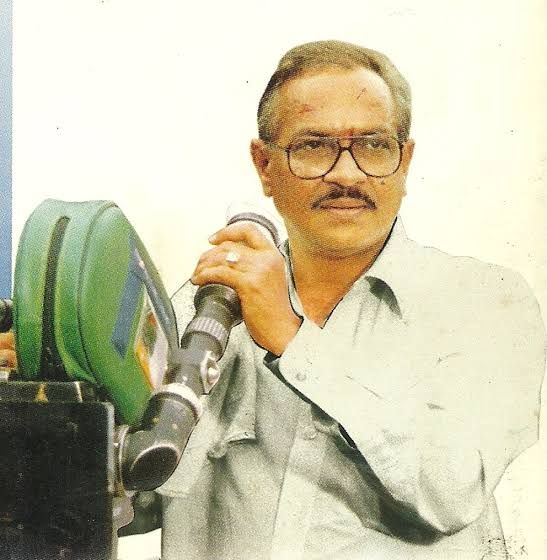

Other than the fact that Jandhyala was a prize-winning playwright in college, had furnished the dialogue for over 200 films, wrote for both NTR–Raghavendra Rao potboilers like Adavi Ramudu (1977) and K. Viswanath classics like Sankarabharanam with equal felicity, and came to be called Haasya Brahma, surprisingly little is available about him for the English reader.

‘What crisp, witty, inventive dialogue, so steeped in Telugutanam/Genuine clean fare, ideal for the entire family, they don’t make them like that any more/So identifiable, so middle-class/No better cure for the blues.’

All true.

However, Jandhyala’s greatest comedic contribution to Telugu films, his signature set-up, was that of The Eccentric and His Victim. No film of his was complete without this nativized Punch-and-Judy combination. In fact, quite often, it looked like the lead pair, the story, the songs and even the plot in his films were mere speed-bumps negotiated en route to highlighting as many human foibles as he could, and the limits he could push said peculiarities through supporting characters.

Let’s begin with the ‘eccentric’ from his most popular film, the one Kota Srinivasa Rao played in his biggest hit, Aha Naa-Pellanta! (1986). Lakshmipathy’s (Srinivasarao) ‘idiosyncrasy’ in this film is his extreme miserliness. And his main ‘victim’ is his hapless Man Friday, Govindu AKA ‘Ara Gundu’, played by Brahmanandam in an unforgettable performance in his first major role. Every imagined misdemeanour of his employee’s is met with a brutal pay-cut by Lakshmipathy, till Ara Gundu ends up having to pay to work for his master.

To me, the defining scene in this movie, featuring the summit of Lakshmipathy’s niggardliness, is when he’s put in the rare position of having to feed his brother-in-law; in other words, the legendary miser faces his ultimate horror: an unforeseen, unnecessary outlay. Lakshmipathy makes the relative eat plain rice while staring at a live chicken hung from the ceiling, telling him it’s the same as eating chicken curry and rice. (Notice the nod to the Akbar–Birbal story here.)

Then comes the reaction of the brother-in-law, played by Veerabhadra Rao (a Jandhyala staple who mostly played the eccentric, not the victim). In true Jandhyala style, the victim’s reaction is twice as extreme as his tormentor’s eccentricity.

Veerabhadra Rao is so disturbed by his brother-in-law’s profound meanness that his brain melts and he regresses into a past life. Real or imagined doesn’t matter. As he gently fondles the live chicken that he has freed, Veerabhadra Rao recalls his life as a king via an outrageous monologue featuring, among other things, the British, unpaid taxes, and his horse developing an elephant’s trunk and climbing the wall like a lizard. It is a master class in absurdist free verse. Sanity is restored a few minutes later by Ara Gundu dousing the victim with a bucket of cold water.

Jandhyala’s favourite ‘extremists’ were Sri Lakshmi and Veerabhadra Rao. In various Jandhyala vehicles, the mild-mannered Sri Lakshmi portrayed a series of memorable eccentrics. In Srivariki Premalekha, she is a compulsive reteller of film stories – from opening title card to the ‘Jana Gana Mana’ played at the end of the movie – verbatim, with background score and songs. In Chantabbai (1986), she is a poet of incomprehensible verse with mystifying titles like Akupachcha Kanneeru and Mettani Gundurayi, systematically hounding out the slowly disintegrating editor of a women’s magazine. In yet another film, she is the inveterate chef of bizarre dishes with names like Bangala Bhow Bhow, tirelessly trying them out on her doomed husband. Then, a performer of unorthodox vratams with, again, her husband the victim of this unconventional religious persecution: the list goes on.

Jandhyala’s quintessential victims were Brahmanandam and Potti Prasad.

Brahmanandam’s reaction to Veerabhadra Rao’s ‘story narration’ can only be seen, not explained, in this scene from Vivaha Bhojanambu (1988) Don’t miss the framing of Rao and Brahmanandam in this scene. It is a Sergio Leonesque extreme close-up of the former’s face with the rest of the frame left free for Brahmanandam to do his extempore interpretation of befuddled anguish.

The underutilized, underrated Potti Prasad’s reaction to long-term verbal abuse from a foul-mouthed father-and-son duo, Kota Srinivasa Rao and Master Vinnakota Kiran, in Hai Hai Nayaka (1989), is subtler. As the teaching staff of the school, where the film is partially set, is deep in discussion, the ageing peon who has lost his bearings, is seen in the background, hanging dolefully from a branch like a khaki-clad sloth bear.

Jandhyala introduced a riot of comedians to the Telugu film industry. The first among them was the ‘Suthi Janta’: Suthi Velu and Suthi Veerabhadra Rao. In the ’80s, there wasn’t a film that didn’t feature these former theatre actors, and you couldn’t have a conversation in Telugu without the word ‘suthi’ popping up. (Suthi literally means hammer. Thanks to Jandhyala, for more than a decade, the original meaning of the word was all but forgotten, and for Telugus everywhere, it became a metaphor for nagging.)

Heroes Rajendra Prasad and Naresh did their best films with Jandhyala. Jandhyala didn’t just make comedy the most sought-after genre in Telugu films, with even massy ‘big’ heroes like Chiranjeevi, Balakrishna and Dr Rajasekhar, pursuing him, but spawned a generation of directors like yesterday’s E.V.V. Sathyanarayana and S.V. Krishna Reddy to today’s Trivikram Srinivas and Anil Ravipudi. None of these directors can deny that they have been influenced by Jandhyala one way or another.

My all-time favourite Jandhyala dialogue is from Srivariki Premalekha. It might lose its punch somewhat in translation but Telugus will know what I’m talking about. The protagonist Naresh’s ill-tempered, wall-butting father, Veerabhadra Rao, suddenly appears at the former’s office.

Naresh: Hello, what, Naanna, did you …er… just come in?

Veerabhadra Rao (breathing through flared nostrils): No, I came yesterday itself and have been since hiding under the staircase.

Finally, it would be unfair if I didn’t use this opportunity to undo an oversight on my part and seek pardon from the master. It pertains to a line in my first novel, Iceboys in Bell-Bottoms: ‘My classmate’s father gave up the shaky world of business and opted for the stability of insanity.’

That isn’t my line at all. It is entirely Jandhyala’s. He has been such an influence on me that I thought I owned his line.

Thanks for the laughter, Haasya Brahma.

Tags

About the Author

Krishna Shastri Devulapalli is a humour writer, columnist, screenwriter and novelist. His novels include Ice Boys in Bell-bottoms, a 1970s bildungsroman, Jump Cut, a seriocomic thriller, and the comic The Sentimental Spy: The Family Bond. His other works include a humorous epistolary play, Dear Anita, and a book of non-fiction, How to Be a Literary Sensation. He has co-edited Madras On My Mind: A City in Stories, and writes regularly for The Hindu, Deccan Chronicle, Scroll, among other journals. He is at present developing a detective series and a young adult show for the web.

.jpg)