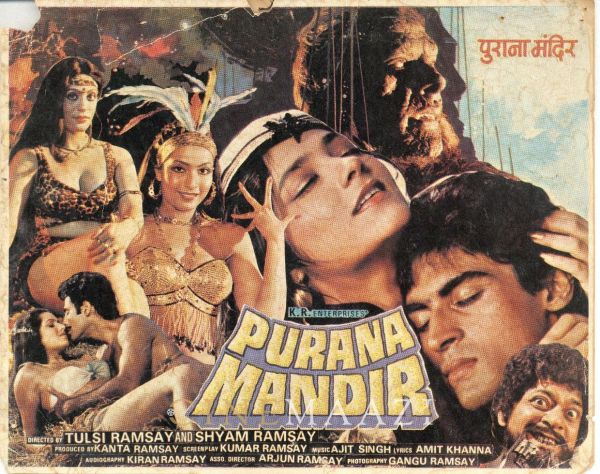

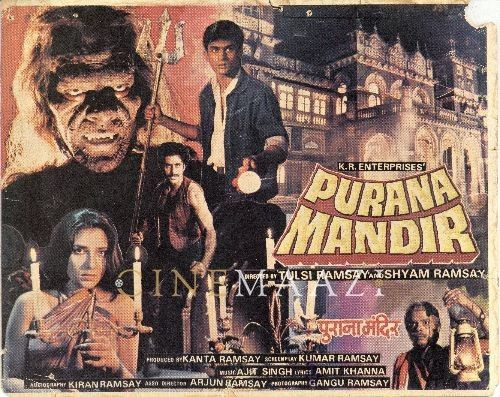

Purana Mandir: How a no-star, A-rated horror film rocked the Hindi film industry in 1984

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

‘In retrospect, the film harmed me.’

‘Everyone just dropped me. All the people I was negotiating with, I was signing films with, were all gone. It was a huge, huge setback.’

‘That finished me, I didn’t have a career left.’

Those, in sequence, are Mohnish Bahl, Aarti Gupta and Anirudh Agarwal. After they acted in Purana Mandir, by many accounts the second-highest-grossing Hindi film of 1984 (there are varying sources with wildly different figures; that’s how it often works in the Hindi film industry). Against all odds. Against all calculations. And, really, against all logic.

Let’s look at 1984 first.

Jaya Prada was the reigning matinee queen, and had fourteen Hindi releases that year (as well as at least five in other languages), at par with the productivity of the busiest male actors of the time. Among them were Tohfa, Maqsad and Sharaabi. Jeetendra was rocking it, as was Sridevi, often in the same film, interchangeably with Jaya Prada. Amitabh Bachchan wasn’t quite out of the picture yet and had, apart from his turn as Vicky Kapoor in Sharaabi, Inquilab (with Sridevi). There was Mithun Chakraborty. It was buzzing. Not just in the mainstream space, but in the parallel film universe too: Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Hazir Ho, Mrinal Sen’s Khandhar, Goutam Ghose’s Paar, Govind Nihalani’s Party, Mahesh Bhatt’s Saaransh, Girish Karnad’s Utsav, and many other highly acclaimed films released the same year, as did – not to forget – My Dear Kuttichathan by Jijo Punnoose, the first 3D film in India.

In that same year, the Brothers Ramsay made Purana Mandir, a film that borrowed heavily from myths and legends, featured gods and godmen, monsters, rebirth (and redeath), passages from popular Bollywood and Hollywood films, added a dash of song-and-sleaze, and laughed all the way to the bank. ‘We made a lot of money,’ Arjun Ramsay, one of the seven brothers, agreed. ‘It’s difficult to say how much, but we still make money from it.’ Many of the men who made the film have passed on, including Arjun, but the moolah still comes home.

What made Purana Mandir click?

The analysis of why a certain cultural artefact worked is surely a matter of guesswork. After the fact of the success or failure of whatever, you find ways to slot things into existing boxes. And that is useful in our desire to make sense of the world, of course. The only other thing we could do is to just accept that a movie – or a book, or a piece of music, or a play – succeeded; perhaps it spoke to the consuming public then. At that particular moment in time, it struck a chord, just appealed to people in a way all the other stimuli out there didn’t.

By that time, the anti-hero magic of Bachchan had started to wear off – he was older and was starting to make public his political ambitions – and ideas were at a premium. On evidence, the commercially successful films were mostly remakes of south Indian potboilers, which helped Jaya Prada and Sridevi waltz in to the scene. And while Chakraborty had earned his space as the twinkle-toed common man’s hero, we were a few years away from the stardom of Anil Kapoor and Madhuri Dixit and Jackie Shroff and, after them, the Khans and Juhi Chawla.

What did Purana Mandir have?

It gave us an ancient human-monster, captured and beheaded and locked up – the head and the rest of the body in separate chests, some distance away from each other – a curse, not explained to satisfaction, and a royal family.

The monster Saamri, barely human with pronounced canine teeth and red eyeballs, goes around raping young women with impunity, eating children and desecrating graves to eat corpses. He might have overstepped his mark when he has a go at Rupali, the princess, and, well, one thing leads to another and there is a beheading. Just before the axe comes down, Saamri issues his curse: all the women who marry into, or out of, the royal family will henceforth die at childbirth. But that was all a long time ago. Cut to now and we are in a city, where Suman (Gupta), the daughter of Thakur Ranvir Ajit Singh (Pradeep Kumar), is in love with Sanjay (Bahl). They reach the old palace to deal with the curse and Saamri (Agarwal), who at some point has put his head and body back together. They want to get married and have children, after all. They co-opt Anand (Puneet Issar), a friend, and his partner (Binny Rai). After a series of unfortunate events, they confront Saamri, and eventually kill him. Sanjay stabs him with a trident and then sets him on fire. And that, really, is what should have been done all those years ago. Indeed, that was the suggestion the court priest had made, which the then king had pooh-poohed. (Thankfully, or there would be no movie then!)

That is, roughly, the outline of the story. Within it are spin-offs and detours, which all add up to a good 40 per cent of the running time of the film.

There’s a full-fledged parody of Sholay in it, with a goofy Gabbar Singh and a goofy Thakur and a rather disturbing Basanti, played by an elderly Lalita Pawar, who is repeatedly raped by Machchhar Singh (Gabbar), much to everyone’s mirth. (Hard not to squirm in our seats in 2020 when these scenes play out.) Now, being a bit of an idiot, this Gabbar keeps getting arrested but Issar manages to rescue him each time, in good-bad-ugly fashion.

Ok, that’s the comedy bit. Not terribly funny, really. That aside, there’s a hint of sex. And that’s a running theme, really, from Bahl training his camera lens on Gupta’s chest after she has come out of the swimming pool to the rather cool track of Rai fantasizing about a roll in the hay (literally) with Issar to Sadhna Khote’s Mangli turning on the heat for Bahl’s benefit … There is romance too, the Bahl-Gupta and Issar-Rai sequences, and there are songs, ‘Woh beete din yaad hai’ the best of them.

‘A non-star cast horror adult film like Purana Mandir has been released in as many as twenty-three theatres’ and ‘at most of the theatres, the picture drew full houses’, wrote V.P. Sathe in Filmfare.

Kartik Nair, in his academic article ‘Fear on Film: The Ramsay Brothers and Bombay’s Horror Cinema’, confirmed that the film ‘finished as the second-biggest money-maker of 1984 […] trailing only B.R. Chopra’s Aaj Ki Awaaz’, which was another surprise hit, starring Raj Babbar and Smita Patil.

Trade analyst Komal Nahta, however, wasn’t so sure: ‘It did well, but No. 2? No, I don’t think so. That seems exaggerated,’ he said. No one disagrees with the number commonly thrown about, though: Rs 2.5 crore in profits (at the time).

‘We sold the rights, and the distributors made the money. But it ran for a long time,’ co-director Shyam Ramsay said. ‘We eventually made money, of course. It was the biggest hit at the time.’ Tulsi Ramsay added, ‘It’s one of the films we still make money from.’

It did make money. Most of it came in from the B, C and D centres, non-metropolitan India. That, really, was where the Ramsays’ core audience lay. Outside the glass-and-steel of the city, where the myths and legends and monsters and witches and zombies assumed a life more real. That said, it wasn’t always by choice that the Ramsays took their business away from the metros.

The battle against seemingly insurmountable odds

Bahl, Nutan’s son, had started out as a supporting hero to Sanjay Dutt in 1983 in a film called Bekarar, and had made two other not-too-exciting films called Meri Adalat and Teri Bahon Mein before he was signed on to play the lead in Purana Mandir. Although, really, Agarwal was the true star of it.

Aspiring to be a leading man, a hero, Bahl remembered how the film got step-motherly treatment at the time of its release, with Bombay theatres being quite under the thumb of the big producers. ‘Yash Chopra had released Mashaal, and if I remember right, the movie was doing well, the first of his films to be doing well after a few unsuccessful films,’ Bahl recalled. ‘We were booked at Metro (theatre) for Purana Mandir, but people from Yash Raj Films spoke to the Metro guys and said they wanted to run Mashaal for longer. That’s how these things used to work. And, compared to us, Yash Raj Films was huge. So the cinema authorities shifted Purana Mandir to a 10 a.m. slot, and gave the four main slots to Mashaal. Thankfully, we got at least that one slot.’

The seven brothers had all been trained in different aspects of film-making by their father, Fatehchand Uttamchand Ramsay, who had produced a couple of not-too-memorable films in Bombay after moving to the city from Karachi following Partition. Of his sons, Tulsi and Shyam became directors, Kumar, the oldest, was the scriptwriter, Gangu was the cinematographer, as was Keshu, while Arjun focussed on editing, and Kiran on sound. They swapped roles around as required, but Tulsi was more than just a technician. He was also the marketing man, the sales executive. As directors, Shyam focussed on the horror and Tulsi on the lighter bits of the films. But Tulsi had another role to play too, one that Nahta’s story explained best.

‘He would come to our [Film Information, the trade magazine] office and demand positive reports for his films. He could be persuasive. Sometimes it was a demand, sometimes it was a request. For Purana Mandir, he hounded us,’ Nahta recalled, adding that it wasn’t within his remit to fudge data.

Whether Tulsi’s ‘tactics’ worked or not, or whether the film just picked up steam on its own, we can’t know, but it undoubtedly caught the imagination of the public.

The Ramsays hit paydirt, but acting in a low-budget, ‘B’ film didn’t help Bahl’s ambitions of becoming a big star, and Gupta, an up-and-coming heroine then, fell off the pedestal.

Success for the film, failure for its actors

He might have felt differently at the time, but Bahl, who did have an acting career, if not as leading man, doesn’t hold a grudge against the Ramsays or the film. ‘In retrospect, the film harmed me. I don’t say it with any malice. Just as a fact. I don’t regret making the film, because it was a great experience, but because of it, I got categorized as a B-grade actor,’ he said. ‘In terms of coverage, I got a lot, because the film became a hit. But in the industry, I got the wrong image. That’s because the industry looked down upon the Ramsay brothers’ films. It’s the limited view of the people in the industry that was the main problem.’

Gupta feels much the same. ‘People said I was a promising newcomer, and some people told me not to do a film with the Ramsays. I didn’t understand it then, but after I did the film, everyone just dropped me,’ she said.

And what about Agarwal? A wonderful man, at peace with himself after all these years. When Agarwal blames Purana Mandir – as well as 3D Saamri and Bandh Darwaza, the other films he made with the Ramsays – for putting him in a box he could never get out of, he does it with the acceptance that, with his appearance, he always risked being pigeonholed. ‘Saamri’ just pushed him on his way.

Six-and-a-half-feet tall, with eyes that seem to bulge out of their sockets and a guttural voice, Agarwal is not exactly hero material. It would be unkind to describe Agarwal thus, only he is brutal about his appearance: ‘I don’t look like a normal person. I have a strange appearance. I know that.’

He never dreamed of becoming a major actor, but Agarwal felt that he stood a chance in negative roles, as a somewhat prominent villain. He did get at least one such major role, as Babu Gujjar in Bandit Queen, but largely, he was either the villain’s monstrous sidekick or the monster.

‘No one thought I could do anything. No one wanted me as a normal man,’ he said during a chat. It can be argued that Purana Mandir gave him a niche. Perhaps not the niche he desired, but a niche he was outstanding in – never before, or since, has there been a greater monster in Hindi cinema.

Thirty-six years later…

… has the film aged well?

Well, the prints of the film haven’t, and that’s due, in large part, to the fact that, to minimize costs, the Ramsays usually shot in 16mm and blew it up for the big screens. It served its purpose at the time, in small, dingy, dark and often dank theatres around the country. The objective was to make people pay money to be scared, and that happened.

Watching the film now, a lot of the sequences jar. The poor – and unnecessarily long – comedy tracks, the amateurish acting, and most of all, the technical deficiencies.

Cost minimizing – it doesn’t excuse bad writing, but it does explain the often-basic camerawork, among other things. ‘You are saying that today, but those days, I used only one camera. Whatever the scene might be, action, night scenes, we set up the lights ourselves (with their small team) and used one camera to create the effects,’ Gangu explained. ‘It was all about being imaginative. I can’t use two-three cameras to create the atmosphere, so what do I do? Carry the camera and track the monster from his back, close-up, or take the camera through an empty corridor to the person who is being attacked. Ideally, these should have been shot with more cameras. But our understanding was that we wouldn’t spend money unnecessarily.’

Keeping the costs low just made the most economic sense. If that meant lack of polish, so be it.

But that’s now, looking back thirty-odd years. It’s what Purana Mandir achieved then that is the wonder, attracting just a fourth of the overall theatre-going audience and trumping some of the best of mainstream Hindi cinema. They had a formula, and this time it worked like a charm. It was possibly the first film by the Ramsays to be written about in leading magazines, because of the kind of reception it got from the audience. Not all the coverage was laudatory, but as Tulsi never failed to remind people who cared to listen, no publicity is bad publicity. The media attention and the word-of-mouth publicity certainly gave Purana Mandir something to step on and launch off. It did. And how!

Tags

About the Author

Shamya Dasgupta works with ESPNcricinfo in Bengaluru, and is the author of Don't Disturb the Dead - the Story of the Ramsay Brothers.

.jpg)