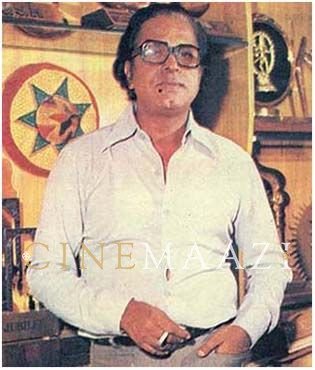

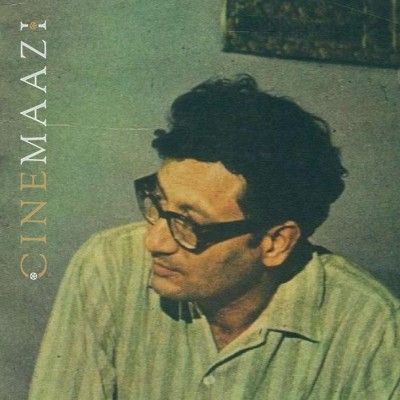

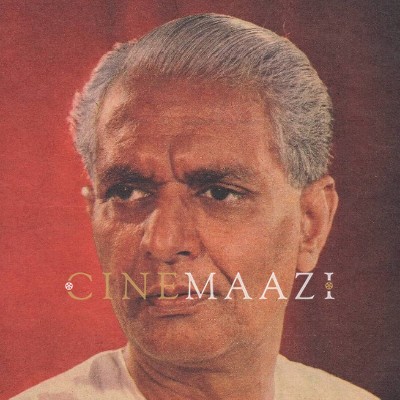

Salil Chowdhury

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 19 November 1922 (Gajipur, West Bengal)

- Died: 5th September 1995 (Calcutta)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Parents: Gyanendra Chowdhury

- Spouse: Jyoti Chowdhury

- Children: Aloka, Tulika, Lipika, Sukanta, Sanjoy, Antara and Sanchari

Salil Chowdhury, lovingly called Salilda, was an influential music composer, poet, and writer in the history of Indian cinema. He worked in Hindi, Bengali, Malayalam, Assamese, Tamil, Telegu, Marathi, Gujarati films in his long career. Known for revolutionising the sound of Indian film songs, he left a rich legacy for generations to come.

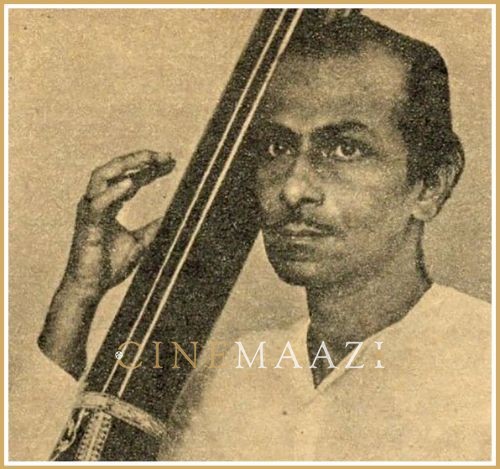

Salil Chowdhury was born on 19 November 1922 in a small village called Gajipur in West Bengal. He spent his early days amidst the tea gardens in Assam where his father, Gyanendra Chowdhury, was a doctor. The vast collection of his father’s western classical records and his engagement in stage plays with the adivasi community of the tea gardens had an impact on his musical compositions later on. Elements of folk music in his compositions can be traced back to his younger days when he grew up listening to folk music of Assam and Bengal. He was also a multi-instrumentalist who played the flute, piano, esraj and the violin.

He graduated from Bangabasi College and spent his formative years during the tumultuous political period of the 40s, Bengal famine and the Indian independence struggle which meant that suffering was a living reality for him like many at that time. Influenced by the socio-political climate of the time, he was exploring and evolving his left-wing political ideologies at the time. This led him to join Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) which was taking form as one of the most important theatre and art movements in India. He was also a member of the Communist Party of India. In an interview, he mentioned about the revolutionary effect Bijan Bhattacharya’s landmark play Nabnanna had on the common people, as the main characters were played by the local peasants. He composed several iconic protest songs during this time, which have become part of the lexicon of people’s movements over the years. His songs used to be performed by touring musical groups in the Bengal countryside. Hei shamalo dhaan ho, O moder deshobashi re, Kono ek gayer bodhu, Dheu uthche kara tutche are some of his songs which became emblematic of the political landscape of Bengal in the 40’s. The poetic lyrics of his songs were accompanied by tonal and textual novelty with influences ranging from folk tunes to Mozart, Hanns Eisler and Latin American music. From 1944 to 1951, Salilda wrote and composed several songs, some of which were never recorded. He called them songs of consciousness or chetonar gaan. These songs have become an integral part of Bengali culture and heritage and are widely popular till date.

Salilda’sexperimentation gave the modern Bengali song a new sound, prior to which Bengali music had a simpler arrangement. In the writing process, he diverted from the norm by writing complex phrases that spanned over couple of lines as lyrics. The tonal expressions in his compositions varied based on the rhythm arrangements, melodies and the notes.

In 1959, his collaboration with Lata Mangeshkar in the song Na jeo na is celebrated till date. Jodi baron karo tabey jaabo na (1968), O more moyna go (1975) and Jhim chiki chak (1980) are a couple of the wonderful tunes we got from their collaboration over the years.

Besides being a musically gifted person, he was also an accomplished writer and poet. His lyrics evoked the despair and anguish at the injustice faced by people. The iconic poet Sukanto Bhattacharya was friends with Salilda who gave tunes to a couple of his poems like Runner and Abak prithibi. His own poetry was often scribbled behind a closeby envelope or a loose paper, written in easy but stirring words. Only a few of his poems have survived and were compiled into a collection called The Poems of Salil Chowdhury after his death, which is out of circulation now.

Some of his celebrated short stories are Dressing Table and Sunya Puron. Chaal Chore was the first play he wrote. Interestingly, it was his writing that led him to the film world. His Bengali film script Rickshawala impressed Bimal Roy who gave him the opportunity to write the Hindi version of the script – Do Bigha Zamin (1953). He also composed the music for the film. Do Bigha Zamin’s success in international circuit established him in Bombay. Two years later, the Bengali film Rickshawala was made and was successful with the audience.

Evergreen Hindi film songs like Zindagi khwab hai from Jagte Raho (1956), Dil tadap tadap ke keh rahe hain, Suhanan safar aur yeh mausam haseen from Madhumati (1958), O sajna, barkha bahar ayi from Parakh (1960), Ae mere pyare watan from Kabuliwala (1961), Koi hota jisko apna from Mere Apne (1971), Zindagi kaisi yeh paheli hai from Anand (1971), Na jaane kyon from Chhoti Si Baat (1976) were all composed by Salil Chowdhury. He composed songs for Hindi films like Biraj Bahu (1954), Amaanat (1955), Apradhi Kaun (1957), Madhumati, Usne Kaha Tha (1960), Kabuliwala (1961), Jhoola (1962), Ittefaaq (1969), Sara Akash (1969), Anand, Rajnigandha (1974), Chhoti Si Baat, Minoo (1977), Kanoon Kya Karega (1984), Kamla Ki Maut (1989) and Mera Damaad (1995).

He also enjoyed a successful career in Bengali cinema after making his debut as a composer in the 1949 Satyen Bose film Paribartan. Some of his most beloved Bengali film songs are Shimul shimul shimulti (Barjatri, 1951), Jhir jhir borosay (Pasher Bari, 1952), Ei duniyay bhai shobi hoy (Ek Din Raatre, 1956), Deko na more deko na (Lal Pathore, 1964), Haay haay pran jay (Marjina Abdallah, 1972), Baje go beena (Marjina Abdallah, 1972), Bujhbe na keu bujhe na (Kabita, 1977) and O amar sojoni go (Swarna Trishna, 1989).

Ramu Kariat, the daring Malayalam filmmaker approached him and the two collaborated to make one of the most memorable Malayalam film songs from the 60s- Maanasamaine varoo for the film Chemmeen (1965). It was an unusual choice to have a non-Malayalam composer in the first place, but the duo made a bolder move and roped in Manna Dey to sing the only Malayalam song in his career. The film won the Presidents’s Award in 1965, which established him in the industry. Salil Chowdhurywent on to have a strong influence on the new sound of Malayalam film songs. He went on to compose for 27 other Malayalam films such as Abhayam (1970), Nellu (1974), Aparadhi (1976), Madanolsavam (1977), and Anthiveylile Ponnu (1982).

An element that distinguished his compositions from others was the novel use of techniques like harmony and choir in the film songs. Additionally, he used orchestration with various chord progressions to aid the melody. Apart from composing songs, he was also involved in scoring the soundtrack of the films he worked in. According to him, the soundtrack gave life to the film, and rightfully so. Often, he would ask the filmmaker to describe him the scene and composed the music to fit the situation.

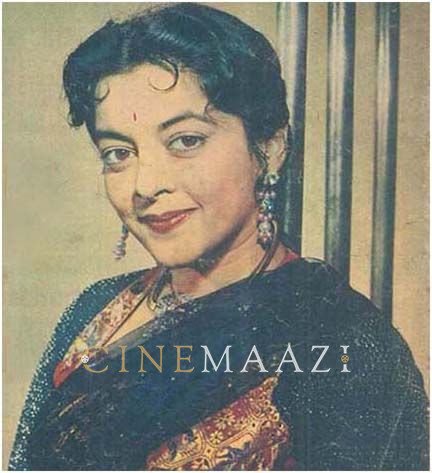

The 1966 film Pinjre Ke Panchhi starring Balraj Sahni, Meena Kumari and Mehmood was his directorial venture. He wrote the script and composed the music additional, assisted by Gulzar’s lyrics, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s editing and cinematography by Kamal Bose.

On the personal front, he was married to Jyoti Chowdhury in 1953. They had three daughters together - Aloka, Tulika and Lipika. A while later in his life, he got together with Sabita Chowdhury and had Sukanta, Sanjoy, Antara and Sanchari. Sanjoy and Antara Chowdhury have carried on their father’s legacy and are established musicians too.

With the change in the 1970s industry, Salil Chowdhury moved back to Calcutta where he established the Centre for Music Research and opened the recording studio called Sound on Sound. He remained true to himself and spoke about the disheartening commercialism of mainstream media.

On 5th September 1995, he passed away in Calcutta.

.jpg)