What a Wonderful World: Mrinal Sen’s Amaar Bhuvan

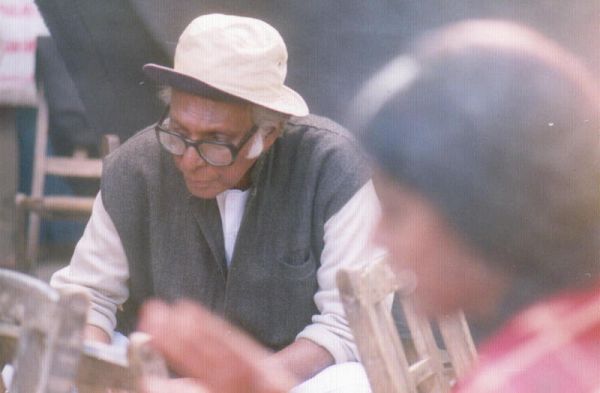

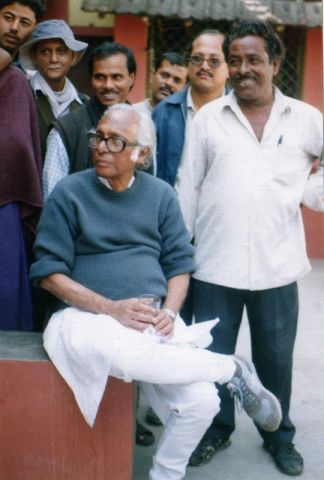

Eschewing the pitiless exploration of the human condition in all its depravity and despair that marked his oeuvre, Mrinal Sen’s swan-song is unlike any other film by the film-maker. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at what is an ode to simplicity and human dignity and a fitting finale to a great career.

A close-up of an impoverished girl weighed down with what looks like a bundle of clothes – it is a child – flung across her shoulders. Flashes of light illuminate the dark screen. The soundtrack is awash with a cacophony of gunfire, bombs whistling … Prithivi bhangche, pudchhe, chino-bhinno hochhe … tobuo manush bechebarte thake … mamowtwe, bhalobashaye, sahomarmitaye … THE WORLD BREAKS UP, BURNS, DISINTEGRATES; STILL MEN LIVE THANKS TO LOVE, COMPASSION EMPATHY – as these words fill up the screen it seems like the film-maker is back to what he does best: throw up in focus the dark underbelly of the world we live in. But the mood changes almost immediately as Srikanta Acharya’s mellifluous vocals fill up the soundtrack. The next title slide reads: Rabindranath Thakurer gaane samriddha – enriched by the song of Tagore… The titles fade out to an idyllic rural panorama. What follows over the next 100 minutes is unlike any other Mrinal Sen film.

It had been almost a decade since Mrinal Sen had made his previous film, Antareen (1993), based on a story by Sadat Hasan Manto. He had in the interim toyed with the idea of adapting Bimal Kar’s Bhubaneshwari, writing a treatment for a film. Looking for an actor to play the old lead in it, he even approached Dilip Kumar, but the project went nowhere. It was at this stage that in the wake of the Kargil war, he happened to watch a news correspondent asking a roadside vendor in Islamabad about what the war had meant to him. The man’s one-word answer – ‘nuksan’ (‘loss’) – provided the film-maker with the seed of the idea for Aamar Bhuvan. As Mrinal Sen told his biographer: ‘See the dimensions one single word can offer. I may even make a film based on this word!’

Their lives intersect as one day Nur turns up at Meher’s place and asks for a glass of water. Even as Sakhina offers him a tumbler, there’s a hint of their fingers touching, and as the glass falls to the ground, both bend simultaneously to pick it up. All of a sudden, the moment and the relationship are rife with possibilities. Meanwhile, Meher toils at odd-jobs while trying to escape the clutches of the moneylender.

Given the grinding poverty that Meher and Sakhina endure, the looming presence of the moneylender and Nur’s obvious fondness for Sakhina, one would expect the film-maker to come up with his trademark take on oppression and exploitation. But as I have mentioned, this is unlike any other Mrinal Sen film, and so every time the narrative comes up with something potentially ominous, the director adroitly changes tack. You are sure of Nur having ulterior motives when he offers Meher work at his pond site. You half-fear for Sakhina when the moneylender times his visit to Meher’s home when he knows Sakhina will be alone. Yet, even this most hated of figures in Indian films comes across as merely effete and almost comical, wilting under Sakhina’s angry gaze, dropping his flashlight in fear and confusion. Even the film’s most dramatic strand – pertaining to a nose-ring that Nur had given Sakhina after their marriage and which Sakhina now asks Nur to pawn to repay the moneylender, which he does to none other than Nur – only highlights the simplicity and inherent goodness of the dramatis personae.

Another novelty that marks the film is in its use of music to convey the mood and nuances – beginning with the title track and then in the little episode involving Sakhina fondling the nose-ring in her box of earthly possessions as a couple of lines from a folk song, ‘Bhanga chaal bhenge gechhe’, complement the ruminative nature of the scene. Also marking a drastic departure from everything he had done before, Mrinal Sen incorporates Rabindrasangeet into the narrative. Unlike Satyajit Ray or Ritwik Ghatak, or for that matter any other Bengali film-maker, Mrinal Sen had never used a Tagore song in his films, barring one in Pratinidhi (1964), or for that matter ever filmed a Tagore story. The only other reference that he made to Tagore is in the title of one of his bleakest films, Baishey Shravan (1960). This reluctance to go back to Tagore probably stems from his experience of attending Tagore’s cremation in August 1941. All other cremations for the day had been put on hold. As the huge procession with Tagore’s body surged its way into the cremation ground, Sen, to his horror, saw another man waiting with the body of his little child wrapped in a towel lose his hold on the child’s body which fell to the ground and was crushed under the avalanche of mourners. As such, when he made a film delineating the end of a relationship between a couple, he fixed their anniversary on the twenty-second (or Baishey) of Shravan, the death anniversary of Tagore.

Lyrical and idyllic are not terms you associate with Mrinal Sen. But these are the words that come to mind watching Amaar Bhuvan. Time and again one is reminded of the simplicity of Iranian films like Where Is My Friend’s Home. Time and again one has a smile at the interactions. How many Mrinal Sen films can you say that about? Consider, for example, Meher at the electronics shop, exploring the possibility of buying Sakhina a radio, transfixed by the antics of Charlie Chaplin on the TV set. The film-maker, who considered Chaplin a huge influence, cheekily incorporates a cat-and-mouse game between Meher and the moneylender mimicking Chaplin’s escapades with the policeman playing out on the TV. Or for that matter Sakhina’s reluctance to go to Nur’s dawat. As Meher and his daughter try to reason with what seems her hard-headed intransigence, she offers her reason – she has neither a proper sari nor a hawai chappal – before bursting out in sassy laughter. Nandita Das, who is brilliant right through, is a standout in this particular sequence as also in many involving her loving exchanges with Meher. Or the scene where Nur comes to invite Meher’s family to the dawat, espies upon Meher’s son, Shaju, playing with his motorcycle and offers him not only a ride on it but also takes him home for the night. Again, as Sakhina expresses her concerns about Nur and his wife doing some ‘tuk-tak’ (black magic) on Shaju, the gathering tension is dissipated by her impish laughter – the idea is too preposterous in this world that the film-maker has created. Or the way Tagore’s ‘Mamo chitte niti nritye’ is used in the sequence in which Meher manages to get Sakhina a radio, from the money he receives by mortgaging Sakhina’s nose-ring!

Photography: Avik Mukhopadhyay

Story: Afsar Ahmed

Editing: Mrinmay Chakraborty

Art: Gautam Basu

Music: Debojyoti Misra

Winner of the Best Director Award for Mrinal Sen and the Best Actress Award for Nandita Das at the Cairo International Film Festival

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)