Tapan Sinha: His Encounters with Hindi Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

The films of Tapan Sinha have not received the attention that his more celebrated contemporaries Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak have. In this essay, Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at his influence on Hindi films…

It is one of the first films I ever watched. Almost forty-two years later, there are still some vignettes that have stayed on in memory: the sight of a majestic white elephant (it didn’t matter at the time that Dad told me there were none of the variety, and I was still years away from understanding the meaning associated with the phrase in economics) against the colourful sky, a pot of gold mohurs being overturned by a greedy couple before they are attacked by snakes protecting it, and a young boy rousing an army of jungle animals to rescue their king, the elephant Airavat. At the age of nine, the title credits held no attraction at all and I am not sure I was even aware that a film had something called a director. And it is only in hindsight I realized that the film was in many ways an exception for the times: a true-blue children’s film in Hindi, Safed Haathi (1978). (The other films I watched around the same time in the sleepy back-of-beyond that Bokajan used to be were Sholay and Yaadon Ki Baaraat!) But then, as I would grow up to recognize, the director was exceptional in many ways: Tapan Sinha.

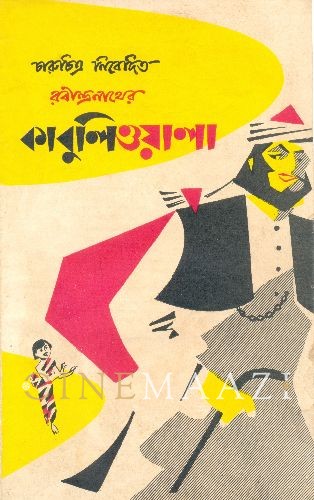

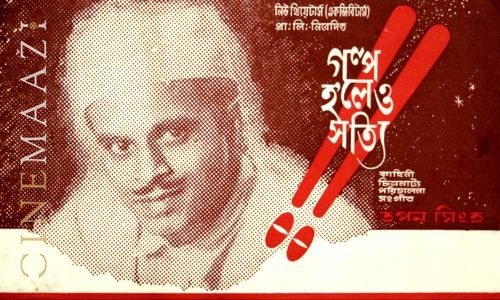

Tapan Sinha occupies a unique place in the annals of Bengali and Indian cinema. Active during a period when the troika of Satyajit Ray-Mrinal Sen-Ritwik Ghatak was setting international forums abuzz with their films, Tapan Sinha carved a distinctive niche for himself with films that seamlessly matched the arthouse with commercial success. As Taran Deol says, ‘The kind of films we see today, where the line between parallel and mainstream cinema is blurring, were being made by Sinha long ago.’ And he did this consistently over an oeuvre consisting close to forty feature films traversing an entire gamut of genres – literary adaptations (primarily Tagore, as in Kabuliwala, Kshudita Pashan, but also Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, Samaresh Basu and Subodh Ghosh), swashbuckling adventures (Jhinder Bandi), rip-roaring comedies and satires (Golpo Holeo Satti, Ek Je Chhilo Desh and Banchharamer Bagan), contemporary sociopolitical dramas (Apanjan, Atanka, Adalat O Ekti Meye), period pieces like Sagina and films for children (Sobuj Dwiper Raja, Aaj Ka Robinhood).

Adaptations by Other Filmmakers

One of the most well-known adaptations of Tapan Sinha’s films is of course Hemen Gupta’s version of Kabuliwala (1961), produced by Bimal Roy, whom Tapan Sinha had observed closely during his stint as a technician at New Theatres. Though Chhabi Biswas was an impossible task to follow and Tinku (as Minu) is probably one of the finest child-acts in Indian cinema (the Hindi film suffers from this more than anything else), Balraj Sahni comes up with one of his best performances. And of course, there’s Aye meray pyare watan and Ganga aaye kahan se, still capable of moving the listener.

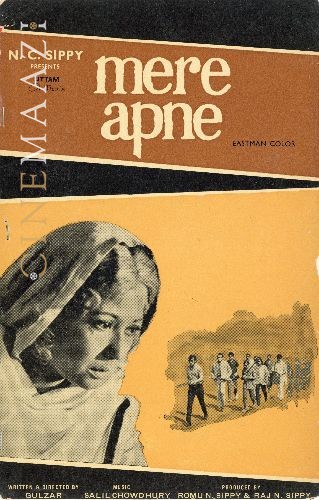

The next major adaptations of Tapan Sinha’s films came in 1971 and ’72 respectively with Gulzar’s Mere Apne and Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bawarchi. The former was a remake of Sinha’s 1968 film Apanjan, a take on the lumpenization of youth and the way political leaders exploit and misguide unemployed young people. Against the backdrop of the gang-wars between two groups is juxtaposed the story of the aged widow Anadamayee (Chhaya Devi) who has left her home in the village and come to the city and who becomes a surrogate mother to the members of the two groups. Gulzar’s debut directorial feature cast Meena Kumari in one of her last roles, and provided a boost to the careers of its relatively new stars Vinod Khanna and Shatrughan Sinha. Gulzar also directed Lekin … (1991), which was touted as a take on Kshudito Pashan, though personally I feel that’s stretching the comparison a bit. Despite its classy music which went a long way in stemming the tide of crass music that marked the 1980s, Lekin… lacks the dreamlike, hallucinatory quality of Kshudito Pashan. Sinha’s Jatugriha, based on a story by Subodh Ghosh, was also the inspiration for Gulzar’s Ijaazat, an adaptation that Gulzar gave his own impeccable spin to.

.jpg)

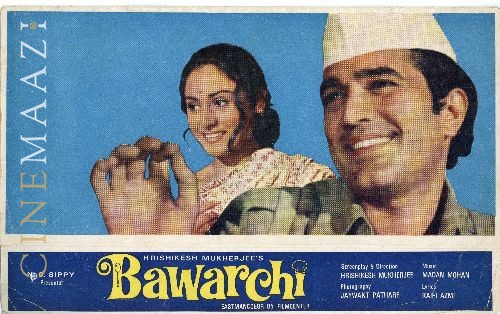

Hrishikesh Mukherjee adapted a couple of Tapan Sinha films – Arjun Pandit (1976, which fetched Sanjeev Kumar the Filmfare Award for Best Actor) based on Aarohi (1964) and Bawarchi on Golpo Holeo Satti (1966). Of these, Bawarchi is the more celebrated film. In a film that had a glittering galaxy of some of the finest character actors of Bengali cinema – including Chhaya Devi, Bharati Devi and Bhanu Bandopadhyay – Tapan Sinha made a coup of sorts casting Rabi Ghosh, so far seen primarily as a comic sidekick, as the protagonist Dhananjoy who arrives as a cook and manservant to set a dysfunctional family in order. And what a delight it is to watch two of Bengal’s greatest character and comic actors, Rabi Ghosh (who even gets to sing Ka tabo kanto) and Bhanu Bandopadhyay, feeding off each other in the two sequences they have together. Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s much-loved film is an almost scene-for-scene remake, with Rajesh Khanna admirable as the cook. Of course, the casting of Rajesh Khanna comes at the cost of the earthiness that Rabi Ghosh brought to the original, though in ways it adds to the fable-like quality of the story. Hrishikesh Mukherjee steers clear of the social/political commentary of the original, so that Bawarchi is more of a comedy than Golpo Holeo Sotti.

There were a couple of other remakes, including Atithi, another film based on a Tagore story which provided the template for Hiren Nag’s Geet Gaata Chal (1975) marking the transition of Sachin and Sarika from children’s roles to grown-up ones and whose brilliant music continues to be popular even today. There was also Alo Sarkar’s disastrous remake of Jhinder Bandi (1961) called Bandie (1978), which cast Uttam Kumar in a double role, though in a different setting. The film fared no better than Alo Sarkar’s Hindi production, Chhoti Si Mulaqat (a remake of the Uttam Kumar classic Agni Pariksha), the star’s debut in Hindi films, which all but finished any chances Uttam Kumar had of making it big in Bombay cinema.

Tapan Sinha’s Own Remakes

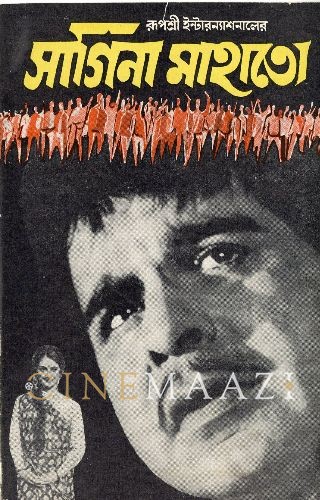

Tapan himself remade two of his films. But even before he got down to doing that, he blazed a trail of sorts, casting top Hindi film stars in his Bengali films: Ashok Kumar and Vyjayanthimala in Haatey Bazarey (1967) and Dilip Kumar and Saira Banu in Sagina Mahato (1970). Working with these leading stars allowed Tapan Sinha to expand the reach of Bengali cinema, a step that was taken forward by Rituparno Ghosh in the 1990s.

The Original Directorial Ventures

It was with his original directorial ventures – Aadmi Aur Aurat (1982) and Ek Doctor Ki Maut (1990), in particular – that the director left his mark on Hindi films. Aadmi Aur Aurat was made for Doordarshan, which gave the filmmaker the kind of freedom one rarely got, allowing him to film it in the local dialect, Angika. As he himself admitted, it enabled him to break away from the kind of films he had done and make one the way he wanted to, with an economy of expression that commercial considerations seldom allowed.

The rest of the film documents the couple’s journey through the rough and unforgiving terrain – making their way over boulders and through forests and across an overflowing river, even as a close bond builds between them. The woman tells the man of her first miscarriage and how her husband has had to borrow Rs 40 from the local lala in exchange for seven days of labour to give her for her journey to the hospital this time round. As the woman is close to collapsing time and again out of sheer exhaustion, the man rises to the challenge, keeping her engaged in conversation – about his many hunting experiences, his hilarious stint as part of a film unit, enacting a bit part as a rabblerouser and then being disappointed at the film with no songs or dances (Tapan Sinha taking a good-natured dig at the kind of serious films that marked the New Wave?), carrying her in his arms part of the way, crafting a stretcher for her and pulling her along, before finally wading through the river, as the man goads her all along with a primeval call to hope: ‘We will live like the sun … we will live … we are immortal … the child will herald a new dawn.’

It is for both actors an intensely ‘physical’ portrayal and they come off superbly while making the underlying statement on human empathy. The film’s closing moments – when the man learns of the identity of the woman’s husband, one Anwar Hossain (the woman remains nameless) – gives the film an unforgettable universal dimension. Amol Palekar’s reaction to this revelation should count among his finest moments on screen. In an interaction about Tapan Sinha, he mentioned that for the last scene of the film he was too emotionally drained and exhausted and simply couldn’t conjure the necessary tears. A number of takes followed and the director okayed the last one though the actor wasn’t satisfied. The next day, as they were preparing for another scene, Tapan Sinha announced that they would do a retake of the last scene. Though Amol Palekar was taken aback, the director insisted. Unprepared for the shot though he was, the actor managed to cry even without glycerine and delivered the perfect shot. Tears in his eyes, the director could only say: ‘There was no way I could let my hero remain unhappy.’

No wonder one of the film’s champions was Satyajit Ray who wrote to the filmmaker calling it not only Tapan Sinha’s best film but also one of the best films ever made in India. It bagged the award for the Best Feature Film on National Integration at the 32nd National Film Awards. In a year in which films like Ghare Baire and Paar (the film’s parallels with Gautam Ghose’s masterpiece call for another essay) created a splash, Aadmi Aur Aurat, much like the director’s many other films, made a quiet statement.

By all consensus, Ek Doctor Ki Maut remains Tapan Sinha’s best Hindi feature film. Based on Ramapada Chaudhuri’s Abhimanyu, the film is inspired by the real-life story of Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay who pioneered research in the field of in-vitro fertilization in India. However, bureaucratic wrangling and ridicule in the scientific community, arising out of professional jealousy, prevented him from sharing his research, and from being acknowledged as the first person to successfully complete the IVF process, a recognition that went to the UK’s Louise Brown. His life’s work coming to naught, Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay took his own life.

After ten long years of research, he manages to create a vaccine that could prevent leprosy, and this is when the nightmare begins. The director creates a despairing and often-frightening scenario of bureaucratic red-tapism and professional rivalry. His only allies are his wife, a senior colleague Dr Kundu (Anil Chatterjee) and a news reporter Amulya (Irrfan Khan in an early role). What also goes against him is his perceived ‘arrogance’ as he refuses to kowtow to people he believes are not qualified enough to engage with him. However, the point the director is trying to make here is that this is a man not given to false humility – his confidence in his ability and his frustration with the tyranny of mediocrity that he has to deal with is what gives him the veneer of arrogance.

Dr Ray is hounded out of Kolkata and transferred to a remote village which brings a halt to the preparations of his papers to defend his research. In what is probably the film’s most moving sequence, walking down the seashore with Seema, Dr Ray likens the waves to questions of science – small and big – which he seeks to answer, the stars in the sky challenging him to go beyond the pettiness of everyday life.

Eventually the delay in his preparations leads another scientist in the US to lay claim on the vaccine, marking the death of another creative innovator in India. However, unlike the fate that befell Dr Mukhopadhyay, Tapan Sinha ends the film on a note of hope. In keeping with what Dr Ray says earlier in the film – there is no full stop in science – he gets an opportunity in the UK and migrates. In a telling scene involving an ‘expert committee’ set up to judge the credibility of his findings, Dr Ray announces his ‘surrender’ in the face of intransigent politics that will always stymie all attempts at excellence. It is a searing indictment of academics in India, riven by politics and bureaucracy, and which can easily be applied to all creative endeavours in this country.

Interestingly, Tapan Sinha had started work on a Bengali film based on Abhimanyu, with Soumitra Chatterjee and Madhabi Mukherjee in the lead. The film remained incomplete as the producer backed out. However, his faith in the subject was vindicated as Ek Doctor Ki Maut won three National Film Awards including the National Film Award for Second Best Feature Film (‘for making a very relevant social comment, presented in a tremendously communicative yet emotional manner’), National Film Award for Best Direction for Tapan Sinha and the Special Jury Award for Pankaj Kapur (having effectively projected the in-built trauma of an aspiring, thinking, creative mind, in the context of a demoralizing, fossilized establishment that does not provide scope for fruition of a path-breaking spirit’).

Tapan Sinha made a couple of more Hindi films – Safed Haathi (1978) and Aaj Ka Robinhood (1987) – his endeavour to address the fraternity of children. Like his work in many other genres, this exceptional filmmaker brought his unique sensibilities to his work for children that deserve a separate study of their own.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)