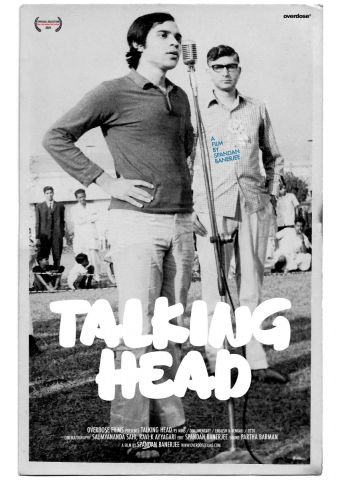

Spandan Banerjee’s documentary on Dhritiman Chaterji, Talking Head, is as much an ode to a lost era as it is an enigmatic look at the life and times of an enigmatic star and actor. Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri spoke to the director…

What do you regard as the most outstanding and significant event of the last decade?

SIDDHARTHA

The war in Vietnam, sir.

INTERVIEWER

More significant than the landing on the moon?

SIDDHARTHA

I think so, sir.

INTERVIEWER

Could you tell us why you think so?

SIDDHARTHA

Because the moon landing … you see, we weren’t really unprepared for the moon landing … we knew it had to come some time, we knew about the space flights, the advance in space technology … so we knew it had to happen. I am not saying it was not a remarkable achievement. It wasn’t unpredictable, the fact that they did land on the moon…

INTERVIEWER

You think the war in Vietnam was unpredictable?

SIDDHARTHA

Not the war itself but what it has revealed about the Vietnamese people, about their extraordinary power of resistance … ordinary people, peasants … and no one knew they had it in them … this isn’t a matter of technology, it’s just plain human courage, and it takes your breath away.

INTERVIEWER

Are you a communist?

Time has not dimmed its power one bit in fifty years. Mention Dhritiman Chaterji and any film aficionado worth his salt will hark back to this iconic sequence and to the other explosive one involving candidates stewing in the heat waiting for an interview, which leads to the most explicitly angry sequence in any Satyajit Ray film. I have always believed even if Chaterji had done no other film in his life, he would have been an important part of Indian film history solely on the strength of Pratidwandi. The film and its protagonist not only captured the zeitgeist of an era like few films do, it also made a star of Chaterji, underlined by Ray no less when he said: ‘I do not know what definition of a star these filmmakers have been using, but mine goes something like this. A star is a person on the screen who continues to be expressive and interesting even after he or she has stopped doing anything. This definition does not exclude the rare and lucky breed that gets lakhs of rupees per film; and it includes everyone who keeps his calm before the camera, projects a personality and evokes empathy. This is a rare breed too but one has met it in our films. Dhritiman Chaterji of Pratidwandi is such a star.’

It is therefore in the fitness of things that even as Pratidwandi celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 2020 we have Spandan Banerjee’s Talking Head. And it is not surprising that the film occupies a large part of Banerjee’s take on the actor. In the light of the actor completing fifty years in cinema, how does Talking Head measure up?

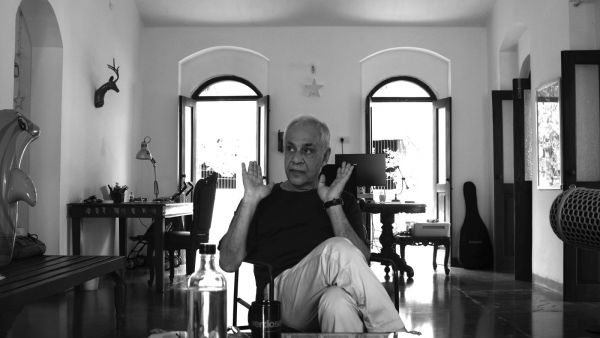

If one is expecting a deep-dive into the actor’s life, work and times, as I was, one is likely to be disappointed. Talking Head is more in the nature of vignettes of a life and time than a full-fledged chronological account of the subject. Chaterji has spoken at length on Pratidwandi, on Ray and Mrinal Sen at various other forums and there’s little in Talking Head on those aspects that anyone who has followed the actor is not already aware of. It would have been worth hearing him talk about his less heralded performances in films like Sarisreep and Sunya Theke Shuru (he was as brilliant in these as he was in the more celebrated films with Ray and Sen, showing a willingness to push the envelope) or indeed about his foray into Hindi and other-language cinema in the last fifteen years.

It is telling that in the twenty-odd years after Pratidwandi, till the early 1990s, Chaterji starred in only nine Bengali films. In the last fifteen years, since 2005, he has acted in approximately thirty-six films (fifteen Bengali, thirteen Hindi, five English, one Sinhala and two Malayalam). What accounts for this prolific output this late in his career? How does he reconcile himself – given that he has often considered himself somewhat of a misfit in mainstream Bengali and Hindi films of his era – to being a part of films like Agent Vinod and Guru? Talking Head does not provide an answer.

Instead what it does offer are snapshots of Calcutta in the 1970s – before it became Kolkata and lost its unique character – the turbulent decade in which Chaterji made his mark as an actor and began his journey in advertising. There are a few delectable nuggets from the interviewees – his wife Ammu, son Pablo and friend Ayesha Sayani – that give an insight into a bohemian era, best captured by Pablo’s memory of growing up with the ‘smell of marijuana’ around him or that his first birthday was celebrated in a pub! Ammu too has some interesting observations on Chaterji’s very independent-minded mother – who knew how to play the piano and ride horses and was the first woman commerce graduate in Calcutta University – and indeed his grandmother who could fly a two-seater plane and who drove all the way through riot-affected Calcutta during the Partition to get ilish maach from Howrah! However, there’s little on the actor or on how these influences shaped him.

In fact, Spandan has inputs from only these three people and Tinnu Anand (who shares an interesting anecdote about his first reaction to meeting Chaterji and learning he was being considered for the lead in Pratidwandi till the look test came in). Even Tinnu’s reminiscences cover the filmmaking of the era more than insights into the actor’s life and craft. And though there’s a substantial bit with Sandip Ray at the time of dubbing Professor Shonku O El Dorado, there are no bites from the director.

As far as Dhritiman Chaterji’s own take is considered, he makes a typically iconoclastic albeit elliptical statement on stardom through two demigods of cinema and their wigs! ‘I was, once upon a time, tempted to dye my hair, but just love the silver now,’ Chaterji says, before going on to recount a fascinating explanation that Shyam Benegal offered about wigs and makeup in classical dance forms. And there’s one wonderful bit about the insecurities that plague megastars when Chaterji talks about Uttam Kumar on the sets of Jadu Bansha (1974), where Chaterji’s monologue was eventually shot with only the mahanayak in frame instead of being an over-the-shoulder shot as initially planned (while Chaterji delivering the monologue is seen through a mirror in the frame). Chaterji is equally blunt about filmmakers who took advantage of the FFC and NFDC’s scheme to finance ‘art’ films of the era and who – unlike Ray who was perpetually mindful of making good the producer’s investment – had no intention of ‘returning the money’. But none of these are followed through.

That apart there are a couple of interesting memories he shares, one about a virtuoso cameraman friend, Mahendra Kumar (a delightful little aside on Ritwik Ghatak informs this) and the other about a pioneering lab owner and engineer – both shot outside the actual location where they had their abodes. But like the hilarious anecdote on Chaterji being offered the lead in Piya Ka Ghar and what eventually drove him to reject it, these are abruptly cut to the actual shooting of the documentary replete with interruptions – a phone call, a plumber’s visit, the actor being applied make-up.

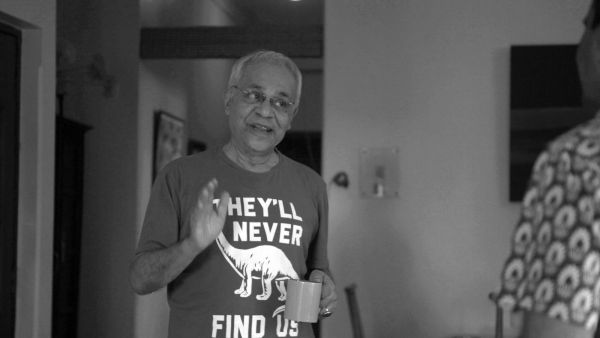

Coming to which … these interruptions make for an engaging style and structure, a certain disarming randomness in keeping with the actor’s approach to his film career. It also provides an element of intimacy to the film – almost like a home video shot on a leisurely afternoon. In the process the film becomes as much a ‘making of’. However, what I found irksome beyond a point were the repeated cuts to films clips, including those of Kaalia and Main Azad Hoon (Tinnu Anand directed these films). And what to me seem like random insertions of songs – the film begins with Begum Akhtar’s ‘Jochhona korechhe ari’ playing on the turntable and then goes on to include ‘Listen to the falling rain’ and ‘Jambalaya’ (with which the film comes to an abrupt end), among others. Despite what these interruptions might do for the narrative style, I for one – as someone looking for more about the actor and insights into his life and art – kept getting distracted by what I perceived as rather arbitrary insertions.

In the end, even after 94 minutes, the film’s run-time, its subject remains, as he is described early in the film, an ‘elusive star’. I wonder whether that is the film’s achievement or its failing.

INTERVIEW

1. What is it that attracts you to the subject to want you to make a film – what was your vision re the film?

Sometimes a film is a form of memoir. In the summer of 2019, I started telling a story about an actor unattached to the frills of stardom. It was to be a story about parallel cinema and the untold around it. Life as we knew it changed around March 2020. This film is a biography of a person and an era. It is a memoir of a man, a time and a city that once was. It is an archive of stories that may classify as film history.

My purpose as a documentarian is also to capture and create an archive of stories and people. I hope that Talking Head will become an archive of the kind of cinema and filmmaking we saw in the India of the 1970s, particularly in Calcutta. This is also the second of my film series that will archive stories and memories. My earlier film You Don’t Belong (2011) was about a song that tells a story of a specific time in the musical history of Bengal.

2. How much time did it take to complete the film? What were the challenges?

I met Dhritiman for the first time when both of us were serving as jury in one of the state film festivals in 2018. We met only a couple of times after that till I decided to make Talking Head in 2019. The world changed in 2020 with the pandemic, which redefined life for all of us. The challenge was to continue and finish the film while scrambling for hope. Things went crashing down way too fast and words like ‘struggle’ and ‘challenge’ took a totally new meaning.

3. How difficult was it to get Dhritiman-da to open up?

When I film my subjects, I usually get to know them in the process of my storytelling. This curiosity drives my stories and me as a director. And yes, I’ve been fortunate enough to meet some fantastic people in my journey as a filmmaker. For Talking Head also I never faced any difficulties from my character, it was exactly the way it is shown in the film; relaxed and informal.

4. You have focused on his Bengali films that are well known – Pratidwandi, Padatik, Akaler Sandhane – however, other well-known and offbeat films like Sarisreep, Sunya Theke Shuru etc., ...haven’t found mention. Don’t you think a documentary on him needed to cover a bit more...

The film tries to capture Calcutta, the cinema of the 1970s and ’80s in India through an eminent actor. It tries to unravel the mystery and mythology around an actor who worked with the masters of Indian cinema. To me, it is one of the many films that can be made on this subject. The film tells you stories which might have been already known or talked about before across different forum, but that doesn’t take anything away from the charm and intimacy of this little film. I’m sure more work can always be done on his work and later films. A single piece of work, or a film can only do so much. I’m never a believer of loading too many things for the sake of information or coverage.

5. There’s very little, almost nothing on his non-Bengali career, which has been quite substantial in the last 15 years. Was that a conscious decision?

Personally speaking, Dhritiman to me is not a ‘Bengali’ actor. He inhabits a space which I think goes beyond the language barrier. And Talking Head does show his other work, including Hindi, English, Sinhala and Malayalam.

6. Apart from Ammu-di, his son Pablo, his friend Ms Ayesha Sayani and Tinnu Anand, there are no other voices and opinions … don’t you think getting other filmmakers and actors he has worked with would have added to a more rounded picture of the actor and man?

I think the most important and omnipresent voice in Talking Head is mine, and how I see the actor and his work. In a way it is also subverting the idea that every person associated with a documentary subject (particularly famous or a known figure) has to be interviewed or has something to add about the subject. And as mentioned earlier, Talking Head tries to unravel the mystery and mythology around an actor who worked with the masters of Indian cinema in the 1970s. The proximity and association that Dhritiman had with Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen helped create magic on screen. In that sense his two definitive roles are Ray’s Pratidwandi and Mrinal Sen’s Padatik. They were films representative of the volatility of the times. I think that’s what makes him interesting and his stories worth listening to. The characters he played with in the cinema of the 1970s remained somewhere inside him, disallowing him to be a mass figure. The total number of films that he has done is much lesser than any commercial actor in Bengal or India does. So in a way the narrative of his work with Ray is a kind of a subtext that runs through my film, but it is about the actor’s journey. It is about the duality that an actor like Dhritiman has, the private and the public persona. The constant escaping of the characters he performs and yet the falling into the skin of the memorable characters. And this is particular to Dhritiman because of his elusiveness.

7. Tell us something about the rationale for introducing the clippings of Bachchan’s films, Deya Neya, Piya Ka Ghar (he didn’t act in it, though he was offered) ... and the soundtrack incorporating songs like the ‘Jochhona korechhe’, ‘Listen to the falling rain’, and ending with ‘Jambalaya’.

Music has always been a very important part of all my work. In fact, compared to my earlier work, I’ve been very sparse in using music in Talking Head. The tracks are a part of the narrative and they all come from the vinyl collection of my father, who was an avid music and cinema lover. All tracks represent Calcutta during the time of Dhritiman’s film and advertising career. The Usha Iyer (Uthup) tracks resonate with Park Street of the ’70’s. The Amitabh Bachchan film clips are from Tinnu Anand’s directorial repertoire, and no story of Bengali cinema and actors can be complete without the enigma of Uttam Kumar.

All images courtesy: Spandan Banerjee

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)