On the 9th of February, 2018, a sub-30 seconds clip from a song of the then-upcoming Malayalam film Oru Adaar Love took India by storm and became viral on the social media almost overnight. Priya Prakash Varrier, the teenage actress who had featured in the clip, was catapulted to instant stardom and in its wake became a national crush and was soon dubbed as the ‘wink queen’.

Even if one is tempted to discount the phenomenon as a result of smart marketing, it cannot be denied that countless scriptwriters, lyricists and directors have often made room for at least one defining shot in an Indian mainstream and popular film that captures the mysterious and hypnotic hold of a heroine’s gaze – not only on the hero’s heart, but on the psyche of the audience as a whole.

When such a ‘look’ is interspersed with a song, the effect is beguiling and turns into a token of memory for cinephiles to hum across time. Popular cinema is adept at exploiting the effect and there are innumerable examples since the early days of Hindi cinema. The catalogue is vast. A few examples, however, would suffice to establish the point.

Addicts of yesteryears monochrome delights still recall K. L. Saigal’s Do naina matware tihare in Meri Bahen (1944) or the soulful rendition of the blind-singer K C Dey’s Baba man ki aankhen khol in Dhoop Chhaon (1935). Hemant Kumar’s Yeh nayan dare dare in Kohra (1964) is still a hit among contemporary listeners. But the gen-x has its favorites, too: Tere naina in My Name is Khan (2010) or Tere mast mast do nain in Dabang (2010).

K L Saigal's hit song Do naina matwale from the 1944 film Meri Bahen/My Sister.

The personal gaze transmutes into a political connotation in Utpalendu Chakraborty’s Chokh (1983) – a charged narrative that draws us into the disturbing but pertinent question: Whose eyes, see what? Om Puri’s piercing look raises the banner, a silent probing that draws in its fold the play of power and the deceit that goes into manipulating dissenting voices and how ‘the eye’ turns into a metaphor to ‘Look back in anger.’

Incidentally, Om Puri’s eyes have been a vehicle of many parallel filmmakers. Not without a reason. There is something primal, visceral and raw in the way the actor succeeds in articulating a spectrum of emotions through his eyes. His oeuvre is a testimony: recall the repressed rage in Ardh Satya (1983) or the impactful cameo in Gandhi (1982) or else, Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh (1980). Interestingly the feature that Puri has deployed so well was subverted in the dark comedy Jaane Bhi Do Yaron (1983) where he sports dark sunglasses to mask his eyes or in Sparsh (1980) where he plays a blind man along with Naseeruddin Shah – another actor per excellence whose vulnerable eyes in Gautam Ghosh’s Paar (1984), or the wry and romantic gaze in Mirza Galib, or the lustful stare in Mirch Masala (1987) – are indicators of his prowess.

Bollywood films, in contrast, have remained trapped in hyperbole where eyes reddened by anger or with the intent of settling scores are the staple. Even so, actors like Amrish Puri – often a victim of the comical and kitsch while utilizing his eyes as a communicating mode, transcends in his role as Mogambo in Mr. India (1987). His bulging eyes take on a new intensity and – extraordinarily – also a touch of humor – as he deliberates with his cohorts to outdo the invisible Mr. India. The pet saying that comes as a leitmotif throughout the film “Mogambo Khush Hua” acquires its effect because of the way he actually lets his eyes do the talking.

Beyond such hyperbole, Meena Kumari comes to mind. In the song Na jao saiyyan in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), she infuses both sadness and longing through her expressive eyes in a bid to restrain her husband from visiting his paramour.

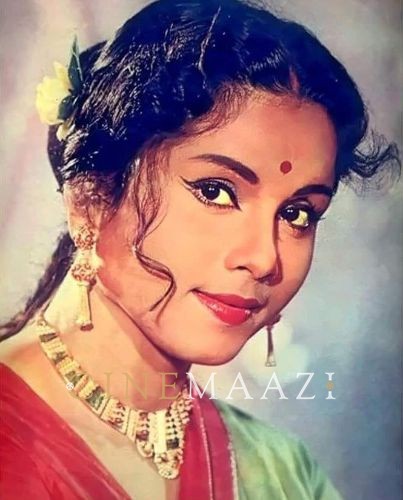

This mark of pitying vulnerability gets a sunny contrast in Madhubala where a mix of youthful vigour and playfulness in her twinkling eyes in Mr. and Mrs. 55 (1955) to her naughty smirk in Howrah Bridge (1958) or her enticing eyes in the song Ek ladki bheegi bhagi si express a touch of both of immediacy and ephemerality that still resonates among contemporary audience.

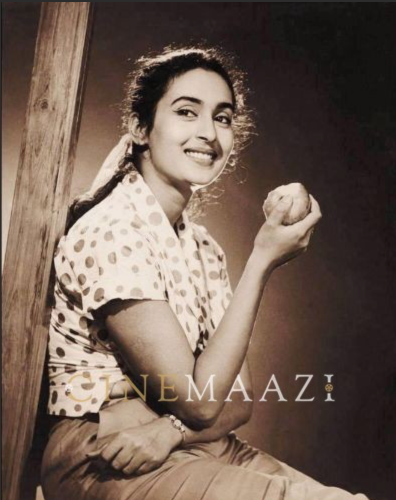

But if eyes are also a way to express giving or to convey the wish to be accepted, then few can contend with Nargis, at least in the context of mainstream cinema. She exudes a unique innocence through the darkness of her kohl-laden eyes.

Here, one might be tempted to pause and ask: Can Suchitra Sen be far behind? Well, she did have beautiful eyes, and yet often, she ended up giving them a touch of unreality and that’s because of the way she would cast her gaze – stylized (too often repetitive) at times unblinking and coupled with arched eyebrows along with a touch of pride irrespective of the demands of the narrative. Where she reigns in, partially at least, for example in Saat Paake Bandha (1963) or in Saptapadi (1961), the doe-eyed Bengali icon succeeds in skipping the audience’s heartbeats.

Madhubala's enticing looks and Kishore Kumar's playful eyes in the song Ek ladki bheegi bhagi si makes it an evergreen hit

In this context let’s not forget Smita Patil. Simple. Unaffected. Profound. And yet bristling with lust, anger or susceptibility – whatever the narrative demanded she could essay it with ease, regardless of the genre: commercial or otherwise. Her fearful eyes in Mirch Masala, her eyes of grit in Manthan (1976), her evocation of denial, acceptance and resistance as conveyed through her look in Arth (1982), Mandi (1983), Bhumika (1977) would remain a veritable repository of uncluttered acting.

Let’s shift focus and confront ourselves with a few directors beyond the national boundary.

The image that haunts us – will so for many decades to come – is the image of the sloshing of an eye in Luis Bunuel-Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou. Such nuanced excess isn’t palatable to all. Granted. But if the eye is the repository of multiple emotions then the grotesque is also its part. Hitchcock played with the eye as a window to convey both the apparent and the suggestive. Birds, for instance or Psycho when the 3-minute sequence involving Marion Crane driving in the rain to flee away with the money to the Bates Motel is replete with Janet Leigh’s expressions primarily in her eyes that underscore confused but heightened tension between the protagonists.

Voyeurism is an integral, even if a debased aspect of the act of looking. Hitchcock explores it in films like Rear Window. But then Narcissism? It, too, involves a flawed looking at the self, especially with a mirror before. To extend the metaphor, the camera lens can both turn into a voyeur and a mirror. In Ingmar Bergman’s Persona two characters deliver the same monologue, but separately, looking directly into the camera. In Camera Buff, after spending a prolong time looking at the ‘other’ the lead in final scene turns the gaze inwards, an act of looking that involves both his inward gaze and the camera’s reverse gaze on the looker through the viewfinder.

Yeh nain dare dare from Kohraa (1964) starring Waheeda Rehman and Biswajit. It was composed by Hemant Kumar

Diziga Vertov believed that as an extension of the human eye, the ‘technical eye’ of the camera lens could ‘see’ and record a truth that the ordinary human eye would fail to register. But in the end, the simple act of seeing is perhaps more profound. It would be a cause of celebration if, perchance, we can accommodate and balance the eyes of the doe with the stare of the cheetah, with the eyes of power with the eyes of denial, with the eyes of lust with the eyes of grace, the eyes of the human with the unblinking stare of an artificial eye.

This article was originally published in Silhouette Magazine on 3 July, 2018. It was co-authored by Shiladitya Sarkar. The images used in the feature are souced from the internet not taken from the original article.

Tags

About the Author

Amitava Nag is an independent film critic and editor of film magazine 'Silhouette' (www.silhouette-magazine.com) since 2001. Till date Amitava has authored 5 books on cinema including 'Satyajit Ray's Heroes and Heroines', '16 Frames' and 'Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Films of Soumitra Chatterjee'. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in Bengali and English and authored a collection of short stories each in English and Bengali, and an anthology of Bengali poems.His first anthology of English verses and a selected translation of Soumitra Chatterjee's poems are awaiting publication.

.jpg)