The Right Prescription: The Best On-Screen Doctors

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

With the pandemic ravaging lives and livelihoods, doctors have emerged as our lifelines, underlining what Seneca said, ‘People pay the doctor for his trouble, for his kindness they still remain in his debt.’ Over the last year and a half, real-life heroes wearing masks and scrubs have replaced caped superheroes of the Marvel and DC variety in our lives. On Doctor’s Day, commemorating the birth and death anniversaries of Dr Bidhan Chandra Ray, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at our most memorable doctors on screen, from the conscientious Dr Kotnis, the pioneering surgeon Neela in Chalachal, the dedicated doctors in Tapan Sinha’s films, to the anguished Babumoshai of Anand and the goofy Munna Bhai.

***

Indian films, particularly in Hindi and Bengali, have seldom got the depiction of specific professions right. Barring Ramesh Sharma’s New Delhi Times (1986), I cannot recall one Hindi film that paints an authentic picture of journalists and journalism. A far cry from films like All the President’s Men (1976), Zodiac (2007) and Spotlight (2015), to name only a few, that get the newsroom spot-on. Doctors fare no better. While a Munna Bhai MBBS (2003) works as a parable and features the kookiest of on-screen doctors in Dr Jagdish Asthana (Boman Irani) and a hoodlum-turned-wannabe-doctor Murli Prasad Sharma (Sanjay Dutt), Amitabh Bachchan’s tipsy surgeon Ram Prasad Ghayal in Mrityudata (1997), tripping into the operation theatre dead-drunk, represents the nadir, asking for an impossible suspension of disbelief.

Often described as the noblest of professions, the medical fraternity has more often than not received short shrift when it comes to the depiction of the lives and work of doctors. This is particularly true of Hindi films which have had no dearth of doctors as protagonists but have seldom delved into the inner workings of the profession, like English films such as The Doctor (starring William Hurt) or Awakenings (the Robin Williams/Robert de Niro film based on Oliver Sacks’s 1973 memoir about a neurologist who has discovered the benefits of the L-Dopa drug in ‘awakening’ patients with encephalitis lethargica) or even a full-fledged series, ER, have done. Bengali films have a better record in this regard thanks to the literary works of Banaphool (Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay) and Ashutosh Mukhopadhyay which have been immensely popular in their screen adaptations.

Dushman (1939)

Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946)

The one biopic around a doctor’s life that Hindi cinema has managed, V. Shantaram’s film Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani (1946) is based on the work of Dr Dwarkanath Kotnis. At the height of the Second World War, Dr Kotnis (Shantaram) learns that the Chinese, besieged by Japan, need medical help. The idealistic doctor travels to China and dedicates the rest of his life to the people there. He marries a local girl who had become his assistant and such is their zeal that they even spend their wedding night attending to the wounded. When the country is ravaged by a plague, the doctor not only strives to find a vaccine but also uses himself as a guinea pig to develop antibodies. Eventually he succumbs to the demands of the profession. Unlike the general run of our biopics, Shantaram keeps the film free of overt melodrama, thanks to some sharp writing by K.A. Abbas and V.P. Sathe, with V. Avdhoot’s cinematography and Vasant Desai’s music adding to the narrative. Though one can crib at the Chinese make-up given to Jayashree (who plays Ching Lan, a medical student disguised as a man and fleeing the bloody Nanking massacre) and Baburao Pendharkar (who plays General Fong, the head of an army unit) and a couple of meet-cute interactions between Kotnis and Ching, on the whole the film brings alive an incredible era of history when Indian doctors driven by a sense of commitment to their profession and humanity travelled to war-torn China to heal the dying and the wounded. The two nations have surely travelled a long way since then.

Anuradha (1960)

Dil Ek Mandir (1963)

This is a melodramatic four-hankie tearjerker typical of its era. As is expected of a film starring Meena Kumari and Rajendra Kumar, C.V. Sridhar’s 1963 film Dil Ek Mandir is basically an over-the-top love triangle with a doctor at the core. The names of the titular characters give an indication of what’s in store for the hapless viewer: the selfless doctor played by Rajendra Kumar is called Dharmesh (not surprisingly, as he is called to exercise his Dharma as a doctor time and again). He nurses a broken heart as his once-beloved Sita (Meena Kumari) has married Ram (Raaj Kumar), a rich businessman. When Ram is diagnosed with cancer, Sita brings him to Dharmesh’s hospital, but cannot convince herself that Dharmesh will set aside his feelings for her and cure Ram (as if characters named Ram and Sita could ever be separated by death!). If that’s an impossible notion to have about any doctor worth his scalpel, you need to just wait for the heavy hamming opportunities it allows the protagonists, as Dharmesh proves his dedication and successfully operates on Ram before conveniently passing away from overwork! Rajendra Kumar as the doctor is like Rajendra Kumar in any other film, lips a-aquiver and teary-eyed at the drop of a stethoscope, while Meena Kumari sheds copious tears, like only she could, all through this torturous outing.

Tere Mere Sapne (1971)

Dev Anand was never the best of actors and his brother Vijay Goldie Anand was more than just a director of rocking thrillers. With Tere Mere Sapne (1971) both brothers seem determined to prove their detractors wrong. Goldie was just coming off a white-hot streak with the blistering successes of Teesri Manzil (1966) and Jewel Thief (1967, which starred his brother), when he decided to adapt A.J. Cronin’s The Citadel (earlier made in Hollywood, starring Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell and Rex Harrison). Though dedicated to the medical community and starring Dev Anand as an idealistic doctor who takes up work at a village near a coal mine, the film is essentially an intimate tale of marriage and relationships. In the course of his work, Anand Kumar (Dev Anand) meets and falls in love with Nisha (Mumtaz, in the performance of her career). Dealing with the vicissitudes at work, his wife’s miscarriage and other misfortunes, Anand slowly lets go of his early idealism and trades it in for money. Things get complicated with the entry of the depressed film star (Hema Malini in a strong cameo) who falls in love with Anand, as the film changes focus from the medical to the personal.

Brimming with some brilliant songs composed by S.D. Burman, Tere Mere Sapne marked a welcome change of pace for the director who shows his penchant for dealing with strong human relationships while his brother delivers a performance devoid of his starry trappings. It also marked the last of the collaborations between the two brothers and is indeed the last film starring Dev Anand that is halfway watchable and does not make one squirm. The film was remade in Bangla as Jiban Saikate (1972) and starred Soumitra Chatterjee as the doctor, with Aparna Sen and Dilip Roy.

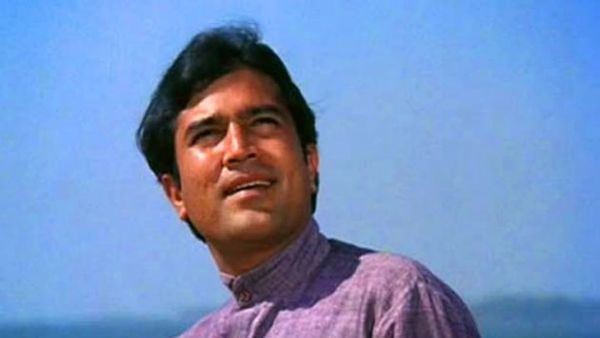

Anand (1971)

Hrishikesh Mukherjee created what is probably the most well-known doctor in Hindi cinema, Dr Bhaskar Banerjee aka Babumoshai. While I have serious issues about the merits of Anand as a film, there is no doubt that it is Amitabh Bachchan as the anguished doctor meditating on the futility of his life and profession who roots its maudlin melodrama to a measure of realism. And though we do not have almost any other doctor (barring Ramesh Deo) or any visuals of doctors at work in a hospital, and even though Rajesh Khanna, glowing in the pink of health, looks nothing like a cancer patient, the film’s philosophy and songs (if not its dubious artistic merits) and, above all, Babumoshai have become the stuff of film folklore.

The director’s Bemisal (a remake of Uttam Kumar’s celebrated hit Ami Se o Sakha (1975), based on Ashutosh Mukherjee’s novel of the same name) also featured Amitabh Bachchan as a pediatrician and Vinod Mehra as a general practitioner who opens a clinic and gets involved in shady medical practices. Despite being one of the few Hindi films that deals with the practice of illegal abortions, and despite having two doctors at the core of the narrative, Bemisal (and Ami Se o Sakha) too, like most films on this list, largely steers clear of the nuances of a doctor’s work-life, focusing instead on the emotional personal drama involving the protagonists.

***

Daktar (1941)

Bengali cinema has fared marginally better when it comes to the depiction of the medicine men and their environment. The Pankaj Mullick-Ahindra Choudhury vehicle Daktar (1941) is an example.

Based on the story ‘Teenpurush’ by Sailajananda Mukherjee and directed by Phani Majumdar and Subodh Mitra, the film, in keeping with the progressive ideals espoused by New Theatres, addresses social ills like untouchability and the need for doctors to head for the villages to provide healthcare for all. It also tackles the issue of woman’s emancipation when its protagonist marries an outcast Maya (Panna Rani), in the process incurring the wrath of his father who disowns him. The wife dies at childbirth and the distraught doctor hands over his new-born child to the family retainer and dedicates the rest of his life to battling the ills of disease, poverty and superstition among the people. Life comes a full circle when his son, brought up by his grandfather (unaware of grandson’s lineage), grows up to become a doctor and falls in love with a Christian.

There’s a charming earnestness to Pankaj Mullick’s dedicated doctor here that is hard not to admire even eighty years down the line. And there’s no denying the commitment to a socially conscious cinema as Amarnath goes around berating people for paying no heed to cleanliness, exhorting them to overcome blind religious beliefs, even taking on the local temple and its powerful priests for the unhygienic way in which they dispense charanamrit and prasad which then become a conduit for epidemics.

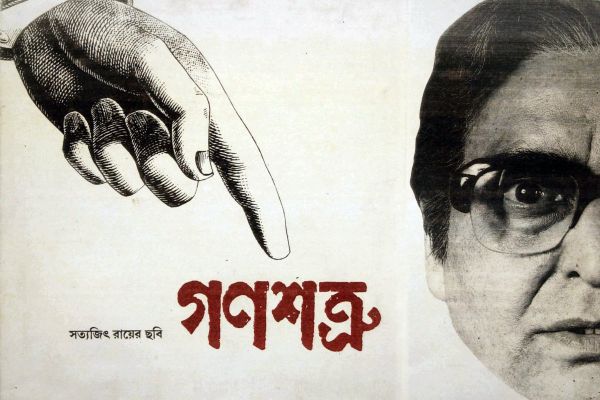

The Satyajit Ray Films

The manner in which Daktar addresses the issue of religion and science found its echoes in Satyajit Ray’s 1989 film Ganashatru, which too has a doctor as its protagonist. Generally considered as the weakest of Ray’s films, it deals with the efforts of a conscientious doctor, played by Soumitra Chatterjee, to highlight the dangers of an impending epidemic arising from the local temple’s charanamrit being polluted due to poor underground sewage pipelines. Uncharacteristically shoddy (for a film by Ray) in terms of its technical aspects, the film, despite its very topical message of religious superstition, suffers from verbosity and static camerawork which rob it of the effect one associates with a Ray film.

Another Ray script with a doctor at its core, this one directed by his son Sandip Ray, is Uttaran (1994). It again stars Soumitra Chatterjee as a doctor, Nihar Sengupta, who has lost touch with the basic values that should drive a doctor’s work. His clientele comprises a wealthy, neurotic, urban lot who have all the money for their imagined illnesses. On his way to deliver a lecture on the progress in medical research, Dr Sengupta’s car breaks down near a remote village. It is here that the doctor is exposed to the realities of medical care, or lack thereof, in the hinterland and experiences an awakening of conscience. A middling affair, often ham-handed, the film benefits largely from a characteristic strong performance by Soumitra Chatterjee but has little else to offer.

Uttam Kumar as a Doctor: Ananda Ashram (1977) and Agnishwar (1975)

Shakti Samanta remade Daktar in 1977 as Ananda Ashram (like Daktar, this was made simultaneously in both Hindi and Bengali), starring Uttam Kumar, Sharmila Tagore, Utpal Dutt and Ashok Kumar. Here, the caste angle of the original makes way for religion (another determinant of one’s caste) with Asha’s (Sharmila Tagore), the heroine, Christian roots (her father, once a high-caste Brahmin, is rendered an outcaste from Hindu society after he marries a widow and converts to Christianity). There are other subtle changes, like the addition of a childhood backstory to the Asha-Amaresh (Uttam Kumar) relationship.

Uttam Kumar is sublime as the irascible, idealistic doctor in Arabinda Mukherjee’s Agnishwar, an adaptation of well-known author Banaphool’s (incidentally, the director’s brother) novel Agni, based on the life of his teacher Dr Agnishwar Mukherjee. As the egoistical, no-nonsense doctor who never hesitates to speak his mind and who learns a lesson in humility after the death of his wife and in his interactions with the poorest of the poor, Uttam Kumar is a towering presence with his piercing look, spectacles perched low on his nose. This is one of the rare films that actually show a doctor in his work environment to make for a very authentic portrayal.

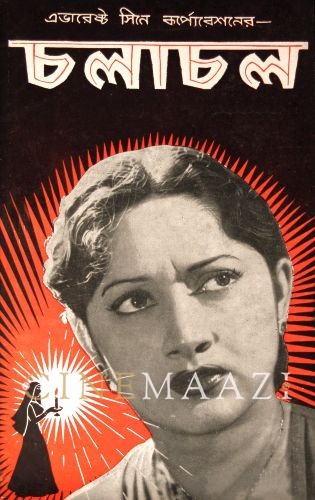

The Women: Chalachal (1956) / Safar (1970) and Deep Jweley Jaai (1959) / Khamoshi (1970)

There’s a reason to look at Chalachal / Safar and Deep Jweley Jaai / Khamoshi together, apart from the fact that both were directed by Asit Sen. Based on stories written by Ashutosh Mukherjee, these films created the definitive black-and-white look of Bengali cinema of the era, pioneered by filmmakers like Sen and Ajoy Kar. While focusing on the personal and emotional upheavals that the protagonists go through, the films address the hospital environment in greater depth than a lot of our films dealing with medical issues and does it with a lot of attention to detail (though it can well be argued whether any medical practitioner will be asked to take on the kind of responsibility Nurse Radha is in Deep Jweley Jaai). Both films have as their protagonist a woman – a nurse (Suchitra Sen/Waheeda Rehman) in Deep Jweley Jaai / Khamoshi and a doctor/surgeon (Arundhati Devi/Sharmila Tagore) in Chalachal / Safar – and in that sense created pioneering working-women characters in cinema.

Chalachal stars Arundhati Devi as Neela, a surgeon who befriends the terminally ill painter Avinash and is influenced by him to marry a businessman with tragic consequences all round. With Rajesh Khanna stepping in to play Avinash in the remake, it isn’t surprising that the focus shifts from Neela in Safar. Chalachal on the other hand is all the way an Arundhati Devi vehicle, with the actor at the peak of her imperious histrionic best. Though Sharmila Tagore has one of the finest roles of her career, Safar adds a lot more to Avinash than the original had, including philosophical musings and two of Hindi film’s great songs in ‘Zindagi ka safar’ and ‘Jeevan se bhari’. I for one feel that in shifting the focus from Neela and in the change from black and white to colour, Safar loses out on the psychological underpinnings of Chalachal.

Khamoshi has Rajesh Khanna in what is an extended cameo and he does a much better job of it than Basanta Chaudhuri in the original. However, if the remake suffers in comparison to the original despite its superlative music score, it is solely due to Suchitra Sen. Considered by many as the film that defined her, Deep Jweley Jaai, based on Ashutosh Mukherjee’s story ‘Nurse Mitra’, explores the relationship between a nurse and a patient entrusted to her care. As a psychiatric nurse in a mental hospital who falls in love with a patient and slowly loses her own sanity, Suchitra Sen is pure dynamite in a heroine-oriented film, with the climax still counting as one of the most celebrated sequences in popular Bengali cinema. Though this is arguably her finest hour after Guide, Waheeda Rehman in Khamoshi never quite measures up to Suchitra Sen and that in essence proves the film’s only, and probably fatal, failing vis-à-vis the original.

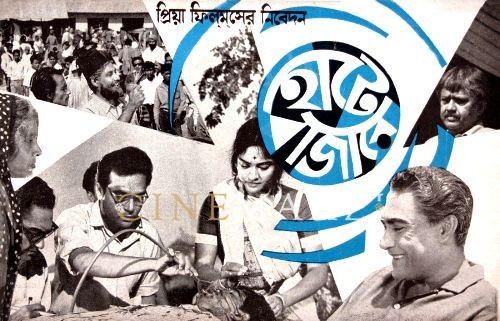

The Tapan Sinha Films

But by far the filmmaker who has provided the most authentic depiction of doctors and their work is Tapan Sinha. From Kshaniker Atithi (1959) to Wheel Chair (1994), Sinha created some of the best on-screen doctors.

Based on a story the director himself wrote under the pseudonym Nirmal Kumar Sengupta, Kshaniker Atithi narrates the story of a doctor, Bimal (Nirmal Kumar), who devotes himself to the welfare of people in a village. There’s an elegiac lyricism to the film underscored by two understated performances by Nirmal Kumar and Ruma Guha Thakurta. But what sets the film apart is the time and space the director allows in bringing out the world of a doctor. Here is a doctor actually shown moving around his patients, attending to their distress in his ill-equipped hospital. The patients in the hospital make for what Bimal memorably describes as ‘a microcosm of Saratchandra’s world’ – and it is this embracing of an environment beyond that of the protagonist that makes this a classic portrayal of a doctor’s world. Tapan Sinha remade the film as Zindagi Zindagi (1972) starring Sunil Dutt. The Hindi version – barring the brilliant Kishore Kumar songs ‘Teri zaat kya hai’ and ‘Tuney hamein kya diya ri’ – however never manages to convey the poetic essence of the original, and is undone by the addition of unnecessary subplots to cater to a larger audience and a happy ending that simply does not work.

Ek Doctor Ki Maut (1991), boasting a career-best performance by Pankaj Kapur, is another class act dealing with doctors and the world of scientific research. Based on Ramapada Chaudhuri’s Abhimanyu, the film is inspired by the real-life story of Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay who pioneered research in the field of in-vitro fertilization in India. However, bureaucratic wrangling and ridicule in the scientific community, arising out of professional jealousy, prevented him from sharing his research, and from being acknowledged as the first person to successfully complete the IVF process, a recognition that went to the UK’s Louise Brown. His life’s work coming to naught, Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay took his own life. Ek Doctor Ki Maut is an uncompromising look at what ails scientific research in India, as the director creates a despairing and often-frightening scenario of bureaucratic red-tapism and professional rivalry. Though, unlike the fate that befell Dr Mukhopadhyay, Tapan Sinha ends the film on a note of hope, it remains a searing indictment of academics in India, riven by politics and bureaucracy, and which can easily be applied to all creative endeavours in this country.

The other film in Sinha’s oeuvre of doctor protagonists is Arohi (1965), based on Banaphool’s short story ‘Arjun Mandal’. Though hugely feted at international and national film circles – winning the President's Silver Medal for Best Feature Film (Bengali) at the twelfth National Film Awards and an award at the 1965 Locarno Film Festival – it is unfortunately unavailable either on disc or on YouTube. One can only get a sense of the film and Kali Banerjee’s much talked-about performance in the lead as Arjun Mandal from Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1976 remake Arjun Pandit.

Sanjeev Kumar (in the titular role) plays an unlettered henchman for the local zamindar whose life changes after his interaction with the district doctor, played by Ashok Kumar. Though the film deals with the doctor’s life only tangentially through that of Arjun’s, the film occupies an important place in Sinha’s oeuvre. However, despite a Filmfare-Award-Winning performance (as best actor) by Sanjeev Kumar (in an atrocious wig), and despite winning the award for best story, with Bindu, as the doctor’s wife, being nominated for best supporting actress, Arjun Pandit is far from Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s best.

Way too long even at a little over two hours, done in by an excess of maudlin sentimentality, even the comedy, uncharacteristically for Mukherjee, falls flat. Though there’s something to be said for watching Ashok Kumar, Sanjeev Kumar, Vinod Mehra and Deven Verma in one frame (none of them alive anymore), or Ashok Kumar singing ‘Main bann ki chidiya’ or Gulzar’s dialogue incorporating a translation of Sukumar Ray’s nonsense verse ‘Ramgorurer chhana’ – Ramgoru ke bachhe, kaan ke bahut kachhe – the only reason that makes watching Arjun Pandit worth the while is to get an idea of what Arohi could be like.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)