The Perils of Adaptation: Feluda Pherot

Srijit Mukherji’s take on Bengal’s most loved fictional detective is an enjoyable ride that harks back to the childhood memories of an entire generation even if it fails to blaze a new trail. Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri looks at the film and the pitfalls of adapting Feluda…

I have been struggling with this for a while, putting it off, trying to work out in my mind what this latest adaptation of a Feluda story signifies – apart from bringing back the franchise six years after Sandip Ray’s Badshahi Angti (2014). The task is made even more difficult given that everyone and their grandmother is an expert on Feluda and has an opinion on how the stories should be adapted, and the challenges that entails. The reactions to Feluda Pherot Season 1 have ranged from the one extreme of unbridled excitement and hyperbole about one of Bengal’s most successful contemporary directors, Srijit Mukherji, adapting a Feluda story to a lot of hand-wringing about him ‘playing it too safe’ to be able to break any new ground.

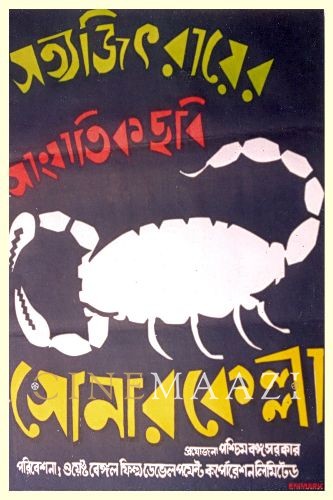

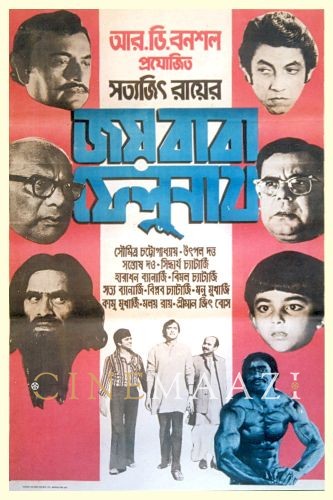

To begin with, one needs to bear in mind that it’s not just Srijit who has ‘played safe’ with Feluda. Sandip Ray himself, in the course of his seven Feluda films – starting with Bombayer Bombete (2003), almost twenty-five years after Satyajit Ray’s Joi Baba Felunath (1978) – rarely went beyond the text. Despite his attempt to contemporize the stories – questioning the relevance of Sidhu jyetha in an age of Google search, more tokenism than a genuine belief in the need to update the series – I never quite took to his adaptations apart from Bombayer Bombete and Badshahi Angti, and those too primarily because of the prospect of seeing Sabyasachi Chakraborty and Abir Chatterjee as Feluda. The films were too staid, too conservative, too respectful in their approach to the original text to excite enthusiasm once the novelty of a new actor playing Feluda had worn off. It is as if the filmmaker, even though he is Satyajit Ray’s son, was wary of making even the kind of changes Satyajit Ray himself had made to the novels Sonar Kella and Joi Baba Felunath, or for that matter, in his cinematic adaptations, say, Charulata or Aranyer Din Ratri, to name just a couple. I wonder how much of this reluctance to attempt a makeover of Feluda stems from a perceived backlash from the core fan base of Satyajit Ray’s iconic detective. (This disinclination to go ‘beyond the text’ is what marred Sandip Ray’s adaptation of the first Shonku story to be filmed, Shonku O El Dorado – which remained a straightforward and unimaginative rendition of the text at best.)

In the end what makes Feluda Pherot: Chhinnamastar Obhishap enjoyable, despite its unwillingness and inability to create a new template, is Srijit’s feel for and obvious delight in the original. Each frame seems composed with a quiet reverence for a master – often echoing sequence in both the Satyajit Ray films. His almost childlike enthusiasm in ‘recreating’ the text cannot but infect you so that you give up expectations of any reinvention and willingly go with the flow.

In an era of SUVs and snazzy cars, GPS and iPhones, five-star holiday resorts, PlayStation as hobbies, the world of Feluda Pherot is a throwback to a more innocent time. Till the time we have the nerve and the imagination to give Feluda a complete transformation, making him grow out of his adolescent fan base, explore his psychology and (why not?) sexuality, till the time we realize that a reinterpretation is probably a better tribute than a faithful rendering, Feluda Pherot – with its Ambassador cars, ornate telephones, a travelling circus, the romance of circuit houses and bungalows in mofussil towns, philately, riddles and word games – is just the comfort food you would love to munch on.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)