Oka Oorie Katha: Mrinal Sen's 'Savage Prophets'

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Based on Premchand’s ‘Kafan’, Mrinal Sen’s Telugu film is as much an exposition of his unwillingness to settle for easy comfortable storytelling as it is an insight into his approach in adapting a literary work to screen, Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri writes…

‘In India where except in a few cases, film-makers have hardly looked beyond what their predecessors had achieved, we need … experiments to enlarge the area of operation, experiments to mark the advent of a new genre of cinema, experiments, above all, to sharpen the medium as an instrument of social change.’ – Mrinal Sen

The year was 1993 and Mrinal Sen’s Antareen had just been screened at the Calcutta International Film Festival. The film’s credit titles mentioned that the film originated ‘from an idea based on a story by Sadat Haasan Manto’. A journalist at a press conference asked Sen the title of the Manto story that had inspired the film. Instead of answering the journalist, Sen said, ‘Please go through the collected works of Manto and tell me the title of the story you think has served as the basis of my film.’

As everyone acquainted with Premchand’s story knows, it is set in a bitterly cold winter night in a village in Uttar Pradesh. A father-son pair sit outside their ramshackle hut roasting potatoes they have stolen from the zamindar’s fields, while inside the hut the son’s wife is going through the pangs of childbirth. It is the woman who has been their source of livelihood all this time, but the indolent men are too far gone to do anything to come to her help. They gorge on the potatoes, trying to hoodwink each other for the lion’s share, and fall asleep. By morning, the woman is dead. The father and son go out begging for money for the last rites but having collected the money they go to the local hooch shop, get drunk, all the time philosophizing about the vicissitudes of life while the woman’s corpse lies rotting.

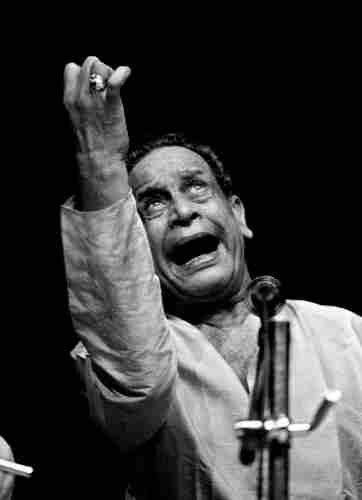

Unlike Premchand’s story which ends with the father and son singing and dancing in the tavern, Sen creates a coda. Venkaiah stands under a tree, clutching the money in his hand, demanding food, clothes and a house again and again, ultimately screaming, ‘Bring her back.’ At this stage, Sen does the unthinkable – Nilamma’s face dissolves while flames envelop the screen – in a graphic exposition of Venkaiah’s pent-up and suppressed anger. In the words of Sen’s biographer Dipankar Mukhopadhyay, ‘Critics have commented upon a Brechtian dimension in his character. Sen calls him sort of a Monsieur Verdoux, an absurdist extension of a trade union leader … [full of] anger and sarcasm.’

The film left me feeling angry and sad and, more important, helpless, which finally gave way to horrified awe at the director’s ability to craft a philosophy so insidious. Sen could be the cruellest of storytellers on-screen. Not for him innocent, safe storytelling. From Baishey Shravana to Calcutta 71 to Kharij he believed in confronting the viewer with their inherent hypocrisies. Oka Oorie Katha does that and there is no way you can emerge from it without being shaken, questioning your beliefs. Somehow, with the horror stories emerging from the woes of migrant workers all over India in the wake of the lockdown, the film is alive with a new resonance.

Postscript: The film was screened at the first-ever Indian Panorama in 1978 in Madras. Sen invited Satyajit Ray to the screening. However, Ray was reluctant to come as the film had not been subtitled (it became mandatory from the year after) and Ray was afraid that he would not understand a word. Sen managed to persuade Ray to sit in for a while. After the screening, Ray hailed him, shaking his hands, ‘Thank you for persuading me. I would have really missed something.’

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)