Bengali in the Forefront

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Early in the history of cinema in India Bengal had earned a reputation of being in the forefront among other regional cinemas. Not on the count of numbers of films made but for its artistic good taste and narrative appeal.

Both were the products of the upsurge in literature, arts, education, social reform and scientific enquiry that Bengal experienced in the nineteenth century. The inheritance of this so-called Renaissance rubbed off on the new craft of filmmaking, which by the twenties of this century had improved sufficiently to make story-based films. Even in those early years many educated persons, some of renown among them, became actively associated with the making of films or took a thoughtful interest in it. Persons like Pramathes Barua, Nitin Bose, B.N Sircar and others gave up the callings and vocations their background and training prepared them for, to devote their time and skills to film-making. How keen was the interest taken by the intelligentsia in cinema can be gauged by an illustrative example. As early as 1929 Tagore saw its possibilities as an art form and communicator, and deplored in a widely quoted letter its crippling dependence on literary and other supports.

The Bengali middle class had grown and prospered because of various socio-economic and historical reasons. It became the natural leader of Bengali life and thought in the period of efflorescence referred to earlier. Its decline had not set in when in the thirties, sound and talkies put an end to the period of silent films. The interest and spirit of enquiry which the middle class had shown in cinema became keener, its involvement wider and deeper. Besides providing a major share of spectator patronage it brought to cinema elements of its cultural and intellectual inheritance. But the involvement also meant that it brought to filmmaking its predilections and biases.

Two traits of those were a love of literature and enthusiasm for theatre. Abundance of fictional material afforded filmmakers a wide choice of stories to base their films on. This led to a reliance on and adoption of literary modes of exposition. It is worth noting that well-known writers like Premendra Mitra, Sailajananda Mukhopadhyay and Premankur Atarthy became closely associated with cinema as script writers and directors.

The influence of theatre was even less felicitous. Talkies gave ample scope which was eagerly utilised for theatrical dialogues and dramatic acting styles. The impressive list of stage actors and actresses including the great Sisir Bhaduri who were contracted to act or even direct films shows how Bengali cinema looked to theatre for support.

Add to the crutches of literature and theatre a third one of songs and one can see the pitfalls that lay in the path of Bengali cinema's progress.

If despite them Bengali cinema forged ahead of other commercially bigger regional cinemas, it was because of several factors: technical competence, a growing awareness, dim as it was, that theatre's ways and profusion of songs were impediments instead of aids to cinema, stories by eminent writers, good taste and the support of the middle class were largely responsible for Bengali cinema's progress and reputation in the thirties and forties. However, all these might not have been of much avail if it did not also have the advantage of the model of a well-run and equipped studio built and managed by B.N Sircar, a person of vision and exceptional managerial abilities.

By the early fifties, however, most of the shine of Bengali cinema had worn off, exposing its weaknesses. The emergence of the matinee idol pair Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen, ensured spectator support but could not hide the deficiencies to a growing section of thinking viewers. They had become aware of cinema's expanding horizon and expressive power. They saw that for all its narrative appeal even the above average Bengali film was sentimental, wordy and painfully distanced from psychological and social reality.

The social and economic realities of post-independence partitioned Bengal were too grim not to generate anger and protest, and a search for cinematic ways to express them. In the field of the other arts rejection of established norms and exploration of untrodden paths had taken place yielding fruitful results.

Indications that there indeed were stirrings to break away from set ideas of form and content was seen in such films as Bimal Roy's Udayer Pathe (1944), Nemai Ghosh's Chinnamul (1951) and Ritwik Ghatak's Nagarik (1952). Ghatak's film was not released but the fact of his making a film depicting the pauperisation of a refugee family is a pointer to the undercurrents of ferment and striving. A few Hindi films like Uday Shankar's Kalpana (1948) and Bimal Roy's Do Bigha Zamin (1953) caused excitement among viewers in Calcutta. Brief exposure to European and Japanese cinema in the first international film festival in 1952 added to the excitement. The very few off-beat Bengali films made reflected the disquiet and the excitement. They were laudable efforts but they showed that their makers were steps away from fully grasping the authentic language of cinema. When that was seen to have been done, and in a first film at that, a true divide was drawn and a big leap forward taken.

Pather Panchali, released for public viewing in Calcutta in August, 1955, first bewildered and then overwhelmed the public, the average as much as the discerning viewer. Over the years, until his death in 1992, Satyajit Ray created a body of work which has ensured him a secure place among the greats of world cinema. It appears in retrospect that the right person appeared at the right time to make the most important landmark in the history of Indian cinema bestowing in the process incalculable benefits and prestige on Bengali cinema.

Satyajit Ray and his work may appear to some as overwritten subjects. It may occur to others that they have not been written enough about. If all has been written in many languages about his life, his creative output and facets of his personality were to be collected it would fill shelves. Yet the analytic and interpretative studies that continue to engage students and aficionados of cinema would suggest that there are areas and aspects of his work awaiting discovery.

Facts about Satyajit Ray's life and background are more or less known. Even so a few bear repetition if only to underline a point not always remembered. His background for instance. He had the advantage of a singular combination of circumstances to make him the right man at the right time and place to achieve what he did.

Writing on Japanese cinema Ray noted in an article his reaction on seeing Roshomon which, incidentally, was the first ever Japanese film screened in Calcutta. He wrote: "It was the kind of film that immediately suggests a culmination, a fruition rather than a beginning. You could not as a filmmaking nation have Roshomon and nothing to show before it." It is a thought that Pather Panchali seems to refute his observation. Bengali cinema might have been ahead for two decades and more of cinema in other filmmaking regions in India. But did it have much to show? Not really Thus in a way Pather Panchali was a beginning and not a culmination.

How did it happen? There is, of course, the unsolvable mystery of inborn gifts. That apart, the genetic and environmental advantages that Ray had seem to have been designed to nurture and bring them to fruition.

Satyajit Ray's grandfather Upendrakishore Ray and father Sukumar Ray were among the finest products of the nineteenth century resurgence in Bengal. The range of their interest and creativity in literature, graphic arts, printing technology and science were rare even in an era crowded with great names. For a person who would apply in future his faculties to acts of creation in what has been called the dominant art form of this century, the inheritance was of immeasurable value. So was the ambience of his childhood and the congenial atmosphere and opportunities in Calcutta to pursue and develop his interest in Indian and European music, painting, literature and typography. Discovery of and reverence for Indian's artistic heritage in the Santiniketan years ensured that roots in his native soil would never dry up. Work as art designer and illustrator for advertising copy and books, intense love for cinema, fitful viewings of classic films and then the first real exposure to world cinema in London (a hundred films in a five months' stay) — there you have the ingredients for the right mix. Additionally, were the lessons of Bengali cinema which, he once remarked, taught him how not to make a film.

After the Apu trilogy his work has been discussed by many critics in Europe and America. Most have elaborated the view that central to his beliefs are humanism, a modern outlook and understanding of the processes of change in traditional societies.

In recent years Ray's films are being studied in supposedly greater depth within a wider framework of reference. In them a noticeable tendency is application and use of criteria and arcane terminology of modern psychology, post-structuralism, social anthropology and semiology, not to mention Marxism, sociology, etc. Doubtless they have their value. But I wish to make two points arising out of them.

The first is that in appraisals of Ray's outlook and his work most European and American critics and students of cinema apply standards of aesthetic judgement developed in the West. There is an apparent lack of interest in analysing and connecting the emotive content and formal structures to Indian theories of art and indices of appreciation. Such an interest would balance to some extent the emphasis given to western role-modelling in Ray's films. When critics in western countries find more of Renoir, De Sica, Mozart and Chekhov in Ray's films they are prone to neglect his Indian, more specifically Bengali, sensibilities as sources of inspiration.

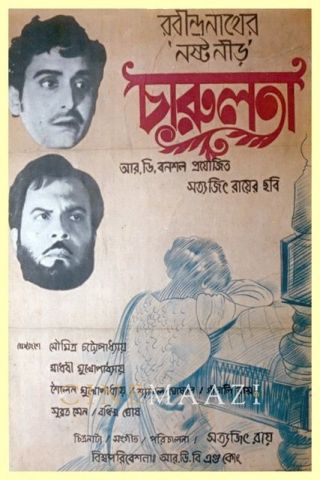

I would refer to two examples to substantiate my point. When Robin Wood in his book The Apu Trilogy remarks that "this (in Charulata, 1964) emotional complexity, the delicate balancing of responses, what one may call the Mozartian aspect of Ray's art, which links him with Renoir, is already characteristic in Pather Panchali," he leaves out Bibhuti Bhusan Bannerji, Indian musical forms and nature's role and significance in lives as lived in a Bengali village.

The second example is from Edwin Gerow's book on Sanskrit drama. He observes there that Ray's films "do not seem to respond to any Indian need at all" and "they are difficult to account for in (Indian) classical terms" and are "therefore in a technical sense tasteless" One wonders if a knowledge of the Bengali mind and milieu is considered unnecessary in appreciating Ray's films and what taste is made up of. Similarly, preoccupation with culture specifics in evaluating films often leads to bizarre misjudgements. Thus, Sita Kalyanam is highly praised by western critics and Ginsberg finds Sampurna Ramayana more insightful than Pather Panchali. Another trend is a search for subtexts and analysis of constructs. They do not necessarily help.

The second point is that there is a misconception that Ray's films have not been popular in India and have been appreciated only by western audiences. This is incorrect, certainly so in Bengal. Viewers went wild over Pather Panchali long before it won an award at the Cannes festival without the benefit of analytical studies by western observers. Ray himself never tired of saying that he made films with the audience at home in mind. The targeted audience nearly always responded.

The lead that Satyajit Ray gave to Bengali cinema with Pather Panchali instituted courage and confidence to young aspiring filmmakers to make films to express their dissenting mood and ideas. Ray was without question the primary cause of a fresh and feverish burst of creative activity in Bengali cinema.

The most venturesome of those who struck out on their own was also the most original in his outlook and methods. Ritwik Ghatak was not influenced by Ray, not overtly. This first film to be released for public viewing, Ajantrik (1958), showed his originality. It was evident that his imagination and concerns were of a different kind from Ray's. If the film he completed just about the time Ray began shooting Pather Panchali showed his concern for the disintegration caused by the partition of India in 1947, he projected in Ajantrik his discernment that the same process was at work in post-independence India.

Ritwik Ghatak's later films laid bare the compelling drives behind his passion and his pain, as much as his desperate search for abiding roots. The release that he sought from the prison house of memories and the brutal reality he faced found expression in haunting imageries of nature and dramatic situations in his films. They also reveal his faith in the mythic attributes of the supreme mother goddess, which were for him a psychological need to find roots deep and strong enough to withstand the turbulence and ruin he found all around.

%20(1).jpg/1%20(8)%20(1)__600x413.jpg)

More than others Ritwik Ghatak personified the Bengali ethos. It is difficult to explain why his films, almost all of them, were box office failures. The only solution to the paradox I can think of is that he was too unconventional and erratic in his technique and style to gain acceptance. The reference points of his films appeared obscure and confusing. He was perhaps ahead of his times, a Meghe Dhaka Tara /A Star covered by Clouds (1960) in his lifetime. It is only recently that the extraordinary qualities of his films are being appreciated and his worth as one of the most significant directors of Bengali cinema acknowledged.

If Ritwik Ghatak's films were box office failures, so have been many of Mrinal Sen's. But there the resemblance ends. Mrinal Sen has generally been regarded as the leading proponent of political cinema in India. But in his espousal of causes or depiction of reality he has been free from Ghatak's obsessions and fixations. His Marxist views and penchant for experimentation did not deflect him from his resolve to explore the psychology of individuals nor blunt while doing so his protesting social conscience.

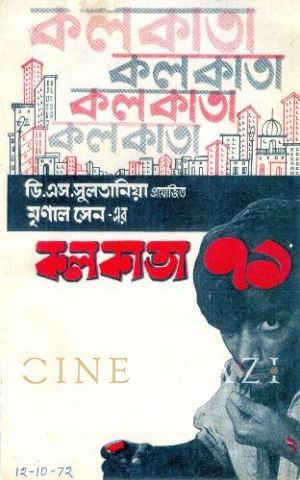

From his third film, Baishey Sravan (1960) onwards Mrinal Sen's control over the craft of filmmaking was evident. And so was his irrepressible urge to experiment with the ways of cinematic expression. His long career in films has helped in no small degree in enhancing Bengali cinema's reputation and its claim to be counted in world cinema. One does not become internationally the best known Indian film director without sufficient reason and justification.

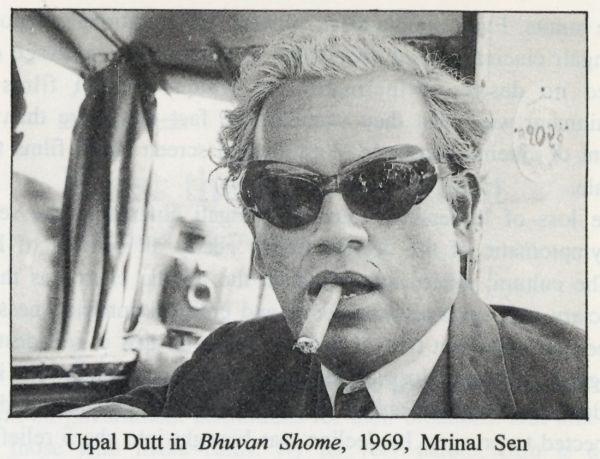

Mrinal Sen's career graph shows wide fluctuations. It reflects the variety of his films in both thematic content and formal experiments. He has been concerned as much with personal relationships, under-currents of middle class familial tension-ridden existence as with social issues like destitution, decay, struggle and political activism. He has not been afraid to cross linguistic barriers, one fruitful result of which has been Bhuvan Shome (1969) in Hindi, generally regarded as the precursor of parallel cinema in that language.

Many of Mrinal Sen's films can be faulted for their structural imbalance and hasty eagerness to break narrative moulds. Many of them, on the other hand, are memorable creations. There can, in any case, be no question, that his contribution to Bengali cinema has been. immense. What is particularly remarkable and welcome is the fact that making films for well over three decades now he shows no sign of tiredness or waning of his innovative imagination.

The primacy Bengali cinema had regained with Pather Panchali remained for nearly two decades. Others besides Ray, Ghatak and Sen contributed to its vigour Tapan Sinha, Rajen Tarafdar, Asit Sen, Barin Saha are some of the names that come to mind in this regard. Their thematic ideas and handling of the craft differed in depth and competence. But collectively they sustained the strength and vitality of what after all was minority cinema.

By the mid-seventies the vigour was gone. Ritwik Ghatak had not made a film for ten years. Many like Rajen Tarafdar and Barin Saha just dried up. Asit Sen migrated to Bombay. Only Tapan Sinha demonstrated his staying power and self-assurance. By charting and consistently following a middle path he ensured a measure of popular support for good cinema at a time when but for Ray's eminence and Sen's courage Bengali cinema might well have been relegated to a minor position.

In the seventies the commercial or mainstream Bengali cinema was in dire straits. Even middle-class viewers, the traditional support base of Bengali cinema, turned away The expanded class of wage earners showed no desire or inclination to watch Bengali films when entertainment was what they wanted. The fact that more than eighty per cent of cinema houses in West Bengal screen Hindi films tells its own tale.

The loss of leadership status of Bengali cinema in the seventies was symptomatic of the decline the in nearly all spheres of Bengali life. The cultural inheritance of which the middle class was the chief beneficiary was spent and the social and political consciousness which has been an important trait in Bengali character lost in self-destructive ideological strife and loss of direction. What remained were isolated individual talent and endeavour In such a situation cinema could hardly be expected to prosper. Its decline was brought into sharp relief by the enormous strides taken meanwhile by other regional cinemas of India.

Paradoxically, interest in serious cinema grew The number of film societies swelled and film festivals, big and small, have become regular events drawing huge crowds. Governments and institutional agencies began providing finance and other facilities.

As a result of these, a few young filmmakers, unburdened of the baggage of the past and anxious to move out of the shadows cast by Ray and Sen made some notable films in the eighties. Aparna Sen, Goutam Ghose, Utpalendu Chakraborty and above all Buddhadeb Dasgupta have refurbished to some extent the faded image of Bengali cinema. They have won critical acclaim in India and abroad and, a few of their films, spectator support in Bengal as well. However, the sobering thought is that they have depended mostly on state institution-al patronage. Can they continue to do so without damage to their independence and creative energy?

In 1995 countless functions will be held in filmmaking countries to celebrate one hundred years of cinema, and Bengali cinema will observe its seventy-fifth anniversary If one ruminates over what it has achieved, its ups and downs, its successes and failures during seventy-five years of its existence one is assailed by mixed feelings of pride and elation, dejection and despair. My personal misgivings arise from the evidence of near-complete erosion of cherished values and coarsening of the Bengali mind and sensibilities.

This article was originally published in the book Frames of Mind-Reflections Of Indian Cinema, edited by Aruna Vasudev. The images used were taken from Cinemaazi archive, the original essay and the internet.

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)