The Bard in Hindi Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Shakespeare wrote, ‘All the world’s a stage…’ In the over four centuries since he wrote those lines, perhaps they can be modified to read, ‘All the world’s my stage.’ His plays have transcended barriers of geography and time, and have lent themselves to adaptations in different languages in different settings in different lands.

What makes Shakespeare so popular, especially to Indian audiences? Is it merely, as some critics posit, an urge to be seen as ‘highbrow’? If so, there’s delicious irony in the fact that in his own time, Shakespeare wrote mostly for the layman. The beautiful wordplay and deep philosophies that he espoused mingled freely with farting jokes and puns. Both classes and masses would discover in these plays something that resonated with them.

His universal appeal lies in the familiarity of his themes and tropes – star-crossed lovers and separated twins, loyal friends and jealous courtiers, palace intrigues and treachery, ghosts and witches, drama and melodrama. Indian ‘Shakespeares’, therefore, became an amalgamation of current dramatic tropes and Shakespearean characters, cloaked in disparate forms at disparate times. Whether you call them ‘adaptations’ or ‘inspirations’ or something-in-between, Shakespeare had found a firm stronghold in Indian entertainment, performed in venues as diverse as stage, film, radio, folk theatre and digital medium.

The Bard first made his way into India through the medium of stage – mainly in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai). While Shakespeare’s historical plays were rooted in the milieu and the specific history of England, and did not readily lend themselves to being adapted to suit the Indian milieu, playwrights faithfully translated Shakespeare’s tragedies and comedies into the vernacular, while at the same time successfully transposing Shakespearean characters to Indian soil.

For instance, Cymbeline was first adapted for the stage by the National Theatre in Calcutta. The play, titled Kusum Kumari, was staged in 1874. Cymbeline also became the inspiration for another play titled Champraj Hado. Staged in 1884, this version would blend Shakespeare’s tale with elements of Rajput folklore, with the drama set in a Mughal court.

Film adaptations followed. In 1923, Nanubhai Desai would transpose Champraj Hado to the silent screen, while a ‘talkie’ version named Sati Sone or Sona Rani, directed by Madanraj Vakil, released in 1932. These were not the only stage or screen adaptations of this play. The Parsi Theatre in Bombay adapted Cymbeline as Meetha Zahar in 1900. In 1930, this play would be adapted into a silent movie of the same name.

Similarly, The Merchant of Venice was adapted for stage as Dil Farosh by Mehdi Hassan ‘Ahsaan’ in 1900, a direct adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. While Shylock is transposed as an Indian moneylender, the playwright did not really stress the anti-Semitism much since there wasn’t an acceptable equivalent in the Indian context. Baburao Painter adapted the play for the silent screen as Savkari Pash or The Indian Shylock in 1925, which witnessed the debut of Shantaram Rajaram Vankudre, better known as V. Shantaram.

The Merchant of Venice had several other screen adaptations – Dil Farosh, based on Ahsaan’s play, released as a silent movie in 1927; Baburao Painter remade his silent film as a talkie in 1936; and in 1941, Radha Film Company of Kolkata released their version titled Zaalim Saudagar, directed by J.J. Madan, who had earlier directed an adaptation of The Taming of the Shrew, titled Hathili Dulhan (1932) starring Khurshid, Patience Cooper, Abbas and Mukhtar Begum.

Among the Bard’s comedies, The Comedy of Errors was a particular favourite of Indian film-makers. Identical twins and mistaken identities provided ample scope for laughter. In 1869, Bengali educationist and social reformer Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar translated the play into Bengali. Titled Bhranti Bhilas, the plot closely followed the original though the structure of the play was altered into a novel. Interestingly, Bhranti Bhilas was [re]adapted into a play in 1888. The first known screen adaptation of The Comedy of Errors was Bhool Bhulaiyan (or Hanste Rehna), made in 1933.

It was not only the Bard’s comedies and dramas that found favour with Indian audiences. The tragedies were equally successful. Hamlet first found its Indian moorings in a silent film called Khoon-e-Nahak (1928) or Murder Most Foul, produced by Excelsior Films, and directed by K.B. Athavale. Macbeth, Shakespeare’s tragic drama of greed and treachery, resonated on the silent screen in 1930 as Khooni Taj (the film also had a Marathi title: Raktacha Rajmuku).

In 1935, Sohrab Modi debuted as a director with Khoon ka Khoon, based on Ahsaan’s Urdu adaptation of Hamlet. The film introduced the beautiful Naseem Banu as Ophelia while her mother, Shamshad Bai, played Gertrude. The film, however, was no more than a recorded play, with the movie camera too being the audience. And perhaps because Sati Sone amalgamated elements of Rajput folklore, Khoon ka Khoon is considered the first true adaptation of a Shakespearean drama in Indian cinema. In fact, Sohrab Modi is credited as the man ‘who brought Shakespeare to the Indian screen’.

The 1930s were an interesting period in Hindi cinema; ‘silent’ films were giving way to talkies. Indian film-makers were finding the Bard fertile ground for their screen adaptations. In 1935, Fram Sethna directed Khudadad, which found its inspiration in Jahangir Pestonjee Khambatta’s 1898 play of the same name. Starring Patience Cooper and Master Mohan, Khudadad was an adaptation of Pericles.

Possibly, the first screen adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s historical plays in India was Sohrab Modi’s Said-e-Havas (1936), based on King John. Meanwhile, Antony and Cleopatra was filmed in 1936 as Taj Pictures’ Zan Mureed or Kafir-e-Ishq; it was a screen adaptation of The Parsi Theatre’s Kali Nagin (1906), which had been adapted by Anwaruddin Makhlis and directed by Joseph David.

Moving into the 1940s and later, Shakespeare made only sporadic appearances on the Indian screen. In 1948, Nargis Art Concern brought out their ambitious adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. Starring Sapru and Nargis as the doomed lovers, the film kept characters and settings as close to the original play as possible. Similarly, Bina Rai essayed the eponymous role in director Raja Nawathe’s Cleopatra (1950), inspired by Cecile B Mille’s Cleopatra (1934). A dashing Ajit played Antony.

image courtesy: Filmfare, December 11, 1964

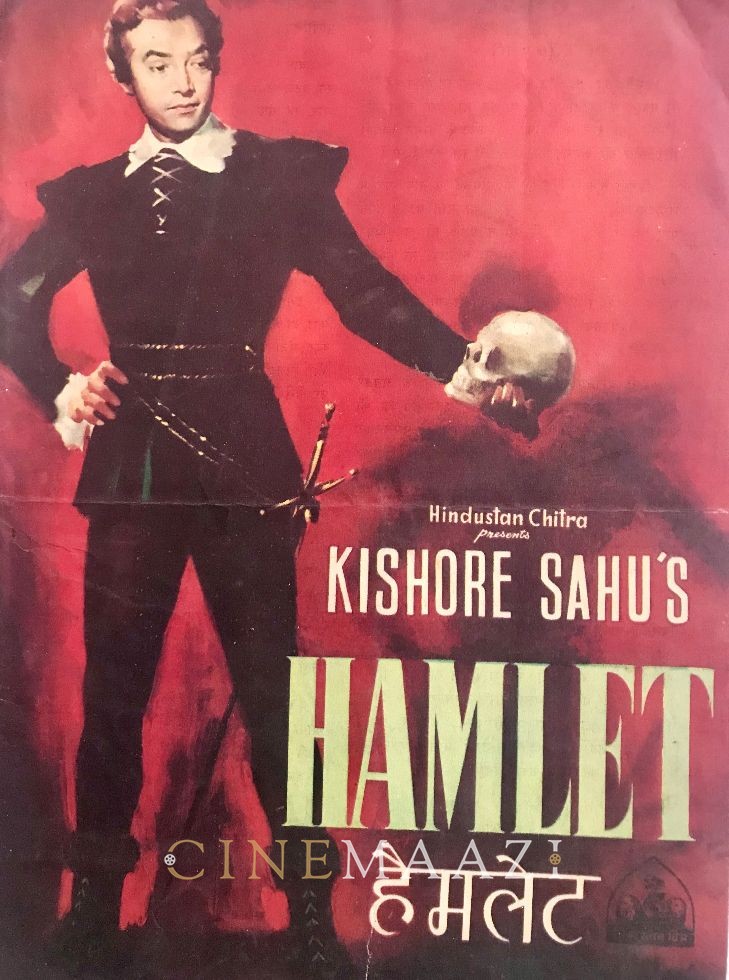

The tragic tale of the Prince of Denmark was re-visualized in Kishore Sahu’s Hamlet (1954). Though credited as a ‘free adaptation’, Sahu’s film stayed true to its source material, keeping setting and characters the same as the original. Priding himself on his ‘European’ sensibilities, Sahu took inspiration from Sir Laurence Olivier’s definitive Hamlet (1948). The film, which saw the then-two-film-old Mala Sinha take on the challenging role of Ophelia, incorporated not only dialogues from Ahsaan’s Khoon-e-Nahak, but also couplets from famous Urdu poets, including Bahadur Shah Zafar’s ‘Na kisi ki aankh ka noor hoon’.

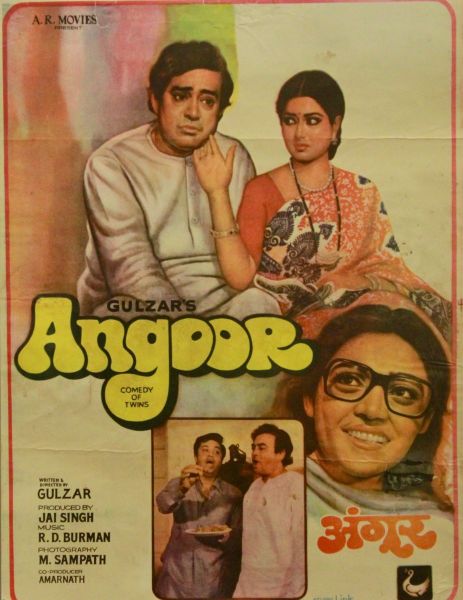

The Comedy of Errors shows up again, of course, this time in the zany Do Dooni Char (1968), starring Kishore Kumar and Asit Sen as the twin pairs of master and servant. Produced by Bimal Roy and directed by Debu Sen, the film was a remake of the 1963 Bengali film Bhranti Bhilas (starring Uttam Kumar and Bhanu Bandyopadhyay), which, in turn, was based on Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s work. The very next year saw a gender-reversed version titled Gustakhi Maaf (1969). Starring Tanuja in a double role, the film very loosely followed the plot of the original play, the major difference being that there was only one pair of twins. Then, Gulzar, who wrote Do Dooni Char for his mentor, Bimal Roy, adapted The Comedy of Errors as Angoor (1982) – one of Hindi cinema’s finest comedies. Gulzar even offered a nod to his film’s provenance: Angoor ends with Shakespeare winking at the audience from a lithograph on the wall.

Romeo and Juliet has also been a very popular source for modern adaptations. The play appeared in Mansoor Khan’s directorial debut, Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (1988), where the doomed romance played out in a setting of feuding Rajput clans. Habib Faisal reimagined the star-crossed lovers as scions of rival political families in his second film, Izhaqzaade (2012). The film took on issues of gender politics, societal hypocrisy, honour killings, inter-religious marriage, etc., and was a more contemporized adaptation of the tragic romance. Like Faisal, Manish Tiwary too set his adaptation Issaq (2013) in the hinterlands of India. Perhaps the most opulent and stylized version of the play was Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s version – in Goliyon ki Rasleela: Ram Leela (2013), Bhansali placed the doomed lovers against a backdrop of feuding Gujarati clans.

Encouraged by the critical response to Maqbool, Bhardwaj embarked on a retelling of Othello in 2006. Omkara did not aim to be ‘authentic to Shakespeare’ in its setting or characterization. Joyfully merging the gangster genre and politics in the Hindi heartland, Omkara was a more linear adaptation than Maqbool, though the latter was more faithful to Shakespeare’s lines. But the language used in Omkara was perfect – not the dramatic Urdu that earlier playwrights used to declaim Shakespeare’s monologues, but the lived-in local dialect redolent of the land where it was set.

In Haider (2014), the last of Bhardwaj’s trilogy of Shakespeare’s tragedies, the director opted to merge Basharat Peer’s contemporary novel, Curfewed Night, with the ‘rotten state of Denmark’. Audaciously, Bhardwaj pictured Gertrude/Ghazala as strife-torn Kashmir, torn between her husband (India) and his brother (Pakistan). While Hamlet himself became a politically aware poet who returns to find his homeland in the grips of armed insurgency.

Other lesser-known screen adaptations include 10ml LOVE (2010), a contemporary riff on A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Bornila Chatterjee’s The Hungry (2017), a pared-down modern take on Titus Andronicus, often described as ‘Shakespeare’s bloodiest play’. Neither film set the box-office on fire.

It is not only through adaptations and inspirations that Shakespeare has made his presence felt in Hindi films. Humraaz (1967), for instance, had a long enactment of a scene from Othello, while Karz (1980) borrowed the ‘play within a play’ trope of Hamlet for its denouement. Sundry other Hindi films were as inspired by Romeo and Juliet as they were by native tales of doomed love. Moreover, regional language films had their own adaptations, inspirations and indigenized Shakespeares while Indian films in English like 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981) and The Last Lear (2007) had a strong Shakespearean presence: if it’s an Anglo-Indian English teacher who teaches Shakespeare, offering a glimpse of Twelfth Night and direct quotations from King Lear in 36 Chowringhee Lane, The Last Lear is about a Shakespearean actor who is obsessed with Shakespeare, especially King Lear.

It just shows that Shakespeare isn’t going anywhere soon. As long as there’s an audience for audio-visual entertainment, there will always be a demand for the Bard of Avon. For, as Ben Johnson wrote: ‘He was not of an age, but for all time.’

Tags

About the Author

Anuradha C was a journalist with the Sunday Observer in Bombay. Now she writes, edits and is a media consultant for The Information Company. Her peripatetic childhood allows her to speak, read and write multiple languages. Anuradha blogs about movies, music and books at Conversations over Chai, and sub-titles old Hindi movies in her spare time.

.jpg)