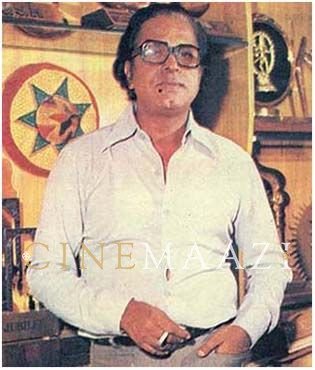

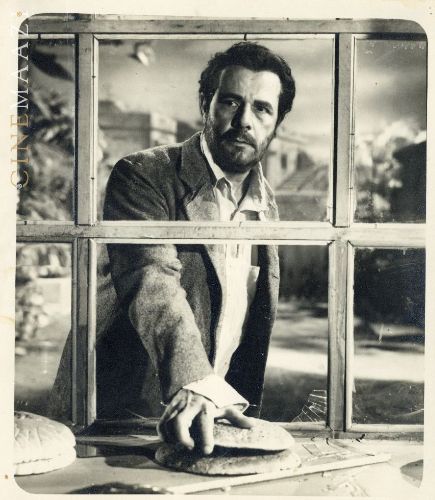

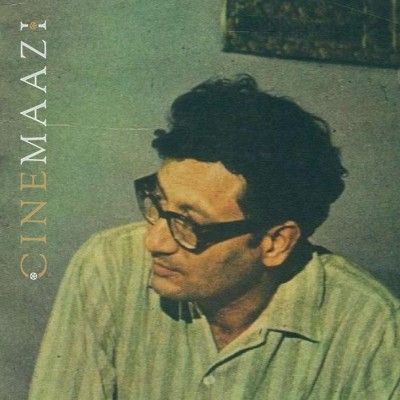

Sohrab Modi

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 2 November 1897 (Bombay)

- Died: 28 January 1984 (Mumbai)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Spouse: Mehtab

- Children: Ismail, Mehelli

Sohrab Modi was one of the early auteur-pioneers of Indian film making, whose presence dominated the early Indian talkies scene in a successful career in the various roles of producer, director and actor. Born on 2nd November 1879, he was the eleventh child in his family. On completing his matriculation, Sohrab Modi’s principal in school advised him to harness his sonorous voice and become either a politician or an actor. His interest in films piqued, he soon started a travelling cinema with his brother’s projector. He also took over his brother’s travelling theatre group and performed all over the nation.

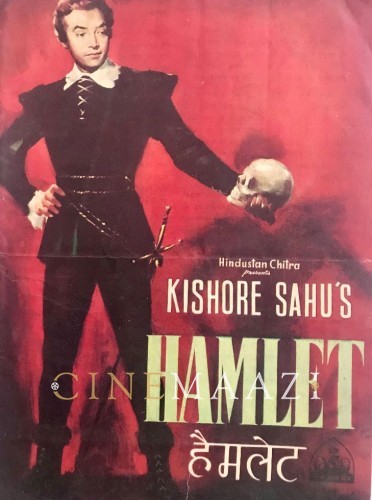

An actor trained in the Parsi Theatre tradition, he often performed Shakespearean plays translated into Urdu. Recognizing the decline in the popularity of theatre with the rise of sound films, he started the Stage Film Company in 1935. His first venture into film-making was a direct adaptation of one of his popular plays, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, titled Khoon Ka Khoon (1935). In the next year, he established the Minerva Film Company in Bombay. However, the first production under this banner, Saeed-E-Hawas (1936), an adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Life and Death of King John, as well as the two following efforts failed to be successful. For Saeed-E-Hawas, he set up two cameras to capture the performance, which was then edited into the final product. These initial attempts taught him the difference between stage and screen and informed him of the wide potential for the performing arts unleashed by the camera. For him, the mark of a director’s skill lay in their ability to translate a script onto the screen both visually and aurally.

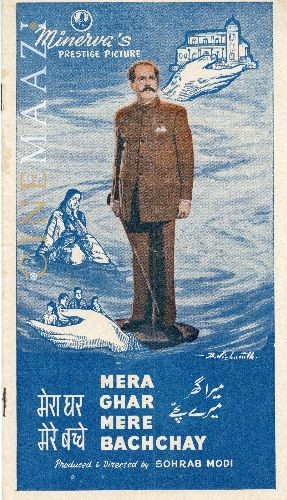

Sohrab then launched his own film production company Minerva Movietone in 1936, which would come to be known across the globe for big-budget historical dramas that rivalled its contemporaries in Hollywood in both scale and technique. The first few Minerva Movietone Productions, Jailor (1938), Talaq (1938), Meetha Zahar (1938) and Bharosa (1940) were social melodramas that tackled issues of infidelity, divorce, alcoholism and incest. Through the exposition of the film’s principal characters, Sohrab Modi addressed these problems from a viewpoint that was surprisingly progressive for its time. Woven into these social melodramas appears a vision of an India preparing itself for its impending independence, confronting out-dated value systems as it contended with a rapidly modernizing world. His formal approach as an actor seldom deviated from his theatre days. His co-star and wife Mehtab admitted that his commanding voice intimidated her terribly on set. Understandably, his impeccable delivery of Urdu dialogues and theatre-informed style memorialized him in the minds of the masses.

Sohrab’s prowess as a film-maker undoubtedly shone through in the historical genre. While he despised history lessons as a child, he valued historical narratives as a way to not only learn about the past but more importantly, learn from it to shape a better future. The period-piece trilogy of Pukar (1939), Sikandar (1941) and Prithvi Vallabh (1943) was a huge success. Pukar features beautifully written and philosophically charged monologues debating the idea of justice. The contradictions inherent in the Emperor’s commitment to a rigid ‘life-for-life’ juridical perspective ironically threaten the Emperor’s own life and marriage in the elegantly conceived film. At a time when the independence struggle was beginning to come into its own, this intelligent depiction of an indigenously conceived system of justice that could be perfected through reform struck a chord with many.

The epic Sikander (1941) on the other hand featured majestic sets and magnificent battles shot in the open fields of Kolhapur with thousands of extras and elephants. In the backdrop of World War II and the Civil Disobedience movement in India, it evoked historical grandeur on an unparalleled scale and a sense of national pride in every spectator. Though it gained censor approval, it was banned from theatres in army cantonments.

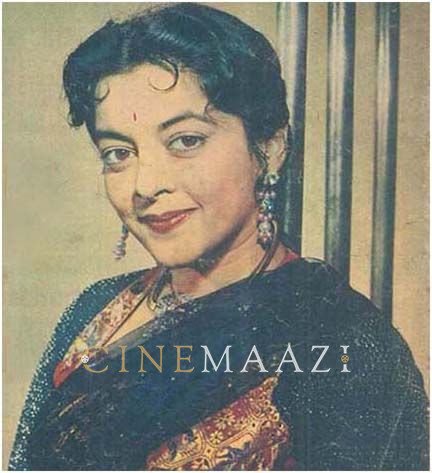

He met the actress Mehtab while directing Parakh (1944) for Central Films. He subsequently cast her in Minerva Movietone's Ek Din Ka Sultan (1945). Sohrab Modi proposed marriage to Mehtab despite opposition from his Parsi family. Mehtab’s condition for marriage was the acceptance of Ismail, her son from a previous marriage. Sohrab began a family with Mehtab and her son, and they gave birth to another son, Mehelli. At present, Mehelli runs a UK-based art-house DVD company specialising in the re-mastering and release of rare arthouse and award winning films.

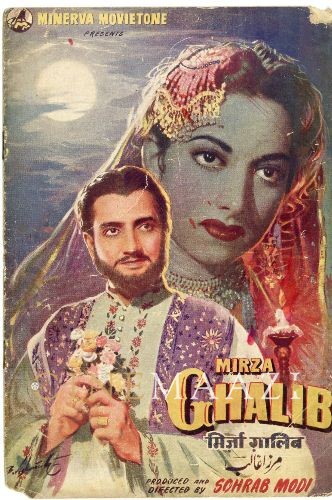

In 1942, Sohrab Modi began working on his dream: his self-proclaimed magnum opus Jhansi Ki Rani starring Mehtab. The first Indian film shot in Technicolor by a diverse international crew, the film was finally realized in 1953 after spending an amount almost equivalent to one crore rupees at the time! It accrued critical praise, but its monstrous budget meant that the film failed commercially. However, he bounced back spectacularly the following year with Mirza Ghalib (1954), which won the actress Suraiya praise from Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru himself. It is the only instance of a movie being awarded both the President’s Gold Medal for All India Best Feature Film as well as the President’s Silver Medal for Best Feature Film in Hindi.

Sohrab’s final directorial venture came with Meena Kumari Ki Amar Kahani (1979). A splendid 48-year film career came to an end with Kamal Amrohi’s Razia Sultan in 1983 where he lived out his dream of playing the Prime Minister in the role of the eponymous queen’s Vazir-e-Azam. Sohrab received the prestigious Dadasaheb Phalke award in 1980. His Phalke medallion caused quite a stir when it was found in 2005 in Mumbai’s infamous antiques market Chor Bazaar, reportedly sold to a vendor by his son Mehelli. Sohrab lost large sums of money to opportunists who took advantage of his passion for film-making and ailing condition. Even when severely ill, Sohrab held a ‘muhurat’ for a film Guru-Dakshina in 1982 that never saw the light of the day. He lost his life to cancer a few years later at the age of 86 on 28th January 1984.

-

Filmography (28)

SortRole

-

Samay Bada Balwaan 1969

-

Jailor 1958

-

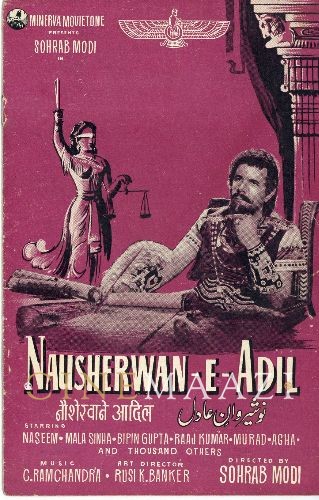

Nausherwan-E-Adil 1957

-

Rajhath 1956

-

Raaj Hath 1956

-

Kundan 1955

-

Mirza Ghalib 1954

-

Jhansi Ki Rani 1953

-

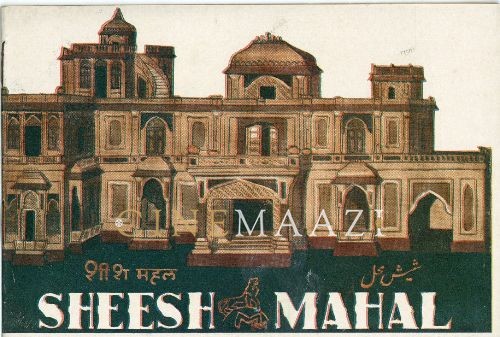

Sheesh Mahal 1950

-

Dawlat 1949

.jpg)