Lalita Lajmi on Guru Dutt: Unfinished Symphony

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

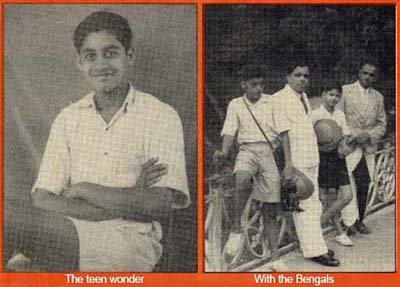

We lived in a tiny two-bedroom flat in Calcutta. It was crowded with my parents, nani and five of us children. We would keep colliding into one another. On hot summer evenings, my brothers, Guru Dutt and Atma Ram, would walk down to the Podopukhur tank for a swim. I would toddle behind them with or servant Nondo. We would sit on the lawn and watch my brothers. We’d be back home before dark. Nani would be lighting the diyas for her evening aarti. Guru Dutt must have been about 14 then; in the flickering light of the lamps, he’d make shadow figures of a swan or a deer. I’d watch, almost hypnotised, but he’d shoo me off.

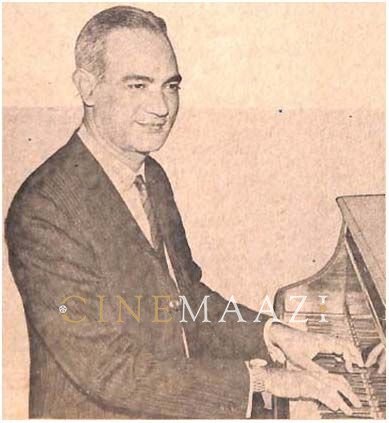

Every year nani would take us to the local Poush mela. Guru Dutt was fascinated by the clay toys and dolls. Even then he had an artist’s eye. An artist myself, l’ve always been struck by the play of light and shadow in Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam and Kaagaz Ke Phool. Guru Dutt dabbled with painting; there was an unfinished watercolour-a landscape painted when he was at the Almora Dance Centre.

Perhaps it was his love for the arts which made him so supportive of my work. Atma and he often gave me books on art. When I had my first exhibition in 1961, Guru Dutt bought two paintings though he never turned up for the opening. I was very hurt.

Guru Dutt was a very private person but he wasn’t a loner. He was particularly close to a Gujarati family. Naveen and Ratilal were a little older than him but they were always together. Atma tried to wangle his way into their close-knit group but Guru Dutt would always push him away. I didn’t even try. I was seven years younger than Guru Dutt and quite happy to observe him from the sidelines.

Atma was closer to my age; we always found something to quarrel about. Atma would chase me through the house, trying to pull my pigtails. Like a responsible big brother, Guru Dutt would come between us and play peace-maker. He always took my side.

We’re Saraswat Brahmins and devotees of Shanta Durga. Durga Puja in Calcutta is a time to celebrate…we did. Part of the rituals included sacrificing a goat to the goddess on maha ashthami. Guru Dutt hated the bali ceremony. He loved birds and animals. We had a pet parrot; Guru Dutt would sit patiently with it every morning, repeating words hoping that the parrot would learn to talk. It did… after many frustrating months.

Guru Dutt was deeply interested in dance. Once when Guru Dutt was very young my mother went for one of Uday Shankar’s stage shows and didn’t take him along. He was very upset. When he was 13, he went for a performance alone and was so impressed that he came home and told mother, “one day I want to be a dancer like him.”

At one gathering of the Saraswat community, Guru Dutt presented a surprise item. It was a dance... The Snake Charmer. Everyone was amazed by the genius of this 15-year-old. My uncle, B.B. Benegal, shot the performance on an 8 mm camera. Unfortunately the film is untraceable.

My uncle was an avid cameraman, he’d keep clicking. Guru Dutt, Atma and I would often find ourselves in the frame. He let Guru Dutt handle his camera once and was so impressed with some of the photographs my brother took, that he bought him his first camera.

His love for music and dance flourished during his years with Uday Shankar’s ballet troupe. In 1942, Guru Dutt was to perform at the Excelsior theatre in Bombay. We had moved to the city a day before the Quit India Movement was launched.

My brother got us passes for the show. We were wildly excited. Guru Dutt and Sundari Shreedharani performed the Swan dance which he had composed. Uday Shankar’s partner had returned to Paris, funds had stopped coming from abroad. This was one of their last performances. When we went backstage, Uday Shankar told my mother, “Your son is very talented. Even after our troupe disbands you must make sure that he continues dancing.”

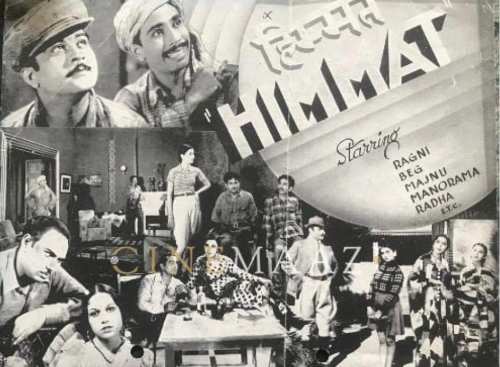

But dance appeared to have no future in the country then. In desperation, Guru Dutt wrote to my uncle, Benegal who was the publicist for all the theatres in Calcutta. It was thanks to him that Guru Dutt was taken on by Prabhat Films. He moved to Pune and worked as an assistant dance director…he also did bit roles in Prabhat’s early films like Lakha Rani.

Four years later, he was back in Bombay …without work. It was during this period that he wrote the first draft of Pyaasa. I guess, to an extent Pyaasa was inspired by my father. Father’s lifelong ambition was to edit a journal which is why he left his job as a headmaster in a Bangalore school… and moved to Calcutta. But there weren’t too many openings in the city of learning, so father was forced to accept a clerical post.

Guru Dutt inherited my father’s temperament. He was very quiet and a voracious reader. He knew Urdu, Hindi, English, Bengali and Konkani very well and always had a book in his hand. When he was home form Prabhat without work, he wrote many short stories which he would mail to The Illustrated Weekly of India which was then being edited by an Englishman, C.R. Mandy. Within a week, they’d be returned with a rejection slip.

I’m sure Guru Dutt would have liked to go to college. In Pyaasa there are shots of college life which have an air of sad nostalgia. But he sacrificed his dreams for the family. After his matriculation (our mother also appeared for the exams the same year), he gave up studies to keep the kitchen fires burning. His first job was as a telephone operator. With his first salary he bought saris for mother and nani, a dress for me, a Bhagwad Gita for his teacher and small gifts for everyone in the family.

Only Guru Dutt could conceive a film about a prostitute. He always had a compassion for “fallen” women. When he was in Pune, he was involved with a girl of dubious reputation. They almost got married but then he broke off with her. Perhaps she was the inspiration behind Gulabo’s finely-etched character.

In Aar Paar, he paid tribute to his first crush-a Sikh girl, the daughter of a garage owner in Calcutta. He was infatuated by her when he was 14. The girl would often visit us, everytime when she was about to leave she’d drop her handkerchief. Guru Dutt incorporated that bit in Aar Paar.

In Pyaasa, the poet’s brothers plot and scheme against him, leading critics to speculate if they were a throwback to his unhappy childhood days. Not at all! We were all very close. But some of the family elders strongly disapproved of his profession. Because Guru Dutt had joined the film industry, he was scorned and ridiculed. He never forgot the insults.

One of our maternal uncles was the managing director of a mill. He was one of our few wealthy relatives. Guru Dutt knew that he was well-acquainted with some film financiers and distributors. My brother needed a job desperately then, he went to see my uncle in his flat on Malabar Hill. My mother warned him that he would not be welcomed but. Guru Dutt was optimistic. Uncle had two sons-one was Atma’s age and one mine-and had lost them both within a month of each other to typhoid and meningitis. Guru Dutt perhaps hoped that uncle would treat him like his own son. There was a distributor with uncle that day but he didn’t introduce him to Guru Dutt. In fact, he pretended that my brother didn’t exist. Years later, when Guru Dutt was a successful film-maker, the same uncle would come and stay at our house. But Guru Dutt never spoke to him.

He didn’t want to act in Pyaasa. In fact, he would have been quite happy to stay behind the camera. He’d been forced to turn ‘hero’ in Baaz because his friend Dev Anand was a big star then and he couldn’t afford to pay his price. But for Pyaasa he signed Dilip Kumar and spent the first day on the sets waiting for the star to turn up. He didn’t. Dilip Kumar was shooting for Devdas at the time, he felt that the character of Vijay was too similar to Devdas. He didn’t want to repeat himself. He dropped out and my brother stepped in. Today it is hard to imagine anyone else as Vijay.

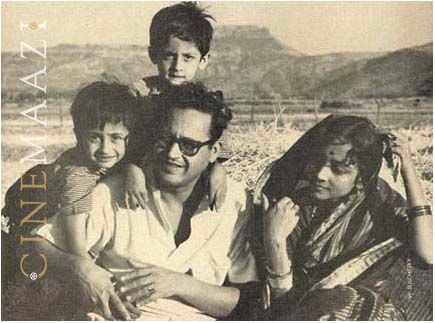

Though Pyaasa is his most talked-about film, Baazi was the beginning. One evening, he returned home laden with gifts and the news that he was directing a film. We attended the first song recording. Geeta Roy was at the mike singing. Taqdeer se bigdi hui tadbeer bana le. It is commonly believed that this was the first time Guru Dutt met her… but once he confided to me that he had been earlier introduced to her by Dev Anand at a party.

Geeta was a very good looking girl with the most beautiful eyes l’ve ever seen. My brother had a soft spot for Bengali songs my aunt would play on her gramophone. He would listen to one of Geeta’s songs over and over again, Tumi Jodi bolo bhalobasha dete Janina… He was in love.

Geeta would often drop in at our Matunga apartment. She was a top playback singer but she had no airs. She would come straight into the kitchen and start chopping vegetables. She used to call my mother mashima (aunt) till the end. She wanted me to call her didi and speak to her in Bengali. I called her Geeta and spoke to her in Hindi.

One night, I was walking her home when Guru Dutt slipped a letter to me for her. All through their courtship days, I was their courier and chaperone.

Her family didn’t care much for Guru Dutt. He belonged to a different community and he was only a struggler. They preferred the Bengali boy she was engaged to. But Geeta was drawn towards him. Often her brothers would come home looking for her. If they found her, she’d say she’d come to meet lalli… me. She was recording round the clock then but if she ever got a day off, she’d drive down in her car. Guru Dutt, Raj Khosla and I would pile in and we’d go for a long drive usually to the wonderfully secluded Powai Lake. Raj and I made sure the couple in love had some time together.

Steadily Guru Dutt achieved success. During his struggling days he’d spend hours scribbling Guru Dutt on pieces of papers. That was how he signed autograph books but for banking purposes and other legal formalities he signed his full name, Guru Dutt Padukone. We bought ourselves luxuries we’d only dreamt about. Our first fan… the radio on which we heard about Gandhiji’s assassination. For years we kept that radio as a memento. Guru Dutt soon had a fabulous wardrobe. There was a time when he couldn’t attend a shooting schedule because he had only two pairs of trousers: one was dirty and the other was at the laundry.

Guru Dutt had seen the Bengali original of Sahib Bibi Aur Gulam with Uttam Kumar playing Bhootnath. He read the novel 22 times to absorb the character.

When I first saw Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam it had a different ending. Meena Kumari is sitting beside Guru Dutt in the tonga, her head on his lap. After a while she tells him softly, “Bhootnath, you should get married.” Before he can tell her that he has married Joba, some highway bandits stop the tonga and kill her. Distributors objected to this ending because they felt that audiences would assume that Bhootnath and the chhoti bahu were lovers. That wasn’t Guru Dutt’s intention. Bhootnath looked up to her the way Guru Dutt idolised his own aunt Vimla Benegal.

We also saw many versions of Kaagaz Ke Phool. Guru Dutt actually wanted Ashok Kumar to play the role of the ageing director but eventually he did the role himself.

On the night of the film’s premiere in Bombay, Guru Dutt was high. He’d had a bit too much to drink. He knew the film would flop. It was evident from the audience’s reaction at the Delhi premiere. The President, Dr. Radhakrishna, was the chief guest. He was so shocked to see the crowds booing and throwing things at the screen that he walked out. After that Guru Dutt’s name never appeared in the credit titles as director.

Critics insist that he modelled the character of Veena in the film after Geeta. But Geeta was not against the film industry. She never wanted him to quit. In fact, Guru Dutt and she would often sit together in the evenings and discuss the music of his latest film.

My mother didn’t want any woman to get close to Guru Dutt. I guess my mother was very possessive about her favourite child. There was a tussle for his affections even with Geeta. Despite this, my mother was very fond of Geeta. Like most Bengalis, Geeta was very warm and respectful to elders.

My brother loved her to the end. Knowing that Geeta wanted to act, he intended to produce and direct a film for her. Gauri was about a sculptor, Geeta was playing the title role. Some songs were recorded, some reels shot when Geeta had some ego problems and backed out. The film was shelved.

Geeta loved him passionately but she could never trust him. She refused to let Guru Dutt work with Nargis, Meena Kumari and other top heroines. She had a circle of friends who egged her on, to an extent they were responsible for distancing her from my brother. When she complained of insomnia, they prescribed sleeping pills which soon became a habit for both of them. When she confided that she was feeling low, they offered her whisky. Alcohol which started out as a “fun thing” soon became an addiction. Even Guru Dutt was finding more and more comfort in the bottle. But he never drank on the sets…he’d drink only during the long and lonely evenings.

Geeta could be moody. Even before they were married, after one of her arguments with my brother she had disappeared for days. She went off to a friend’s place in Bhusawal without telling anyone. Guru Dutt was worried out of his mind. After marriage, she’d go away to her maike with their three kids.

She maintained that their Pali Hill bungalow was haunted…that a ghost who lived on a particular tree was destroying their marriage. She also had a thing about a lovely statue of Buddha which was kept on the sideboard in the drawing room. She insisted it was unlucky. After Guru Dutt died, I brought home the Buddha, a dragon statue he’d picked up from Nepal and his favourite ashtray. They’re still with me.

Geeta insisted that the bungalow on Pali Hill should be razed. Guru Dutt agreed though it broke his heart. He moved to a small flat in Peddar Road and she shifted with the kids to Santa Cruz. They had been living separately for a year when he died.

Geeta wouldn’t agree to a divorce, neither would she allow him to meet the kids too often. The evening before he died, he had called up Geeta from the neighbour’s since he didn’t have a phone. He asked her to send the kids over. His shooting in madras had been cancelled, he was home alone. She refused. He was feeling very low…after working on the script for a while, he told Abrar Alvi, “I don’t feel like eating. I think I’ll retire for the night.” He shut the door… the next morning it had to be broken open. Guru Dutt was no more.

There was an open novel by his side and a glass with some pink liquid. His hand was outstretched, his eyes open, it seemed as if he was trying to get up…say something. My cousin, who was a doctor, said that death must have come sometime between 4 a.m. and 4.30 a.m. his body was discovered around 9 a.m. when I reached the house around noon, my mother, my husband and Geeta were already there. Geeta looked at me and said softly, “You will all blame me for his death, won’t you?”

I don’t blame her. I blame myself. Guru Dutt had attempted suicide on at least three other occasions. Twice he’d taken an overdose of sleeping pills and once he had swallowed opium. He was in Pali Hill then, when we rushed across we found that his body had turned cold and his vision was blurring. He kept repeating, “I’m becoming blind, I can’t see.” We saved him.

A few months later, he again emptied a bottle of sleeping pills and had to be rushed to Nanavati Hospital for a stomach wash. He was in a coma for three days and nights. He kept asking for Geeta.

That suicide attempt had been deliberate, pre-planned. He’d even written a letter for Atma, asking him to look after Guru Dutt Films, Geeta and the kids. I wish we’d taken him to a psychiatrist then. We did call a shrink once but he charged Rs 500 for a visit and Atma laughed that he was very expensive. We never called him again.

I’ve been told that if you have a lot to drink and then take sleeping pills, it can induce a heart attack. His valet told us later that he’d been complaining of chest pain the previous evening.

The last shot he gave was with Mala Sinha. And it was prophetic. He hands over his resignation letter to Mala Sinha who was playing his boss in Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi and says, “I’m leaving.”

After his death Atma found it very difficult to complete the film. In the industry it’s a bad omen to step into an unfinished film. Finally, it was directed by Shahid Lateef and completed by Atma with Dharmendra stepping into Guru Dutt’s shoes after several other actors had turned Atma away. The film was a wash-out.

So was Khule-Aam, the film his sons made. It again starred Dharmendra and took six years to complete. The time lapses were evident, the film looked disjointed. Tarun and Arjun lost a lot of money and the debts that piled up literally killed Arjun. He had stayed over at our place the previous night…by the next evening he was dead.

Tarun shared his birthday with his father-July 9. (Arun was born a day later). He also had suicidal tendencies, like Guru Dutt he’d consulted a psychiatrist only once.

Today even Atma is gone and Guru Dutt Films has been sold. All that remains of my brothers are a lifetime of memories…and a lot of respect.

In October last year, there was a three-day festival of Guru Dutt’s films at Birmingham organised by Parvez Khan.

His films were screened in London too at the prestigious National theatre…at the Museum of images. The event was organised by the British Film institute, Gopal Gandhi, the director of the Indian High Commission, and Nasreen Munni Kabir. I was invited to speak about my brother before each show and I was amazed by the respect people still have for him.

They weren’t only film buffs and Indians but students of serious cinema and Englishmen who had tears in their eyes after the screenings of Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam and Pyaasa.

One young man wanted to touch my feet when he heard that I was the sister of the man who had directed Pyaasa. It made me feel that my brother was still alive…his death was a mistake.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's February 1995 edition as told to Roshmila Mukherjee by Lalita Lajmi (Guru Dutt's sister)

The images are taken from the same article.

.jpg)