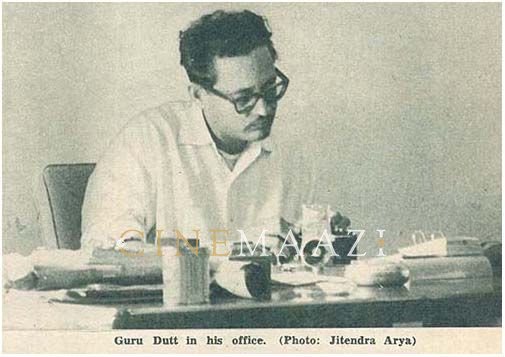

Hamlet of Films - Guru Dutt

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

"He was the greatest introvert that I have ever known...

I wish he had talked more, then perhaps he would still alive..."

People agreed they had never seen a handsomer corpse...

There he lay on the bed - sprawled on his back, face relaxed in a serene repose. What baffled everyone, was the right-hand fore-finger gently resting on his chin - as if he was lost in deep thought. He just couldn't be dead - he would wake up any moment from his reverie. It was hard to believe that Guru Dutt was really no more.

The man who had been a thinker all his life-kept on thinking even in eternal sleep, his brain was the most dynamic part of his being and the last part to surrender life to the Eternal.

He used to say- "It is not difficult to make successful films which cater to the box-office alone. The difficulty arises when purposeful films have to be shaped to succeed.at the box office." That was Guru Dutt. His restless, creative mind first created problems, then set about solving them.

There were occasions of depression. When funds ran out; he would decide to make a box office film in order to replenish his stock and continue the battle. But the more he matured as a filmmaker, the more restless he became after making such a decision.

Nobody could ever have cared less for money. I have seen him squandering lakhs- not for personal indulgence but for his art. So many artistes were signed and paid but never utilised, so many stories were bought which never went on the floors, so many films which went on the floors were never finished.

If with the cancellation of a film in the making, some people who had got a break in that film, found their hopes ending - Guru Dutt's heart bled for them. For days I have seen him sulky and morose, not because his money went down the drain, but because he felt he had let down these people. He did not even have the heart to face them and people misunderstood. If only people could have understood his innate sincerity to his art...

Ruthless Honesty

I remember the evening when Guru Dutt, actor Ram Singh and I were at Guru Dutt's cottage in Lonavla. Guru Dutt had just announced his decision not to direct "Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam" (1962) himself and had asked me to shoulder that responsibility. Ram Singh tried to reason with him. The story was not an easy subject for a beginner to handle. I seconded Ram Singh. Guru Dutt replied, "The trouble is, Ram Singh, that not only do I know how to direct, I also know what it takes to direct. The mental agony, the emotional fatigue that I am going through is hardly the condition even for a master to be in while directing. I don't care what people say. All want is that the job should be done as efficiently as possible under the circumstances." Only a man who was basically, incorrigibly honest to his art, could have said that.

And that must have been true. Recollecting the twelve years of our association, I cannot recall a single instance when the man told a lie. And believe me; I am not lying when I say that. He always took honesty a bit too literally. Before the release of "Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam" (1962), the censors objected to a shot in the picture. I felt the shot was vitally needed so in the editing room, I scissored it to the minimum. In walked Guru Dutt and demanded why I had retained even that much of the shot. I explained the major portion had been cut to please the censors - the rest would go unnoticed. He asked, "Would you want to cheat the censors?" I protested: "But it is for the picture's good." "Cheating is never good Better cut out the shot in toto." I had to

I wish he had not been given to so much brooding. The quality which proved an asset in his profession, proved a torture in his private life. He was the greatest introvert that I have ever known - a very very lonely man. I wish he had talked more, I wish he had not worn a perpetual pensiveness on his brow, I wish he had laughed more... then perhaps he would still be alive. At times, he would come to me late in the night - I knew some thing was weighing on his mind which he wanted to share with someone. He would be struggling to come out of his shell and the surest way to throw him back into it was to ask him, "What's ailing you? Come on, get it off your chest." So I would bide my time talking of this and that, patiently waiting for him to come out with it on his own. So many times he would come to the verge of it but then would check himself. He would let himself be stifled by his own woes - rare were the occasions when he would share them.

It was nearly midnight on the 18th of September when he walked into my house. I could sense that he was emotionally upset. By the time he left, it was five in the morning. Still I did not know what was troubling him.

One evening after we had dined together, I retired to my room to write and later dozed off. Next morning I learnt that he had dashed off to his studio at three in the morning when he could no longer bear to look at the oppressive walls of his room. That was the sort of life he had been leading for the past few months - alternating his nights between the lonely office (where he had installed a couch for sleeping) and the lonely bedroom of his flat, changing venues to appease his restless, tormented soul, trying to lose himself in voracious reading.

On the fateful night - 9th October - I went to his flat at about 8.30 p.m. - I had moved back to my home two days earlier. That night I had to read out the last scene of "Baharen Phir Bhi Aayengi" (1966) to him. It was the death scene of the heroine. I read the first part - he made some comments... second part... his comments.

I came to the third part - the heroine, deserted by her sister, by her colleagues, by everybody, shuts herself up in her sanctuary. She is in a mentally deranged state. The accent is on her loneliness.

I finish reading. No comments from him. I wait. He remains silent and brooding. Finally I ask, "Did you like it?" He does not reply directly - says, "You know, Abrar, I have a fear that someday I also may go mad. Loneliness could really be very oppressive."

Finally he listens to the complete scene. When the heroine dies the picture ends with recitation of a couplet:-

Baharen phir bhi aati hain, Baharen phir bhi aayengi

He said approvingly, "You know, our heroine is going to score in this picture."

And with that he closed his bedroom door. How little did I know then that he was going to retire forever.

He waited for me to finish my writing. As we moved to the dining table he said, ''You two have your dinner. I can't. I am feeling very tired. I would like to retire." And with that he closed his bedroom door.

How little did I know then that he was going to retire forever.

Next morning when the bedroom door was broken open, he was found in that serene but unusual posture of thoughtful, eternal sleep. In the short time and space at my disposal, I find it impossible to do justice to the personality that was Guru Dutt. There are others in films who are great. But he was so different, so unique with a stamp all his own.

It needed a Shakespeare to immortalise Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Would that Shakespeare had lived in this generation and known Guru Dutt, the Hamlet of films. He too would have been immortalised.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's 30 October 1964 edition written by Abrar Alvi.

The image is taken from the original article.

.jpg)