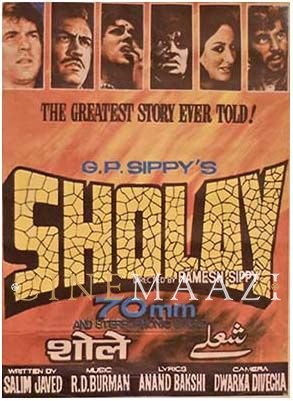

From Stereophonic Roar to Smartphone Whisper - 50 years of Sholay

14 Aug, 2025 | Short Features by Asha Batra

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

When Sholay hit the screens on 15 August 1975, it didn’t just play in theatres — it occupied them. A format so rare in India then that most cinema goers had never seen anything like it. Projected on a giant 70mm screen, the Chambal ravines stretched endlessly, the hustle and bustle of village and every close-up of Gabbar Singh felt larger than life. The format wasn’t just a technical choice — it was part of the storytelling, a canvas big enough to hold both the epic landscapes and the smallest flicker in an actor’s eyes..

And then was the stereophonic sound — a first for Indian cinema. It wasn’t just background music or dialogue but a living experience of the sound in film coming from not only left, right and center but from center left and center right of the cinema hall. Bullets didn’t just “sound” — they moved, whizzing from one end of the theatre to the other , horses thundered past your ears. Gabbar’s laugh didn’t come from the front speakers; it circled around the hall with menace, closing in on you.

The team, Ramesh Sippy, R D Burman, Salim-Javed, Dwarka Divecha, M S Shinde, knew they were building something for the big screen. They staged action in such a way that it could travel across that wide canvas, capture the moments of silence which were specially designed to make the sound bursts more startling, and the usage of stereo placement was like a conductor directing an orchestra.

An Immersive Experience

When Sholay was made the audience didn’t just watch Sholay — they entered it.

In the early 1970s, cine goers were mostly watching films entirely in monophonic sound, where every sound from a speeding car to a whisper came from the center speaker, flat and directionless. Sholay changed that forever. Presented in 70mm with stereophonic sound, it delivered sharper, richer visuals and a soundscape split into multiple channels — left, right, centre, and surrounds — allowing each element to be placed exactly where it belonged.

The opening credits set the visual and audio tone right from the first frame. As the steam engine slows to a halt, its chugging fills the theatre. The credits roll on, giving way to the vast ravines that stretch across the 70mm

R.D. Burman’s score sweeps in — guitar strumming from one side, a steady rhythm anchoring the center, harmonica curling through like wind over the cliffs. Around it, the creak of cart wheels and faint human calls pull you into Ramgarh before a single line is spoken. This isn’t just a credit roll — it’s the film’s first act of immersion.

Thereafter as the film moves, various Scenes like the train robbery, Gabbar’s first introduction, the temple prayer, and the last fight scene became an immersive events for the audience, not just sequences.

But technology was only part of its magic. Perfect casting, iconic performances, unforgettable dialogues, music, and Ramesh Sippy’s masterful direction fused into something unrepeatable. Fifty years later, Sholay still proves that some classics deserve to be experienced in their original format.

From 70mm to the Smallest Screen

Fast forward to today as we celebrate its 50 years of release, the same film often plays on a vertical screen no bigger than your hand. The shot of Jai and Veeru riding together on the motorbike, once framed against miles of open terrain, is now a cropped sliver of sky and dust. Gabbar’s menacing stance on the rocky outcrop loses the expanse beneath his feet. The iconic train sequence, designed to stretch from one end of the 70mm frame to the other, is now compressed into a narrow column, the sense of scale sacrificed for portability. This shift from 70mm grandeur to OTT convenience isn’t just about changing technology — it’s a transformation of the very way we experience stories. So what happens to Sholay when the silver screen becomes a smartphone?

Today, we can watch Sholay on our phones or on the little screens fixed on aircraft seats — and we do. But here’s the thing: Sholay wasn’t made for your palm. Shrinking it down to fit a vertical frame is like folding a painting in half to fit your wall. The story survives, the faces are still there, but the air around them, the sheer space the film was meant to breathe in — that’s gone.

As a cinephile, this isn’t just nostalgia talking. It’s about intent. A 70mm film is not just “big” — it’s built for bigness. The rhythm of shots, the timing of reveals, the way music swells into a panoramic view — these things only land fully when the format they were made for is respected. Watching Sholay on a small screen is not a crime, but it’s a different film in that moment. The bullets no longer travel across space. Gabbar’s laugh doesn’t surround you. Ramgarh doesn’t feel like a place you could walk into.

The Archivist’s Dilemma

As a cinema archivist, I feel this shift even more sharply. Our job is to preserve films as they were — not just the reels, but the experience. The 70mm prints, the original stereophonic sound mix, the projection notes — these are not museum pieces, they are keys to unlocking the film’s true self. And yet, I also know the modern viewer lives on digital platforms. If I keep Sholay locked away in its original form, untouched and unseen, it risks becoming irrelevant to those who’ve never experienced the magic of a cinema hall.

That’s the tightrope: to preserve and to adapt. Preservation means keeping the original intact for special screenings, for festivals, for those who seek the immersive truth of the work. Adaptation means bringing the film to OTT or even to vertical social formats — but doing so respectfully. No aggressive cropping. No “fitting” a panoramic shot into a square. No flattening of that glorious sound. And perhaps most importantly — letting the audience know what’s changed, so that the digital version becomes a doorway, not a replacement.

Why I Write This?

When Sholay played in its original glory, cinema wasn’t just content. It was an event. You didn’t scroll past it — you bought a ticket, stood in line, found your seat, and surrendered for three and a half hours. The sound didn’t come from a Bluetooth speaker; it came from around you, behind you, above you. The image didn’t compete with incoming notifications; it claimed your full field of vision.

Now, when I watch it on a streaming platform, I feel both gratitude and loss. Gratitude that the film lives on and can reach a generation who might never step into a 70mm hall. Loss because I know they will never feel that first shock when the stereophonic bullets whip past their ears, or when the train in the opening scene rumbles from one side of the theatre to the other, carrying with it the weight of a whole world about to unfold.

And maybe that’s why I write this — because as the formats keep changing, someone has to remember what it felt like to sit in that darkened hall in 1975, heart pounding, eyes wide, ears alive, watching not just a story, but a piece of history roar to life.

639 views

About the Author

.jpg)