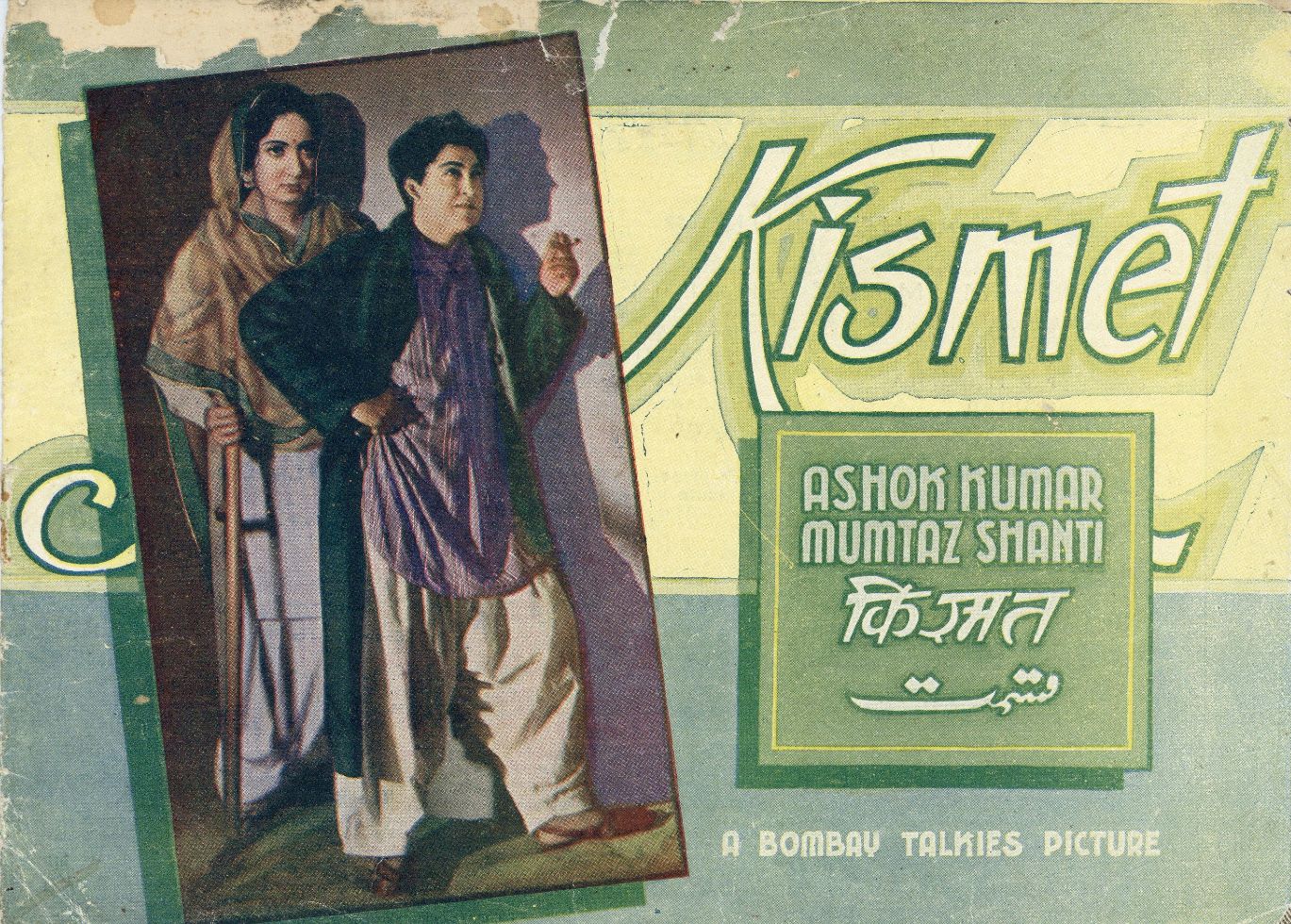

Title: Kismet (or Fate)

Director: Gyan Mukherjee

Year:1943

Length: 143 mins.

Starring: Ashok Kumar, Mumtaz Shanti, Shah Nawaz, P.F. Pithawala, Chandraprabha, V.H. Desai, Kanu Roy.

A film with the reputation of being the first big-hit ‘blockbuster’ of Hindi cinema, Kismet was made during a tumultuous time, both for the country and for Bombay Talkies. In the years following founder Himanshu Rai’s death, just about at the outbreak of the Second World War, the studio was in process of ceding control from Devika Rani to Sashadhar Mukherjee, subsequent to which it would produce successful hits, as well as later go into bankruptcy. The studio excelled in making the social drama or ‘socials’, with a melodic soundtrack, sentimental plot, and evocative dialogue. Agha Jani Kashmiri, who wrote the film, was trained under Himansu Rai, and the influence shows - the halting speech, coyness, and witticisms of the lead characters are distinctly reminiscent of Talkies’ earlier hits such as Achhut Kanya (Franz Osten, 1936). Noir-esque part-drama, part-comedy, Kismet doesn’t fashion itself blindly on the studio’s earlier successes depicting rural or suburban, pastoral lives, with a social message at the end. It keeps the legacy alive through elaborate sets, expressive lighting, and a family-centric plot. While Achhut Kanya bordered on tragedy, depicting social evil and the misfortune of being born as a low-caste in village society, Kismet is a considerably light-hearted, cosmopolitan dramedy that navigates through peculiarities of city-life, such as brokerage, debt, the business of entertainment, and petty crime. The oft-forgotten forties’ film-critic extraordinaire, Iqbal Masood, calls Kismet ‘India’s first genuine comedy’, ‘both funny and self-parodic’.

Shekhar (Ashok Kumar) is a petty thief, just out of jail. Irreverential to the law, the first thing he does after being released is to lift an expensive watch from a pickpocket to sell it to a pawnbroker. Turns out the watch belonged to an aged vagrant ( Pithawala) who was devastated at its loss, both because the watch was the last of his riches, all of which he had lost, and also because he had planned on pawning it to see his estranged daughter perform at the theatre. Shekhar, always in good-humour, decides to help the old man watch Rani (Mumtaz Shanti) perform. Rani, the man narrates, is now a cripple, but once her little feet would fill up the stage in the most beautiful, rhythmic dance. As a child, her father in a drunken fit of avarice danced her to exhaustion, after which she could no longer walk. Soon, the father lost his riches to the bottle, and abandoned Rani who, along with her sister Leela (Chandraprabha), was indebted to the now-owner of the theatre, Indrajit, who had once worked for her father. After the performance, Rani spots her father taking money from Shekhar, and tries to follow him, almost getting hit by a running car from which Shekhar saves her. She is immediately taken by his generosity, seemingly trusting him instinctively. Meanwhile, Shekhar slips in through a shadow and steals an expensive necklace worn by Indrajit’s wife to the theatre. On being pursued by the police, Shekhar hides the necklace in the carriage that Rani ends up hiring. He follows her home, and breaks in, but falls while climbing down the rickety staircase, spraining his ankle, and is seen by the police. On finding him inside the house, Rani is surprised, but thrilled. She tells the cops off for assuming he is a thief, offers him a change of clothes, tends to his leg, and asks him to spend the night. Over time, they fall in love, and he discovers that Rani is so deeply obligated to Indrajit to pay off the debts of her father that she has to resort to selling off objects of sentimental value, such as the ancestral piano, and also the very necklace he had stolen from Indrajit’s wife. As he had already pawned the necklace, he goes back to retrieve it, and gifts it to Rani as an indirect confession of love. He warns her not to wear to it the theatre lest anyone discover it. Unaware of the necklace being a stolen object, she wears it to the theatre anyway, where Indrajit’s wife spots it on the performer. The stern but paternalistic cop (Shah Nawaz) requests her to give the thief away, but she refuses, and Shekhar turns himself in to save her from the trouble. Coming to know of his truth, Rani is deeply hurt. However, earlier, Shekhar had met with a doctor who assured a cure for Rani’s paralysis, for which he required Rs 15000. Promising the commissioner this would be his last robbery, he hoodwinks the police yet again, and successfully robs Indrajit. Rani undergoes surgery, and Shekhar turns up at the hospital, where the police turn up. He narrowly escapes yet again, and everyone is increasingly frustrated at the rogue. It is also revealed that Indrajit had a son who ran away from home as a child and never came back, and the family is still heartbroken over the incident. Meanwhile, Indrajit’s son Mohan (Roy) gets Rani’s sister Leela pregnant, and Indrajit is entirely unwilling to let their union take place. The commissioner comes up with the idea that if Rani performs on stage for the first time after surgery, and dances, there is no way Shekhar would miss it. He is right, and as Rani dances beautifully to Ghar Ghar Me Diwali Hai,Mere Ghar Me Andhera, Shekhar is present, and is so overjoyed that he sheds his disguise. He is caught, but Rani reveals that she had performed strictly under three conditions, that charges against Shekhar be dropped, and that Indrajit agree to marry Mohan to Leela and waive off all of Rani’s father’s debts. In a twist of fate, or kismet, it turns out Shekhar is Indrajit’s long lost son, effectively making Shekhar, Rani, Indrajit, his wife, Leela, and Mohan, all part of the same, big, happy family.

Dheere Dheere Aa Re, Badal sung by Amir Bai Karnataki and Ashok Kumar, is particularly haunting, so is Papihaa Re Mere Piyaa Se Kahiyo Jaay by Parul Ghosh. The plot of the film is quite convoluted, and could certainly be read as an allegory for a number of things. The song Rani performs in the beginning, Hindustan Hamara Hai, is perhaps the first patriotic, nationalist song to be shown in a Hindi film. In the song, actors dressed as soldiers claim to be ready to defend the nation from all outsiders, German or Japanese, and this is the first of the few clear allusions to the political turmoil of the time. The sentiment could covertly be anti-British, but overtly the film had to support Axis powers. Certain film scholars are of the opinion that broken-legged Rani, with her trusting nature, her lost glory, and paralysis is allegorical of the nation itself - exploited and robbed off her riches to live helplessly in poverty, to be saved by a trustworthy thief.

The abrupt turnaround resolution of a fairly complex plot in Kismet could be symbolic of the aspiration of normalcy by the average Indian cinemagoer, or the purported audience, at a time of irrepressible political turmoil. Even though the themes in the film were dark and controversial - crime, debt, poverty, and pregnancy, the way they were treated left ample space for intervention by negotiation, reasoning, good-will, all eventually leading to resolution of conflict. Felony and law kept coming to terms with each other, but without the threat of imminent violence. It is certainly an optimistic film in its way - at a time when tomorrow was uncertain for a number of people in Bombay, further east, and in the rest of the country, it was necessary to show that the law can be merciful and nurturing. Though the film has been criticised mostly for normalising crime and showing it in a positive light, there is much to be said about the film’s three-year successful run in Bombay theatres, alluding to the ways in which audiences began to relate to complex and morally ambiguous characters.

Tags

About the Author

Ambuja Raj is pursuing an MPhil in Social Sciences from The Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, after having completed a Masters in Film Studies from Jadavpur University in 2018. For her Master's thesis, she engaged with the history of Indian Cinema, specifically the films of the studio Bombay Talkies. She is interested in the field of visual culture, as well as the history of popular culture in India. Her favourite Hindi film director is Saeed Mirza, and she has made a small film in tribute to him called Saeed Mirza ki Ajeeb Daastan.

.jpg)