The Colour of Strength: Soumitra Chatterjee

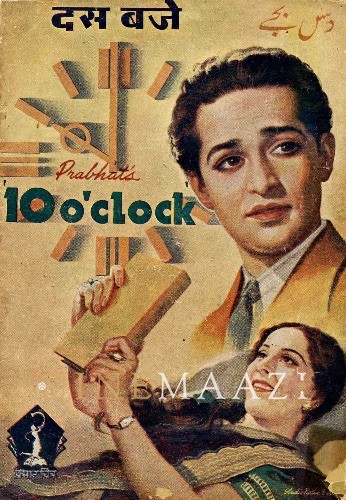

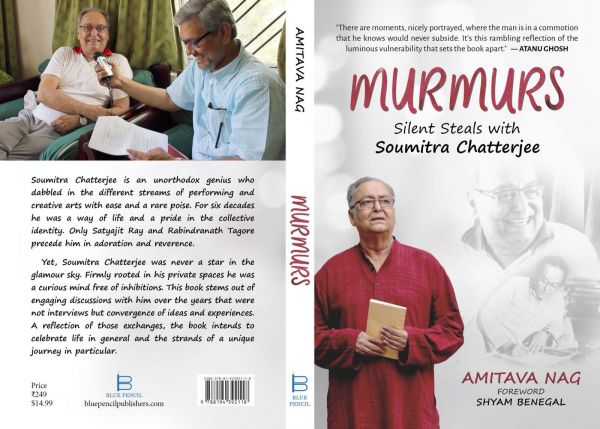

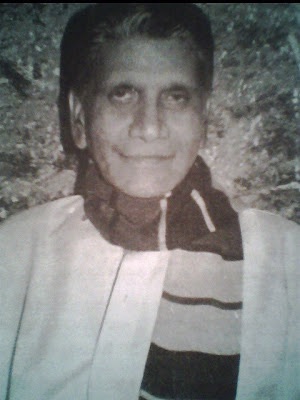

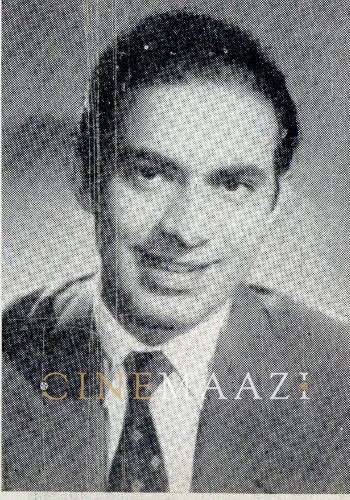

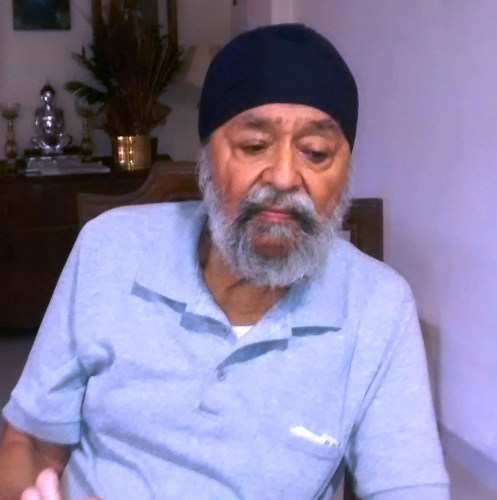

On 15 November, 2020, Indian cinema lost one of the brightest stars in its galaxy. Soumitra Chatterjee, the last mooring to a glorious past of Bengali cinema, left this world forever. A career full of immense accolades, a gallery of unforgettable characters and a principle stand to always be an actor first, a star later – these defined his legacy public memory. In many ways Amitava Nag’s new book Murmurs: Silent Steals with Soumitra Chatterjee is about how we remember. Eschewing the linear history of facts, the author presents us with snippets of his conversations with the veteran actor over the years. An elliptical, ruminative book, it is so much more than a simple memoir. The author, who has previously written Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Film Roles of Soumitra Chatterjee and translated his poems in Walking Through The Mist, gives us a glimpse of Soumitra the poet, the painter, the family man, and in turn reveals some his fears, philosophies and that undaunted reserve of strength. An introspective trek through memories rather than a recalling of career milestones, the book releases on 19th January, 2021. Below is an excerpt from the book.

‘A poet creates tragedy from his own soul, that soul which is alike in all men. It has no joy, as we understand that word, but ecstasy, which is from the contemplation of things vaster than the individual and imperfectly seen, perhaps, by all those that still live. The masks of tragedy contain neither character nor personal energy.’

– W. B. Yeats

In rejecting the self and merging the soul with the greater cosmos, a poet alleviates his tragedy. Or does he amplify it further? Isn’t the poet eternally in love and also at war, with the self, and with history? So, the question remains, what does a poet reject when he is facing rejection?

‘I have an internal safety valve which saved me from my own undoing,’ Soumitra-babu contemplates, ‘I don’t overdo things. I just take a step back from extremes. I have gradually reduced my alcohol intake for example. Actually, I am a fearful person.’

‘But that is not rejection. Control is different from rejection; don’t you think so,’ I argue back.

‘In cinema, I did reject roles on merit at times. I was never very perturbed about remunerations a role may offer. Why else do you think I rejected the offers from Bombay? Even from Hrishikesh Mukherjee. But in hindsight, a stint in Bombay would have secured the future,’ he fiddles with his ancient non-touchscreen, petite mobile phone.

‘Even not accepting the modern, is rejection. Will you reject this rejection?’ his eyes flicker a mischievous smile as he catches me looking at his mobile phone.

‘And, I have accepted many memorable roles that others rejected thinking those were not worthy of their stardom or glamour! I got the offers of Kony and Sansar Simante in that way – others’ loss, my gain. You already know these, don’t you?’

He had told me these stories earlier when I interviewed him for my book Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Film roles of Soumitra Chatterjee.

‘I do reject a lot of my poems as well. Not all that I write in a rough version make it into my fair copy and then to a manuscript. I reject most when I am drawing though. It is a new vocation for me, that’s why this love of hide and seek,’ he explains.

‘Hide and seek? In what sense?’ I probe further.

‘All that I want to draw, I can’t achieve. More or less, practicing for the last seven decades, I can achieve what I intend to, in my poems and acting.'

He picks up his square diary and shuffles pages with the earnest restlessness of a young child. He stops at a page with a drawing of a swan. I peer at the open page, the drawing is a pen sketch, very basic.

‘What I love in drawing is the fact that through it I seek truth, not the desire to prove my worth. The process asks me if the creation brings out something good in me or not. Do I enjoy doing it, or not? The question is not if the painting is valuable, precious. It is an opening Amitava. Some of my fantasies would come through the opening, along with me. A few others, probably the lofty ones, won’t be able to make it through.’

He shows what he has written at the bottom of the page – ‘Practice’.

‘I am practicing this figure that I found in the cover of commonly found exercise copies for children. This is not my original idea, just a copy to hone my skills. Only if it attains a certain level shall I put a signature and a date. Else it remains just a fun act. What will you classify it as? A rejection? To me, it is my pathway to draw better the next day.’

I can see an honest confession sweeping his face. Raw and true. Somewhere I read long back that life teaches us to take up arms, have defense, fight. Art frees us from the cudgels, disarms us. Is this process of neutralization actually an affair of rejection in essence? Because, in forgetting and saving memories for nostalgia, we do reject as well.

‘I think, in any art, or maybe in life as well, measure of love is the ability to give up,’ I tell him and the scribbles in his diary left to him and to a few visitors like me. To be forgotten and removed from memory.

‘I think I agree with you on this. Leave and let go, so you know that you are into it even stronger. Do you know the colour of strength, Amitava?’

No, I don’t. All throughout this life of mine I chased the colour of strength with futility. Now, I find him at 85, experienced and mature groping for an answer as well. Probably strength in itself is an illusion. A rejection of our fears to be weak.

A star, a galaxy of accolades and achievements. I have always believed that ‘glamour’ creates an insurmountable gap between a person and his image. For him, that space is far less than many others, probably. But again, I have not met the others so closely, even to measure their troughs.

I leave him today in his own bewilderment, one that every life must adorn. There is no expiry date on the puzzles of our mind. A working mind always works. What if a parachute ends up flying higher than the plane it escaped from?

This excerpt has been taken from Amitava Nag's Murmurs: Silent Steals with Soumitra Chatterjee published by Blue Pencil Publications.

Tags

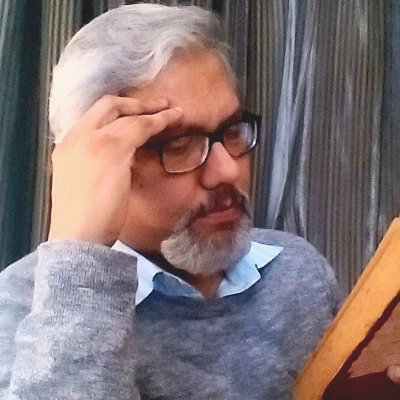

About the Author

Amitava Nag is an independent film critic and editor of film magazine 'Silhouette' (www.silhouette-magazine.com) since 2001. Till date Amitava has authored 5 books on cinema including 'Satyajit Ray's Heroes and Heroines', '16 Frames' and 'Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Films of Soumitra Chatterjee'. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in Bengali and English and authored a collection of short stories each in English and Bengali, and an anthology of Bengali poems.His first anthology of English verses and a selected translation of Soumitra Chatterjee's poems are awaiting publication.

.jpg)