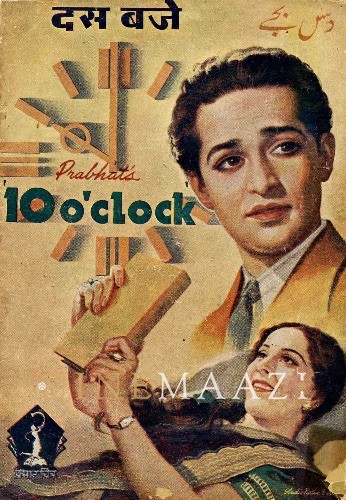

In 1953, Nirmal Dey’s romantic comedy Sare Chuattor launched a new screen couple — Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen. Most of the 20-odd films they starred in together in the 1950s were runaway hits. And, in almost all of them, there was the journey of the rural youth to the urban milieu of Calcutta in search of a better living, and finding love. The trajectory not only acted as wish fulfilment for rural West Bengal but also for a large section of Bangla refugees.

The exploration of the hero in the city of Calcutta is hence a discovery of modernity as well as an exhibition of the architecture of the city. These architectural monuments — from Victoria Memorial and Howrah Bridge to the General Post Office and several other administrative buildings — were erected during the British rule and served the added purpose of a visual treat.

In a different sense, these structures also represented the power and dominance that the hero and the heroine set out to fight against.

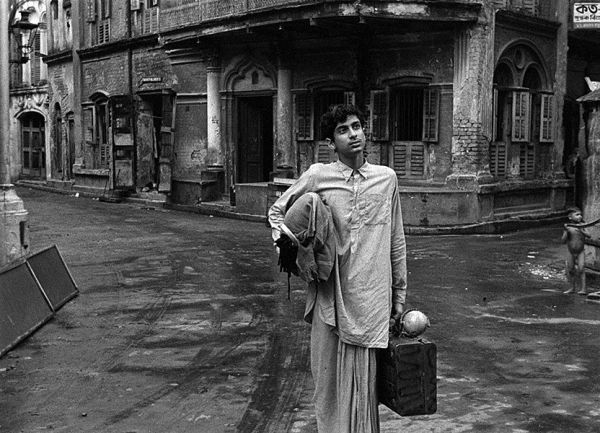

Migrating to Calcutta was the backdrop of the last two films of Satyajit Ray’s iconic Apu trilogy. While in the latter half of Aparajito (1956), we find a teenage Apu moving to the big city with dreams of a bright future, in Apur Sansar (1959), the grown-up Apu strives hard to survive the city. In Mahanagar (1963), the uncertainties of the 60s are reflected in the form of unemployment, disbelief and an erosion of innocent charm. With deft touches, Ray portrays the socio-political conflicts of the middle-class, as the domesticated housewife Arati sets out of her home for the first time to earn for her family.

For Mrinal Sen, the reality was starker. In Akash Kusum (1965), Ajay, the hero, has no apparent history of migration; he is, rather, a settled dweller with a dream of making it big. Ajay, in a sense, is an alter ego to Apu (both characters played by an eloquent Soumitra Chatterjee); a character tainted with deceit and manipulation, traits of a modern citizen in a cruel metro city.

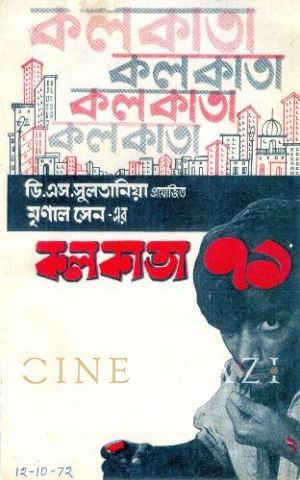

The Naxalite movement of the late 60s took its toll on Calcutta more than any other big city. Calcutta’s trinity of Ray, Sen and Ritwik Ghatak responded to the situation in their own unique styles, with Ray and Sen making Calcutta trilogies.

Jana Aranya (1976), the last in Ray’s trilogy, opens with an examination hall with Naxalite and Maoist slogans on the walls. The camera zooms in on the answer script that reads ‘Calcutta University’ — Ray’s symbolic ‘examination’ of the city in light of the political fiasco that engulfed it. Unlike Ray’s earlier films, his Calcutta trilogy is distinctly judgemental and arguably more caustic.

For Sen, Calcutta 71 (1971) was a political statement against the ills of society: “The history of India is a continuous history not of synthesis but of poverty and exploitation.” As opposed to Ray’s more classical and poetic treatment, Sen’s camera shows the narrow lanes that depict the city’s claustrophobia. In Subarnarekha (1962), two central characters embark upon a city ride that culminates in one of them meeting his long-lost sister in a prostitute colony. Is this the price one pays when one migrates to a big city?

Uttam Kumar, Bengal’s biggest matinee idol, passed away in 1980. Soon after, commercial Bengali cinema steadily started to lose focus on the city. With the super hit Shatru (1984), rural Bengal came into focus. Borrowing heavily from Hindi cinema of the 70s, these films depicted the triumph of good over evil via one honest individual. The journey that started with Uttam Kumar’s flight from the village to Calcutta in the 50s was completed when Prosenjit Chatterjee moved back to the village as an honest police officer.

Only as metaphor

In 2001, the city changed its name to Kolkata. By then, Rituparno Ghosh had emerged as a successful director of ‘parallel’ cinema. Alongside, Ghosh overhauled the visual spaces of Bengali cinema; in film after film, he showed low-key indoor settings, that helped him sustain his low-budget offerings. As a result, the city gradually disappeared physically, only to be reminisced metaphorically through references and indirect associations.

In the 2000s, Suman Mukhopadhyay’s Herbert and Mahanagar@Kolkata portray the city with angst, mystery and nostalgia. Herbert’s sensitive portrayal of North Kolkata is matched by Sthaniya Sambad’s handling of South Kolkata, which also incidentally revived the East Bengali dialect, fast dying due to homogenisation.

Cinemaazi thanks Amitava Nag for contributing this article which was originally published in The Hindu on 14 October 2017. Some images used in the article were not part of the original article. https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/movies/losing-the-city-in-cinema/article19852369.ece

Tags

About the Author

Amitava Nag is an independent film critic and editor of film magazine 'Silhouette' (www.silhouette-magazine.com) since 2001. Till date Amitava has authored 5 books on cinema including 'Satyajit Ray's Heroes and Heroines', '16 Frames' and 'Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Films of Soumitra Chatterjee'. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in Bengali and English and authored a collection of short stories each in English and Bengali, and an anthology of Bengali poems.His first anthology of English verses and a selected translation of Soumitra Chatterjee's poems are awaiting publication.

.jpg)