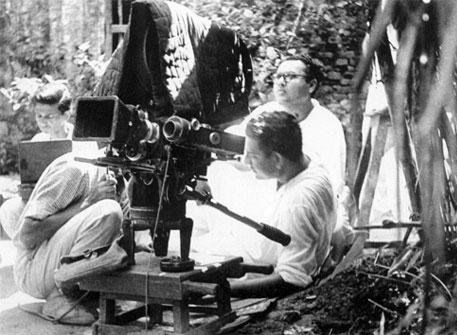

Extracted from an interview published in the Bengali journal Chitrabhash, April-December 1980. Subrata Mitra was a pioneer in Indian cinematography and shot a number of Satyajit Ray’s films up to Nayak.

The desire to become a cinematographer dates back to my schooldays. Those days, great films used to be screened in the Sunday morning shows at Basusree or Purna theatres. My friends and I frequented the ten-anna seats to watch these films. I watched some phenomenal films at the time, the kind that impacted me a lot, particularly with respect to the photography, for example, Les Miserables, Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, The Best Years of Our Lives, Wuthering Heights (all shot by Gregg Toland), Gaslight, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Random Harvest, Madame Curie, Desire Me, Mrs Miniver, Mrs Parkington (these by Joseph Ruttenberg), Robert Krasker’s pioneering cinematography in The Third Man, and Oliver Twist and Great Expectations (shot by Guy Green). I watched quite a few more than once. The low-lighting in films like Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, Gaslight, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, in particular, impressed me a lot. I sometimes wish I could see these films again today, if only to see if they cast the same magic on me now as they did then. I am not sure if these films had anything to do with igniting in my mind the thought of becoming a cinematographer.

The desire to become a cinematographer dates back to my schooldays. Those days, great films used to be screened in the Sunday morning shows at Basusree or Purna theatres. My friends and I frequented the ten-anna seats to watch these films.

Mr Gopal Sanyal was a regular at these film outings with us, though of course he was older than we were. He had returned from America after working with Burnett Guffey. After every screening, we used to have long discussions with him on photography and lighting, and he used to explain a lot of things to us. He had an important role to play in my desire to become a cinematographer.

The motor vehicle licensing offices were situated behind my house. Next to these were a number of shops that dealt with facilitating photographs, filling up forms, etc., for drivers. I was six or seven years old at the time and I used to frequent the shops. The shopkeepers were fond of me and allowed me into their dark rooms and studios. The photographed faces emerging from the developing trays in the dark room fascinated me. I am not sure what role those shops played in piquing my interest in photography.

It was in the second year I.Sc. at St Xavier’s College that I began mulling over a career as a cameraperson seriously. In an era when my friends were opting for careers in medicine and engineering, the only way for me to learn camerawork was to assist a cinematographer. Dutifully, I applied for the same with a few well-known names in Kolkata. But, for whatever reason, none of them could offer me work. I find it quite ironical that I am now deeply associated with the Film and Television Institute of India, attend an American Council meeting or two every year and conduct workshops and lecture sessions for cinematography students. I love these interactions with future cinematographers, preparing them for the world. I could not have asked for anything more if I had something like the FTII when I started out.

I was unaware of so many issues pertaining to cinematography while filming Pather Panchali – things that a first-year student at FTII will know today. I had to literally learn my way through the making of the film, experimenting all the way, discovering things for myself. Needless to say, it called for many a sleepless night.

I have heard that established cinematographers are often averse to teaching their assistants the tricks of the trade. There’s this apocryphal story about a cameraman who used to set the lens exposure himself and rush to change the aperture collar as soon as the shot was done, so that the assistant would not learn about aperture issues pertaining to a shot. Of course, these days, with books on photography more easily available, things have changed. At the same time, a lot depends on the photographer’s own aesthetics, though there’s no denying the importance of good equipment and a knowledge of basic technique. I was unaware of so many issues pertaining to cinematography while filming

Pather Panchali – things that a first-year student at FTII will know today. I had to literally learn my way through the making of the film, experimenting all the way, discovering things for myself. Needless to say, it called for many a sleepless night. Sometimes, I wonder if it comes too easy for students these days. With all the books, magazines, institutes at their disposal, do students today have the patience for a fifteen-minute lecture on what took me thirty years to learn.

Meanwhile, after I.Sc., it was time for B.Sc., for which I had neither the desire nor the aptitude. I realized it would be a waste of time. But, given my parents’ desire that I pursue a bachelor’s degree, I gave in, but on one condition: the moment I got an opportunity in cinematography, I would give up college. They agreed. In fact, my parents never denied me anything I wanted to do, be it learning to play the sitar in school or cinematography later on. If anything, a number of relatives and even the friends with whom I went on those morning shows tried to dissuade me from taking up cinematography. In fact, when work on

Pather Panchali stalled midway, many of them said, ‘Now, didn’t we tell you! You should have listened to us.’ Of course, I understand where they were coming from. For one, the profession was notoriously uncertain. An A-lister could somehow manage to make a living, but for run-of-the-mill cameramen, it could be tough. Also, cinema was not looked upon with respect as a profession. However, perceptions regarding a career in cinema have changed considerably, and I feel that

Pather Panchali has a lot to do with it.

The profession was notoriously uncertain. An A-lister could somehow manage to make a living, but for run-of-the-mill cameramen, it could be tough. Also, cinema was not looked upon with respect as a profession.

While doing my B.Sc., I came to know that acclaimed French film-maker Jean Renoir had arrived in the city to shoot his film

The River. This was in 1950. My father took me to meet its American producer McEldowney, who said, ‘I have no issues with you apprenticing on the film, but you will have to seek the director’s permission.’ Subsequently, I met Renoir, who too had no objections. However, he suggested that since I wanted to learn camerawork, I should work with the cameraman, Claude Renoir, his nephew. Claude Renoir expressed some doubts, given my inexperience. He said, ‘You will have problems with the nitty-gritty of the work involved. No one will allow you to touch such expensive equipment.’

The film was being shot in Technicolor, involving a complicated camera. In fact, Technicolor Company had deputed two technical advisors who were responsible for handling the camera. Claude, however, had no problems with me attending the shoot as an observer. I started going to the shoot every day. The entire film was shot in a bungalow near the Ganga in Barrackpore and at Eastern Talkies Studios in Dakshineshwar. I made it a habit to record all camera movements, sketching the same, lighting patterns, etc., in a notebook.

There’s a world of difference between today’s Eastmancolor and yesteryear’s Technicolor. Not only did it require a special camera which only Technicolor Company manufactured, the film speed was quite slow. It needed a lot of light. I heard that Claude had great difficulty in the absence of sufficient natural light, though I was too much of a novice to realize it on my own.

This was my first experience of a film shoot and it was in colour! I eventually debuted as a cameraman with a black and white film. Interestingly, though Claude Renoir was a well-known cinematographer, this was the first time he was shooting in colour. There’s a world of difference between today’s Eastmancolor and yesteryear’s Technicolor. Not only did it require a special camera which only Technicolor Company manufactured, the film speed was quite slow. It needed a lot of light. I heard that Claude had great difficulty in the absence of sufficient natural light, though I was too much of a novice to realize it on my own. Like a good student, I kept making my notes studiously, thinking it would stand me in good stead in the future. Though I had little use for these notes going ahead, my notebook proved quite useful to Claude. One day, in the middle of a break in shooting, Jean Renoir happened to discover my ‘priceless’ notebook. Visibly happy and excited, he called for Claude. Claude too was astonished with my efforts at documenting the camerawork. A few days after this, Claude had to redo a shot. He called for my notebook and used it as a reference to get the lighting right.

Though watching the shoot was a learning experience, there was precious little I learnt about complicated aspects pertaining to lighting and camerawork. What really inspired me was the intensity and devotion that two of the world’s finest film-maker cameramen brought to their work. Making a film was almost a matter of faith with them. At that impressionable age, I could not have asked for a better initiation into cinema. It shaped my approach to cinema. My attitude to film-making would probably have been different if I had started with any other run-of-the-mill film.

What really inspired me was the intensity and devotion that two of the world’s finest film-maker cameramen brought to their work. Making a film was almost a matter of faith with them. At that impressionable age, I could not have asked for a better initiation into cinema.

It was during the making of

The River that I first met Satyajit Ray. He was at the time art director at D.J. Keymer. Though our families knew each other, I had never met him before. He was a fan of Renoir and would make his way to Barrackpore on Saturdays and Sundays or whenever he found time to do so.

Bansi Chandragupta was the art director for

The River. Bansi-babu and Satyajit Ray knew each other. Since Manik-da did not find time to attend the shoot every day but was keen to know what was happening, I often went to his home in the evenings to discuss the film with him. He was an avid listener and expressed a great deal of interest in the photographs of the shoot that I took. He was very supportive of my photography and often told me, ‘You have developed an eye.’ Over time, we established a close rapport.

Around the same time I heard about his plans to make

Pather Panchali. And he assured me that I would work on the film. However, I wasn’t going to be the cameraman. Manik-da told me that he had

Nemai Ghosh in mind as cinematographer and I would be his third or fourth assistant. I remember I was over the moon. In fact, I wonder if I was more happy to have been selected as assistant to Nemai Ghosh than I was when Manik-da later asked me to take over as cameraman.

However, Pather Panchali took some time getting started. In the meantime, Nemai Ghosh shifted to Madras and began working there. Suddenly one evening, Manik-da said to me, ‘Why don’t you shoot the film?’ Needless to say, I nearly fell off my chair. I even tried to dissuade him.

However,

Pather Panchali took some time getting started. In the meantime, Nemai Ghosh shifted to Madras and began working there. Suddenly one evening, Manik-da said to me, ‘Why don’t you shoot the film?’ Needless to say, I nearly fell off my chair. I even tried to dissuade him. I told him that I knew next to nothing about cinematography. He responded, ‘You do still photography, don’t you? Where’s the difference? Here, you just press a switch and the camera starts rolling. The rest is the same, isn’t it?’ Even if I could not reason with him that day, no sooner had the shooting commenced than we realized how different still photography was from cinematography. In the former, neither the subject nor the camera moves. In a film, everything is fluid and the lighting requirements change within a shot too. But by now it was too late to do anything.

I am sure Manik-da must have been roundly admonished by his friends, relatives and well-wishers for his decision to employ me as cinematographer. As it is, this was his first film as director and he had no experience. And I was a twenty-one-year-old novice who had not even touched a movie camera. I do not blame them. I would have said the same thing if I was in their shoes. In fact, I wonder if anything remotely like this has ever happened in moviemaking circles. Yet, if I had not been asked to jump into the fire, so to speak, I do not think I could have become a cameraman. More than confidence in my abilities, Manik-da had confidence in himself. And a sense of adventure. There was probably some other reason too. Because he was inexperienced, he was a little worried about working with an experienced, well-known cameraman. When Manik-da was making the rounds of producers and distributors’ offices for funds before starting the film, a number of these experienced hands had scoffed at his ideas. For example, they had laughed off his decision to shoot the rain sequence outdoors. ‘You are mistaken. One does not shoot like this, it’s not done,’ he was told.

Yet, if I had not been asked to jump into the fire, so to speak, I do not think I could have become a cameraman. More than confidence in my abilities, Manik-da had confidence in himself. And a sense of adventure.

A lot of rumours pertaining to me went floating around in the initial days of the shoot. A number of people were convinced that I would not be able to shoot anything, or even if I did, it would not be worth the roll it was shot on! I remember vividly the experience of watching the rush print of the first day’s shoot at Bengal Film Laboratory. The few moments between the lights dimming and the first shot appearing on screen seemed interminable. Even a Hitchcock film could not have been more suspenseful. While planning a shot or lighting, one often wonders if one is going about it the right way. Could it be done differently, better? Watching the kaash sway in the rush print, all such thoughts were stilled. I am not sure anyone of us would feel such joy ever again.…

I remember vividly the experience of watching the rush print of the first day’s shoot at Bengal Film Laboratory. The few moments between the lights dimming and the first shot appearing on screen seemed interminable. Even a Hitchcock film could not have been more suspenseful.

One of the many things that today astound me about shooting

Pather Panchali was that we actually shot the film with a camera as heavy as the Mitchell. No cameraman today would do it. I myself won’t. Yet, at the time it made no difference. We shot in the rain lugging the Mitchell, we chased grasshoppers. An Arriflex would have made it so much easier. I eventually moved on to the Arriflex with

Aparajito, probably the first full-length feature film in India shot on the Arriflex. Manik-da and I had discussed the possibility of buying an Arriflex after

Pather Panchali. I, of course, had no money. For

Pather Panchali, which we shot for over a period of four years, I received a received a princely sum of Rs 450 per month for just three months – after the Government of West Bengal came in to finance the film. In fact, I borrowed a considerable sum of money from my father to shoot

Pather Panchali. I remember the production manager Anil-babu telling me often on the way back home from Manik-da’s, ‘Subrata-babu, we need so much money tomorrow or else we won’t be able to shoot.’ So, it was exciting to plan buying an Arriflex with Manik-da. However, Manik-da eventually backed out, citing inability to manage funds for the same. By this time, I was obsessed with buying one, and I proceeded to do so on instalment. It is of course another matter that the twenty-month instalment was quite a pain. The camera still operates and Manik-da’s latest film

Hirak Rajar Deshe has been shot on it.

Another remarkable feature of the Pather Panchali shoot was that we shot almost all of it outdoors. Barring a few night shots, all sequences were shot at Boral. That called for a number of lighting innovations.

Another remarkable feature of the

Pather Panchali shoot was that we shot almost all of it outdoors. Barring a few night shots, all sequences were shot at Boral. That called for a number of lighting innovations. We had to perforce use artificial lighting for a few indoor shots, but these were not the halogens we use today or the standard studio lights in use at the time. The Government of West Bengal had by then taken over the film. An officer at the Writers’ Building assured us of being able to arrange the lighting for us. We were so cash-strapped that none of us worried about the quality of lights – that we were managing at all was a blessing. Imagine my horror when the lights arrived and I discovered that they were police searchlights! Needless to say, they were unsuitable for any film shooting. There was no way the light they cast would appear natural. So, there was no option but to use white cloth over the lights. Consider the scene where a sick Durga, lying in the room, is watching the sweetmeat seller through the window. It was necessary in this scene to have some light on Durga to balance the light on the trees, sky, outside. Moreover, the scene of Durga’s death the day after was also shot with these searchlights. In contrast with the strong natural light outdoors, the light from the searchlights inside was quite weak. Yet, there was no way to balance the low light indoors with the bright one outside. We had no option but to wait for the light outside to dim.

In the death scene you will notice that the room is lit by a lamp; outside, there’s a squall. We tried our best to approximate the lights to these conditions. For the lightning, however, we desisted from using the standard process in use at the time, which involved switching a light on and off. If you observe lightning closely, the effect is more continuous; not quite a switch going on and off. To get the effect, we kept the studio lightning lights on and placed two men with cutters in front of each light. The men were tasked with shielding the lights and then removing the cutters, and that gave us the required effect.

Pandit Ravi Shankar, returning to India, had written down the notations for some of the film’s theme music on his plane ticket. The second tune that he played during the recording is what we know as the Pather Panchali theme. I had never heard a more beautiful theme music for any film till then.

Pather Panchali also put my music skills to test. I have already mentioned learning the sitar in school. How was I to know that it would bear fruit in the film, where I ended up playing the sitar in two scenes? The music recording for the entire film was literally done overnight.

Pandit Ravi Shankar, returning to India, had written down the notations for some of the film’s theme music on his plane ticket. The second tune that he played during the recording is what we know as the

Pather Panchali theme. I had never heard a more beautiful theme music for any film till then. Today, one cannot imagine the film without this. We finished composing, rehearsing and recording the music in one night as Ravi Shankar was scheduled to leave the next day. Later, while editing, we discovered that we were running short of music in two places. Ravi Shankar was no longer available. And Manik-da zeroed in on me. I protested, citing my lack of practice. Manik-da said, ‘Doesn’t matter, just play.’

Later, while editing, we discovered that we were running short of music in two places. Ravi Shankar was no longer available. And Manik-da zeroed in on me. I protested, citing my lack of practice. Manik-da said, ‘Doesn’t matter, just play.’

I composed the music that accompanies the sweetmeat seller and played the sitar for the piece – a simple piece, but it became very popular. Later, Ravi Shankar complimented me saying, ‘Many people abroad have complimented me for

Pather Panchali’s music, citing the sweetmeat seller theme in particular. I often disabuse them of the perception. But at times, I say nothing and ingeniously take credit for it.’ I also played the sitar in the scene where Apu and Durga are sleeping and Sarbajaya opens a box and takes out old utensils which she would pawn the next day. By the way, I had played the sitar in two scenes in

The River too.

Shooting

Pather Panchali was a long struggle from beginning to end. Work stopped midway for a year and a half for lack of funds. I don’t think there’s a producer we did not approach – some didn’t like the film at all; for others, it didn’t work as a business proposition. The stories are now legion. The whole unit functioned like a family. Each member was assigned a unit – art, camera, production, etc. Yet, nothing stopped anyone from working with another department if the need arose. How can I forget Bansi Chandragupta, standing on a crumbling wall, reflector in hand, trying lighting patterns? The piece of cloth that Apu lies on was the one I had used as an infant. What both Manik-da and I struggled most against was our own inexperience. We had no knowledge of film-making. Every shot was a test that kept us awake all night. Of course, money was a problem, but even if we had money, making the film would have been as arduous a task, given our inexperience. Yet, at the end of the day, none of us will ever forget the ecstasy of working on the film.

Translation by Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri

.jpg)