Jyotiprasad Agarwala: The Father of Assamese Cinema

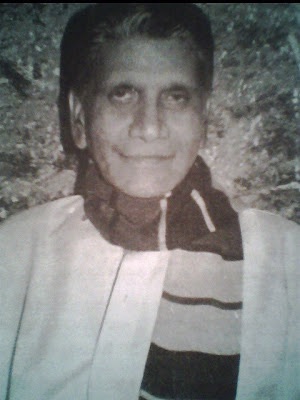

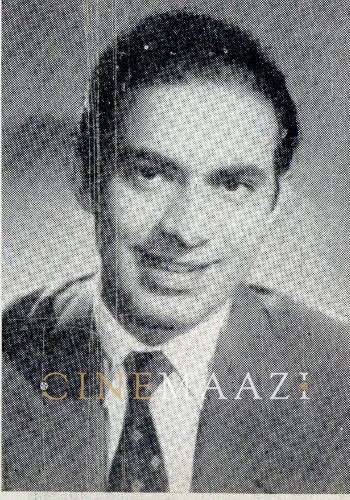

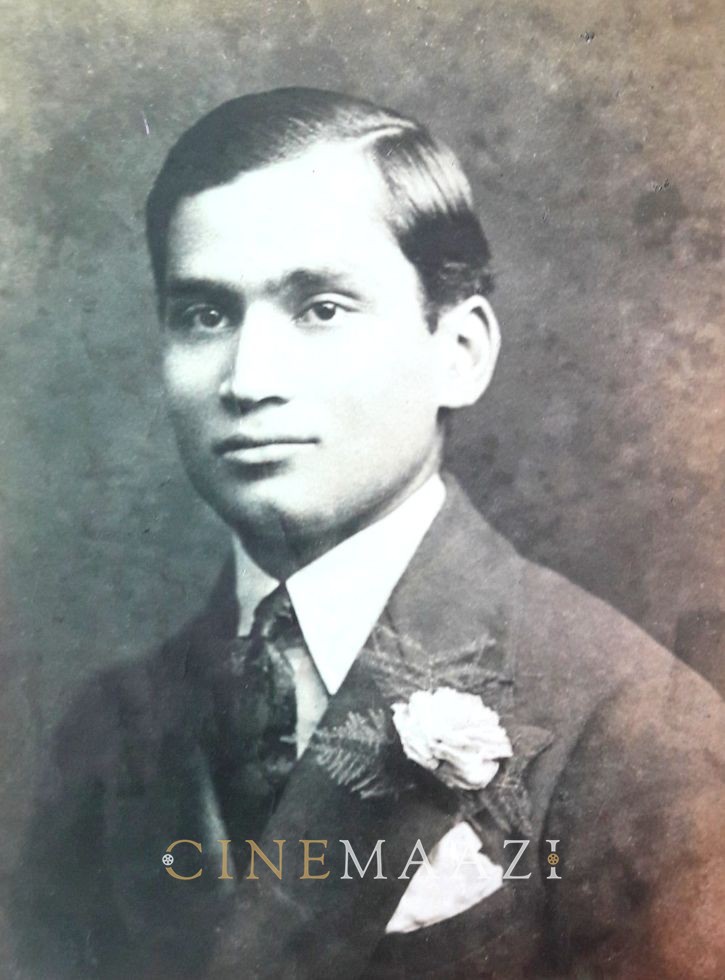

Jyotiprasad Agarwala emerged as a new voice of modern Assam and brought about a renaissance in the realm of art and culture of the region. He was a playwright, musician and composer, poet, patriot and director.

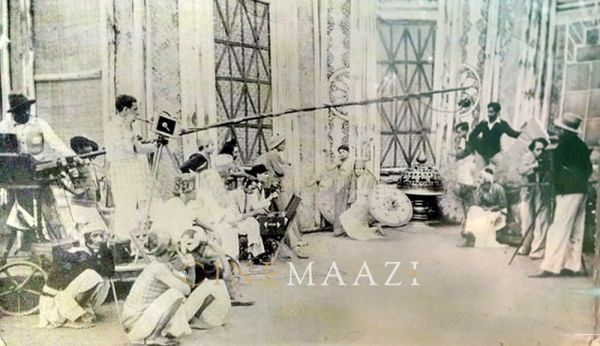

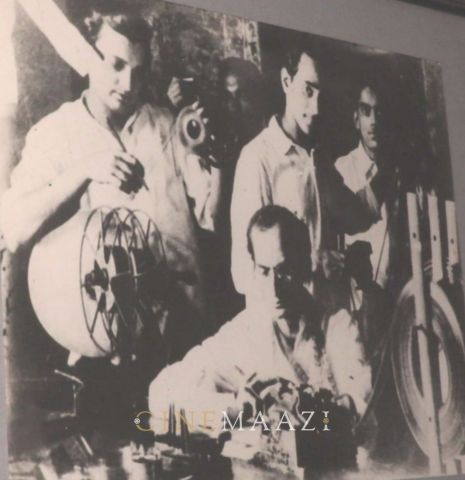

Jyotiprasad was born on 17 June 1903 in the Tamulbari Tea Estate of Dibrugarh in an affluent family. His father Paramananda Agarwala was adept at playing different musical instruments, while his mother Kiranmoyee too sang folksongs. He went to Edinburgh University in September 1926 for his MA studies. He stayed in Edinburgh from 1926 to 1930 and visited the UFA studio in Berlin, Germany, to acquaint himself with film-making techniques.

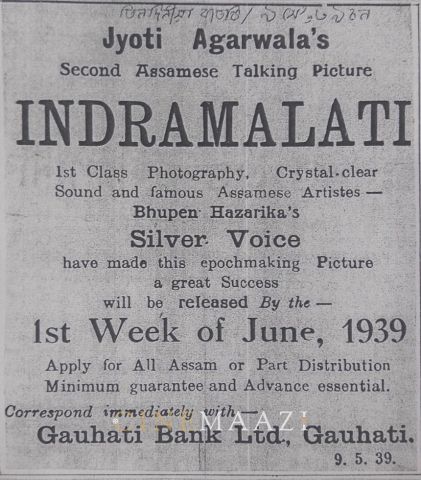

Based on his own story, Indramalati, set in the town of Tezpur, narrates the story of love between Indrajit Barua and Malati. Indrajit’s father Mahendra Nath Barua, a famous barrister, brings him up as a single parent after his mother’s demise. Indrajit, an attractive young boy, studies at a college in Calcutta. During his summer vacation, he comes to Tezpur and also visits his uncle’s house at Sonapur. There, he meets a village girl, Malati, the daughter of his father’s childhood friend. He spends a few days in his uncle’s house and gradually falls in love with Malati. He goes back to Calcutta for his studies, leaving Malati in the village. In the meantime, Chandiram, a rich farmer’s son in Sonapur, takes advantage of Indrajit’s absence and proposes marriage to Malati. When both Malati and her father reject his advances, Chandiram kidnaps Malati and takes her to a nearby tribal village. Hearing about this, Indrajit reaches Sonapur with his friend Lalit from Calcutta. After a long search, he rescues his beloved Malati.

Jyotiprasad arranged a special screening of Indramalati in Guwahati on Sunday, 30 July 1939, at 4 p.m. A newspaper article said that the film would be officially released on 1 August in Sati Talkies. The film was relatively successful. In contrast to Joymoti’s historical dimension, Indramalati focused on a simple theme of romance and yet won the hearts of the Assamese audience.

Jyotiprasad re-edited Joymoti in 1948 in Calcutta with the addition of new songs. A new set of people were engaged in the venture: Santosh Banerjee as sound recordist, Ajay Chaliha as assistant editor and Dilip Sarma as assistant music director. Initially, they thought of replacing the character of Joymoti in the second edition, a fact that can be gleaned from the advertisement in a newspaper asking for auditions for the role of Joymoti. But they dropped the idea. He wanted to do the re-editing work at Aurora Film Corporation of Calcutta. Aurora Film Corporation wrote to Jyotiprasad, ‘It is gratifying to note that you intend to re-take certain scenes of Joymoti and also to produce another new Assamese film in our studio.’ Senola Musical Products Co. of Calcutta asked Jyotiprasad to transfer the right for the recording of the songs: ‘Xunore palengot o monetora’ and ‘Luitore pani jabi oi boi’. They also asked permission to release the disc under their label, offering a royalty of five per cent on the net sale. Newspaper advertisements and circulars were distributed about the arrival of the re-edited Joymoti which was released on 28 May 1949 at Elli Cinema Hall, Jorhat. This time, the response was warm.

Jyotiprasad Agarwala made just two films in his lifetime, and yet pioneered cinema in Assam. He planned to make other films based on his own scripts, which unfortunately never took off. These include The Dance of Art, which he had submitted at UFA, Berlin; The Sanyasin; a Hindi and Bengali version each of Joymoti; Aamar Gaon; Kanaklata; Luitor Paror Agnixur/ Manor Dinor Agnixur (based on his story ‘Sandhya’). He also wrote two articles on cinema titled ‘The Film Industry of Assam’ and ‘The Responsibility of Assamese Audience towards the Making of Assamese Film Industry’.

He breathed his last on 17 January 1951, leaving behind two sons and three daughters. On 17 June 2004, the Government of India released a commemorative postage stamp on the birth anniversary of Jyotiprasad Agarwala for his contribution in the field of the art, culture and literature of Assam.

Tags

About the Author

Parthajit Baruah is an Indian film scholar and documentary filmmaker. He won the Assam State Best Film Critic Award for his book Face to Face: The Cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan (HarperCollins 2016), and the Prag Channel Best Film critic Award for his book Chalachitror Taranga (Assamese). He did two film research projects at NFAI, Pune. He has presented papers on cinema at various international conferences. His article 'Shakespeare in Assamese Cinema' (Shakespeare and Indian Cinema, 2019) was published by Routledge Publishing House. His documentaries have won many awards at International Film Festivals. He teaches English and Cinema at Renaissance Junior College, Assam. He is a member of FIPRESCI.

.jpg)