The Everyman: Rashid Khan and His Art

19 May, 2020 | Long Features by Sumant Batra

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

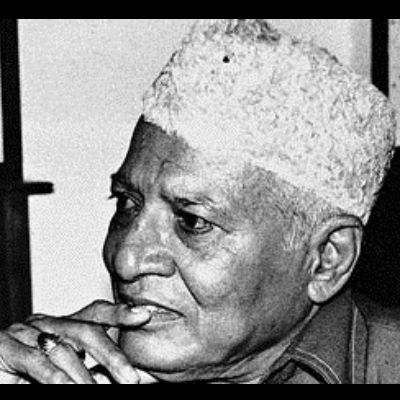

Many films made through the 1940s to the ’70s often cast a thin and lean short-statured man with an unmistakable presence. Standing next to the biggest stars of the era, he exuded a cool confidence, and despite his nondescript appearance the viewer’s eyes would invariably veer towards him. Those familiar with movies of this period would distinctly remember the opening scene of Navketan’s Baazi (1951) in which Pedro, ‘dressed in a sharp suit of the kind favoured by the gangsters in American cinema’ emerges from a chauffeur-driven Ford, holding a cane and cigarette holder. He casually lights a cigarette, walks past a man (Guru Dutt) sitting on his haunches and steps inside a dingy structure to survey Madan’s (Dev Anand) gambling skills. That was Rashid Khan (also credited as Rasheed Ahmed or Rasheed in many movies), a prominent character actor of the era, who played many memorable roles in over 85 films but regrettably remains largely forgotten today.

A gifted actor who conveyed an effortless ease, Rashid did not let his non-‘filmy’ looks and lack of formal training come in the way of his vocation. Often cast as the hero’s sidekick, he always managed to make his presence felt, irrespective of the length of his role.

Though there is some doubt over the year of his birth, as he himself stated in an interview, most available records mention 5 July 1915 as the date. Born into a poor family in Baroda, Gujarat (then Saurashtra), his childhood was full of difficulties and struggle. Rashid was forced to quit school early when his parents could no longer afford to pay for his education. ‘As I moved to the next classes, the fees and expense too kept going up forcing me to drop out of school,’ the actor once reminisced. Even when he was in school, he had no time to study. To earn some extra money to support the family, he had to make cardboard boxes when he returned from his day at school. After having to quit school, he took up any odd job that came his way, mostly working as a coolie to make ends meet.

Though there is some doubt over the year of his birth, as he himself stated in an interview, most available records mention 5 July 1915 as the date. Born into a poor family in Baroda, Gujarat (then Saurashtra), his childhood was full of difficulties and struggle. Rashid was forced to quit school early when his parents could no longer afford to pay for his education. ‘As I moved to the next classes, the fees and expense too kept going up forcing me to drop out of school,’ the actor once reminisced. Even when he was in school, he had no time to study. To earn some extra money to support the family, he had to make cardboard boxes when he returned from his day at school. After having to quit school, he took up any odd job that came his way, mostly working as a coolie to make ends meet.

Even when he was in school, he had no time to study. To earn some extra money to support the family, he had to make cardboard boxes when he returned from his day at school.

Rashid wanted to become a painter. Though he enjoyed acting, he had no interest in taking it up as a career. He even rejected an offer to join films by none other than Dr Ambalal Patel, a partner in Sagar Movietone, very early in life. The actor recalled a school trip to Pavagadh (near Baroda) for a scout camp, where the students staged a skit. Rashid played the role of a mute sugar salesman. Dr Ambalal Patel, who was amongst the audience, was very impressed with Rashid’s acting skills, and made an on-the-spot offer to the young boy to join Sagar Movietone. Khan declined. ‘Acting is my hobby, I have no intention to take it up as a profession,’ he told Patel. However, destiny willed otherwise.

Someone who knew Rashid introduced him to Abdul Hussain Bori, a painter in Bombay who coloured select scenes in film reels. This was the time when films were made in black and wide, and the world of Eastman Color was yet to be discovered. Filmmakers, however, had discovered the technique of introducing coloured parts into selected scenes in their films, usually a song or dance sequence, by getting them hand-painted by artists as part of post-production. Bori was one such artist. ‘Miyan kuch aata vata bhee hai? (Do you even know how to do this, young man?),’ the artist inquired of the teenager when they met. ‘Give me a chance, I promise I will learn quickly,’ Rashid replied confidently. He was hired. Rashid picked up the art quickly and was soon painting reels by himself. While working with Bori, he was once tasked with delivering prints of Nadira (1934, starring Madhuri and E. Billimoria) to Ranjit Movietone. On the way, he saw posters of an English film outside a Pathe movie theatre and decided to watch the film. He kept the print under his seat but forgot to retrieve it after the show ended. It was after he had reached Parel that he realized that he had forgotten the box. He went back to recover the box. There was a different gatekeeper on duty. He persuaded the gatekeeper to let him in but did not find the box. ‘That day for the first time I felt the earth slip away from under my feet.’ Rashid somehow reached the manager’s room. Only after being convinced that the print indeed belonged to Rashid, did the manager handed it over to him.

He kept the print under his seat but forgot to retrieve it after the show ended. It was after he had reached Parel that he realized that he had forgotten the box...‘That day for the first time I felt the earth slip away from under my feet.’

Painting, however, did not pay enough for survival in Bombay. Around that time, he came in contact with S.K. Prem, a struggling actor. They became friends. Prem introduced Rashid to M.A. Lateef, then a programme assistant in the Bombay station of All India Radio (AIR). Lateef hired him to help in the production of programmes for women and children. While working at AIR, Rashid became involved with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA).

Balraj Sahni, a prominent member of IPTA, who had returned from London after a stint with the British Broadcasting Corporation, had been invited by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas to direct Zubeida, a play based on the story of a Muslim girl from Malabar. He was looking for the right people to cast in the play. In his autobiography, Sahni writes that Mir Sahab, Mirza, Munshi Bedil and Seth Sahab were the more colourful characters of the play. He wanted Abbas himself to play Mir’s role and Rashid Khan to play Munshi Bedil. Initially resistant, Abbas relented after Sahni ‘managed to break down his resistance’, but Rashid declined and wouldn’t budge. ‘I had my most fascinating experience, however, when looking for someone who could do justice to the part of Munshi Bedil,’ Balraj Sahni recounts in the book.

As Sahni writes, he first saw the ‘thin, short-statured’ Rashid in India Coffee House talking to Chetan Anand. The moment he saw him, he knew that Rashid, ‘an exact replica of Munshi Bedil’, was the perfect choice to play the role and invited him to come on board. But ‘the man would have nothing to do with it.'

Balraj Sahni, a prominent member of IPTA, who had returned from London after a stint with the British Broadcasting Corporation, had been invited by Khwaja Ahmad Abbas to direct Zubeida, a play based on the story of a Muslim girl from Malabar. He was looking for the right people to cast in the play. In his autobiography, Sahni writes that Mir Sahab, Mirza, Munshi Bedil and Seth Sahab were the more colourful characters of the play. He wanted Abbas himself to play Mir’s role and Rashid Khan to play Munshi Bedil. Initially resistant, Abbas relented after Sahni ‘managed to break down his resistance’, but Rashid declined and wouldn’t budge. ‘I had my most fascinating experience, however, when looking for someone who could do justice to the part of Munshi Bedil,’ Balraj Sahni recounts in the book.

As Sahni writes, he first saw the ‘thin, short-statured’ Rashid in India Coffee House talking to Chetan Anand. The moment he saw him, he knew that Rashid, ‘an exact replica of Munshi Bedil’, was the perfect choice to play the role and invited him to come on board. But ‘the man would have nothing to do with it.'

The moment he saw him, he knew that Rashid, ‘an exact replica of Munshi Bedil’, was the perfect choice to play the role and invited him to come on board. But ‘the man would have nothing to do with it.'

Rashid did not want to put his radio job at risk by taking up acting. He had seen extreme poverty and struggle throughout his life and was content with the job he had finally settled into. ‘Look,’ he told Sahni, ‘acting in films or plays is the last thing I want to do now. I am not going to let them ruin me once again. My job on Radio fetches me two meals a day and they mean more to me than anything else in life. No sir, I am not going to risk losing my job for the sake of any acting role!’ Sahni persisted.

‘But,’ Sahni tried to plead with him, ‘how is acting in a play like ours going to put your job in jeopardy? Our other artistes too have jobs!’

‘Well, I don’t know about them,’ Rashid replied.

‘Listen, now that I have met you, I can’t possibly bring myself to engage anyone else for that role. Tell me, what am I to do now?’

‘I’ll tell you what,’ Rashid told Sahni, without batting an eyelid. ‘Go to hell!’

As the play moved into rehearsals, Sahni waited for Rashid to relent. A friend of Zulfiqar Ali Bukhari, the programme director at Bombay station of AIR, Sahni was a frequent visitor to the station. Whenever he saw Rashid, he would beg him to join the troupe. Rashid stayed as adamant as ever. But so did Sahni. ‘More often than not, he would threaten to call the police. Indeed, a couple of times he had me turned out of his room by a chaprasi! Still I did not lose patience. I could, of course, have got someone higher up in the radio hierarchy to make him act in our play but I did not consider that proper.’

‘But,’ Sahni tried to plead with him, ‘how is acting in a play like ours going to put your job in jeopardy? Our other artistes too have jobs!’

‘Well, I don’t know about them,’ Rashid replied.

‘Listen, now that I have met you, I can’t possibly bring myself to engage anyone else for that role. Tell me, what am I to do now?’

‘I’ll tell you what,’ Rashid told Sahni, without batting an eyelid. ‘Go to hell!’

As the play moved into rehearsals, Sahni waited for Rashid to relent. A friend of Zulfiqar Ali Bukhari, the programme director at Bombay station of AIR, Sahni was a frequent visitor to the station. Whenever he saw Rashid, he would beg him to join the troupe. Rashid stayed as adamant as ever. But so did Sahni. ‘More often than not, he would threaten to call the police. Indeed, a couple of times he had me turned out of his room by a chaprasi! Still I did not lose patience. I could, of course, have got someone higher up in the radio hierarchy to make him act in our play but I did not consider that proper.’

‘More often than not, he would threaten to call the police. Indeed, a couple of times he had me turned out of his room by a chaprasi!'

All this time, the fate of Munshi Bedil continued to hang in balance. His crew was starting to lose patience and insisted he look for another option. Balraj Sahni was determined to wait for Rashid.

Sahni’s perseverance eventually paid off. Just four days before the premiere, Rashid, an artiste by heart, took pity on a fellow-artiste and gave in. Zubeida got its Munshi Bedil, and Rashid, his first performance on a big stage.

Sahni’s perseverance eventually paid off. Just four days before the premiere, Rashid, an artiste by heart, took pity on a fellow-artiste and gave in. Zubeida got its Munshi Bedil, and Rashid, his first performance on a big stage.

Sahni then goes on to narrate the interesting experience of preparing Rashid. He writes: ‘But how was he going to learn his lines in so short a time? Here Munshi Bedil’s passion for newspapers came in handy. In no scene had Abbas shown him without holding a newspaper in his hand. All that Rashid had to do then was to read his lines off a sheet of paper, which could be easily hidden between the pages of his “newspaper”.’ The stratagem worked so well that no one from the audience noticed anything amiss. Rashid played his part to perfection. Sahni writes, ‘Much of the success and popularity of Zubeida was due to the aplomb with which Rashid played Munshi Bedil.’

He further writes, ‘Came the day of the premiere and still the play had not become a “finished product”. As if this were not enough, Chetan (Anand), the hero of the play, had a sudden attack of asthma, minutes before the curtain was to rise. In record time, I put on make-up and stepped into his shoes. As luck would have it, I had invited my younger brother Bhishma to Bombay for the premiere. He too contributed to it substantially, in that he played three different minor roles. In one of the scenes, he had to play a municipal employee, whose job it was to see to street lighting. When he appears on the stage, he finds Mir Sahab, Mirza, Seth Sahab and Munshi Bedil seated under a lamp-post, gossiping. He and Munshi Bedil get to talking. Neither Bhishma nor Rashid had any idea what the script required them to say, so they just said whatever came into their heads. This improvisation turned out to be so natural that it became part of the play, replacing the original conversation as written by Abbas.’

He further writes, ‘Came the day of the premiere and still the play had not become a “finished product”. As if this were not enough, Chetan (Anand), the hero of the play, had a sudden attack of asthma, minutes before the curtain was to rise. In record time, I put on make-up and stepped into his shoes. As luck would have it, I had invited my younger brother Bhishma to Bombay for the premiere. He too contributed to it substantially, in that he played three different minor roles. In one of the scenes, he had to play a municipal employee, whose job it was to see to street lighting. When he appears on the stage, he finds Mir Sahab, Mirza, Seth Sahab and Munshi Bedil seated under a lamp-post, gossiping. He and Munshi Bedil get to talking. Neither Bhishma nor Rashid had any idea what the script required them to say, so they just said whatever came into their heads. This improvisation turned out to be so natural that it became part of the play, replacing the original conversation as written by Abbas.’

'Neither Bhishma nor Rashid had any idea what the script required them to say, so they just said whatever came into their heads. This improvisation turned out to be so natural that it became part of the play, replacing the original conversation as written by Abbas.’

Encouraged by the success of Zubeida, IPTA decided to venture into films and thus was born the idea for Dharti Ke Lal (1946). Produced as a cooperative venture by members of IPTA, the film was Abbas’s directorial debut. Set against the backdrop of the Bengal famine of 1943, it was based on the IPTA play Nabanna (New Harvest) by Bijon Bhattacharya, and a Hindi story, Annadata (Foodgiver) by Kishen Chander. Rashid was invited to play a part in the film. The actor in Rashid had tasted blood. He did not refuse this time. He enacted the role of a wise priest who also takes a keen interest in teaching the village children. The priest loses his mind after his family dies in the famine.

Rashid Khan’s film career had started. Dharti Ke Lal released in August 1946. Rashid had by now made an acquaintance with scores of writers, poets and artists in the film industry. Roles started coming his way.

Although he had already worked in a few popular films after Dharti Ke Lal, it was Baazi, Guru Dutt’s directorial debut, that provided Rashid instant recognition. He was a rage as Pedro, the mysterious, shadowy criminal who owns the Star Hotel where Madan (Dev Anand) plies his trade as a gambler.

Although he had already worked in a few popular films after Dharti Ke Lal, it was Baazi, Guru Dutt’s directorial debut, that provided Rashid instant recognition. He was a rage as Pedro, the mysterious, shadowy criminal who owns the Star Hotel where Madan (Dev Anand) plies his trade as a gambler.

Rashid Khan’s association with Navketan had started with Afsar (1950) and with the success of Baazi he became a regular fixture in most films produced under the banner, a perfect foil to its debonair star Dev Anand. Rashid stood out in every part he graced. He won hearts as Madan Gopal, the ‘flute-playing’ assistant to architect Dev Anand in the romantic comedy Tere Ghar Ke Samne (1963). As Kalu, who sells movie tickets in black in Kala Bazar (1960), dressed in a crew neck T-shirt and a baseball cap, he had a standout bit in the hit song Teri dhum har kahin. Rashid Khan was the compulsive gambler and perpetual loser in Taxi Driver (1954) always borrowing money from Shankar (Dev Anand) as well as John the bartender in the Officer’s Mess in Hum Dono (1961).

Not surprisingly, Dev Anand and Rashid became good friends. It is said that when Lata Mangeshkar refused to sing for Navketan (due to differences with Jaidev), it was Rashid whom Dev Anand deputed to persuade the singer to change her mind. If this is true, it only goes to show the stature Rashid had acquired. It is a different matter that Lata Mangeshkar did not relent and it was only later, on Dev Anand’s personal intervention, that the singer agreed to sing in Hum Dono.

Dev Anand and Rashid became good friends. It is said that when Lata Mangeshkar refused to sing for Navketan, it was Rashid whom Dev Anand deputed to persuade the singer to change her mind.

Rashid continued to work in films by other prominent filmmakers like Balraj Sahni, Guru Dutt, Bimal Roy, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Raj Kapoor, Shakti Samanta, Raj Khosla and Moni Bhattacharya. He also acted alongside many other big stars like Raj Kapoor, Amitabh Bachchan, Shammi Kapoor, Vinod Khanna and Shashi Kapoor.

In Parakh (1960), Bimal Roy’s perceptive satire on how greed affects human behaviour, Rashid plays one of the five prominent persons in the village, a doctor by the name of Hari, ‘who only treats those who can pay him’. Bimal Roy won yet another Filmfare Award for Best Director for the film and Rashid excelled as Hari.

In Parakh (1960), Bimal Roy’s perceptive satire on how greed affects human behaviour, Rashid plays one of the five prominent persons in the village, a doctor by the name of Hari, ‘who only treats those who can pay him’. Bimal Roy won yet another Filmfare Award for Best Director for the film and Rashid excelled as Hari.

In Amar Kumar’s Garm Coat (1955), Rashid plays Munnilal, Girdhari’s (Balraj Sahni) co-worker. The scene in which Girdhari is determined to kill himself by jumping in front of a speeding train suspecting his wife Geeta (Nirupa Roy) of infidelity, but is dissuaded by both Munnilal and Sher Khan (Jayant) is amongst the notable scenes in the film. In Moni Bhattacharya’s Usne Kaha Tha (1960), Rashid enacts the role of tonga driver, Khairati Chacha, a friend of Nandu (Sunil Dutt), brilliantly. The film featured the popular song Chalte hee jana, chalte hee jana, composed by Salil Chowdhury which introduced the idyllic beauty of the rural lifestyle through a lively tonga ditty with Rashid directing the cart.

In Raj Khosla’s thriller Bombai Ka Babu (1960), Rashid brings telling conviction to his character of the hookah-gurgling, shrewd-eyed Bhagatji, who intuits that Babu (Dev Anand) is a criminal on the run and threatens to give him away, unless Babu agrees to impersonate the long-lost son of a rich household.

In Raj Khosla’s thriller Bombai Ka Babu (1960), Rashid brings telling conviction to his character of the hookah-gurgling, shrewd-eyed Bhagatji, who intuits that Babu (Dev Anand) is a criminal on the run and threatens to give him away, unless Babu agrees to impersonate the long-lost son of a rich household.

A late starter (Rashid was already thirty-one years old when Dharti Ke Lal released in 1946), he did reasonably well in the career that followed. Supremely at ease with himself, Rashid was content with whatever came his way and never went looking for work. ‘I am a mean artiste. I sell my talent only to the buyer who comes looking for it. “Chana jor garam ki awaaz nahi lagata.”' (I don’t go around asking for work). A versatile actor, he was as much at ease with comic roles as he was with playing negative shades, which the audience loved. The skinny man with a heavyweight name, Akhara Singh in Bhappi Sonie’s Ek Phool Char Kante (1960). Rashid, the doctor’s assistant in Akhtar Mirza’s Mohabbat Isko Kahate Hain (1965). Hanuman Singh in Lekh Tandon’s Professor (1962). Baakht Buland in Akhtar Husain’s Pyar Ki Baten (1951). Dharamdas, the moneylender in Bimal Roy Pictures’ Do Dooni Chaar (1968). Raddiwala Kaka in Raj Kapoor’s Shree 420 (1955). Pannu in Akhtar Husain’s Darogaji (1949). Again a doctor in Zia Sarhadi’s Hum Log and Kidar Sharma’s Bedardi (both 1951). Rashid Khan left a mark in all of these roles.

‘Considering my short appearance, you can call me a beardless goat but in reality, I am like an elephant of the popular fable where six blind men touch an elephant for the first time, and each creates his own version of how the elephant looks.'

Rashid used his nondescript appearance to his advantage and never allowed himself to get typecast. He once explained his versatility with characteristic humour: ‘Considering my short appearance, you can call me a beardless goat but in reality, I am like an elephant of the popular fable where six blind men touch an elephant for the first time, and each creates his own version of how the elephant looks. In my case, four blind men met me and each one of them formed his own opinion of my abilities. In Dharti Ke Lal and Nau Do Gyarah I was asked to play a sympathetic character, in Bombai Ka Babu, a hard-core villain, and a comedian in Ek Phool Char Kante.’ When asked if he prefers to play comic roles, Rashid responded, ‘Actors should not get labelled in any way or typecast. I am like a monkey who dances to the tune of the “madari” (juggler). It is up to the madari what tune he wants me to dance on.’

Very little is known about his family and family life.

The illustrious occupant of 132 Cadell Road in Mahim passed away in 1972. Having created a niche for himself in a difficult industry, Rashid Khan is one of many who deserve a respectable place in the history of Indian cinema.

Filmography of Rashid Khan

Between 1946 and 1972, Rashid Khan acted in 85 films (there may be more waiting to be discovered). These are: Dharti Ke Lal (1946), Anjuman (1948), Darogaji(1949), Afsar (1950), Baazi, Hum Log, Nadan, Sabz Bagh, Pyar Ki Baten, Bedardi (all 1951), Sheesha, Jaal (both, 1952), Aah (1953) Aar-Paar, Munna, Taxi Driver (all, 1954), Shree 420, House No. 44 (1955), Garm Coat, Yasmin,Joru Ka Bhai (all, 1955), Chori Chori, Heer, Sailaab, Jagte Raho (all, 1956), Musafir, Sheroo, Nau Do Gyarah, Lal Batti (all, 1957), Adalat, Lajwanti, Kala Pani (all, 1958) Char Dil Char Rahen, Heera Moti (both, 1959), Kala Bazar, Ek Phool Char Kante, Bombai Ka Babu, Usne Kaha Tha, Parakh, Anuradha, Mehlon Ke Khwab, Apna Haath Jagannath (all, 1960). Hum Dono, Mem Didi (both, 1961) Professor, China Town (both, 1962). Bluff Master, Shehar Aur Sapna, Tere Ghar Ke Samne, Mujhe Jeene Do (all, 1963), Sanjh Aur Savera (1964), Guide, Akash Deep, Bahu Beti, Mohabbat Isko Kahete Hain, Faraar, Ek Sapera Ek Lutera, Aasman Mahal, Teen Devian (all, 1965), Teesri Manzil (1966), Palki, Duniya Nachegi, Jaal (all, 1967), Duniya, Do Dooni Chaar, Kahin Aur Chal (all, 1968), Prince, Badi Didi (both, 1969), Aan Milo Sajna, Sachaa Jhutha, Bhai Bhai (all, 1970), Gambler, Elaan, Sharmeelee, Do Boond Pani, Kal Aaj Aur Kal, Pyar Ki Kahani (all, 1971), Annadata, Anokha Daan, Mome Ki Gudiya, Ek Nazar (all, 1972), Banarasi Babu, Chhupa Rustam (both, 1973) Dil Diwana (1974).

Note: Effort has been made to authenticate the filmography, credit given to Rashid Khan in a few could not be verified in the films not available in public domain.

Note: Effort has been made to authenticate the filmography, credit given to Rashid Khan in a few could not be verified in the films not available in public domain.

525 views

.jpg)