Warning: what follows is not an objective appraisal of an actor’s career; it is a paean.

I’m wrapping up my romance with Bollywood in a gauze of rose-coloured memories and putting it away with other precious keepsakes: Rishi Kapoor is gone. He was my gateway drug, the reason I fell in love with Hindi cinema in the first place, when as a 7-year-old I watched Doosra Aadmi on an illegally-acquired VHS tape in Lahore. (Illegal because there was a ban on Indian films in place in Pakistan since 1965; a ban we got around by birthing a gargantuan video rental culture around tapes smuggled in via Hong Kong, Dubai et al). When he sauntered down a hilly road in top-to-bottom denims, with Kishore Kumar as his voice, and an otherworldly mist playing hide-and-seek around him, I felt how Rakhee’s character felt watching him.

I’m wrapping up my romance with Bollywood in a gauze of rose-coloured memories and putting it away with other precious keepsakes: Rishi Kapoor is gone.

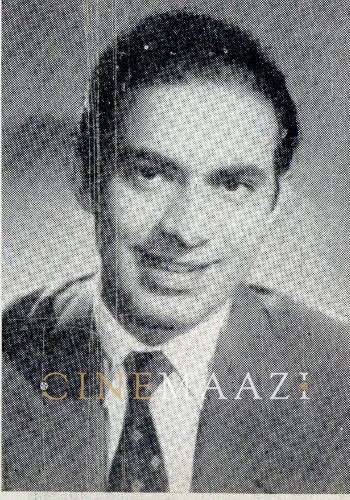

He may have been the original chocolate hero but it was chocolate laced with a high-end liqueur, like the naughty little boy next door grown up into a cocky, charming man with tricks up his sleeve and seductive secrets to tell. His physicality was the embodiment of the concept of the feminised male fantasy figure: a masculine man whose aura nonetheless has a feminine familiarity and tenderness, unthreatening but deeply erotic. He wasn’t ruggedly handsome, like, say,

Vinod Khanna; he wasn’t even handsome, in fact. He was beautiful. The camera adored his face more than it did many of his heroines’; his porcelain complexion, tousled mop of hair, flirtatious gaze, and that playful, disarming smile, were the stuff of many a teenage fever dream in the 1970’s, when he was at the initial peak of his eventual 50-year cinematic career.

His physicality was the embodiment of the concept of the feminised male fantasy figure: a masculine man whose aura nonetheless has a feminine familiarity and tenderness, unthreatening but deeply erotic.

But if he were only looks and attitude that career streak could never have lasted as long as it did. He was naturally gifted as an actor in the traditional, presentational style that was the hallmark of Hindi cinema, able to glide from drama to comedy with deceptive, enviable ease. One need only to look to the character arc he creates in

Karz as Monty/Ravi Verma, arguably his most iconic role (in, ironically, a film that was initially a box-office dud, but today considered a monster cult classic). He segues from the early light-hearted segments to the dark torment of remembering his tragic past life with not a single false note in sight, making the high-concept plot not only believable but also emotionally compelling.

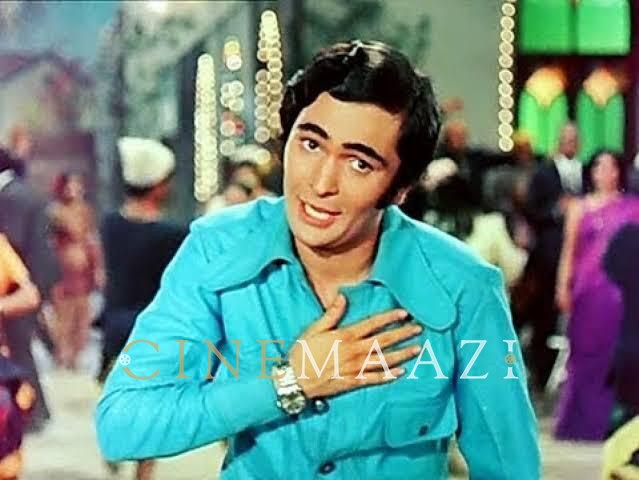

Rishi had a natural sense of rhythm but also brought a supremely confident swagger to his moves that elevated the simplicity of the steps to something more complex and sophisticated

He was also electrifying in his dance numbers at a time when filmi choreography required not necessarily technical skill or precision, but an innate understanding of how the camera translates movement and expression to the big screen. Rishi had a natural sense of rhythm but also brought a supremely confident swagger to his moves that elevated the simplicity of the steps to something more complex and sophisticated (think ‘

Kaho Kaise Rasta Bhool Paday’ from

Bade Dilwala, or the Medley from

Hum Kissise Kam Nahin). In addition, he possessed a singular, instinctive ability to use gestures to convey the emotion and essence of the lyrics. His three iconic

qawwalis – from

Hum Kissise Kam Nahin,

Amar Akbar Anthony, and

Zamane Ko Dikhana Hai (ZKDH) – ably demonstrate this command over the song sequence, including his unmatched ability to lip-synch in perfect unison with the vocal track. In all three, he is seated for the majority of the song (as

qawwals traditionally are) so has to rely almost entirely on his mannerisms and body language to keep us engaged and capture the energy of the music. He does so with panache. Other actors have great songs in their filmic oeuvre but Rishi is the one whose songs are nigh impossible to hear without picturing him and his performance. Just try it: can you think of ‘

Ek Main Aur Ek Tu’ (

Khel Khel Mein) without simultaneously seeing a young, curly-haired Rishi exhuberantly bopping his head to that infectious beat? Or can you listen to the audio of ‘

Dil Mein Jo Mere Sama Gayi’ (

Jhoota Kahin Ka) without picturing Rishi and his Pinto’s Garage cohorts in their denim jumpsuits dancing up a storm? Are you able to hear ‘

Meri Umar Ke Naujawano’ (

Karz) without imagining a giant turntable with Rishi atop it, pulling off a dazzling silver-sequined outfit with the artlessness that was his specialty?

These film choices, along with 1989’s Chandni and 1993’s Damini, are also illustrative of Rishi’s willingness and enthusiasm for being part of what were often patronisingly referred to as ‘heroine-oriented’ films. The term may sound cringe-worthy to some today, but the fact is that many of those projects were gigantic hits precisely because audiences expected woman-centric films to have emotionally-charged, compelling stories, big performances and dhamaakay-dar dialogues.

He was one of the precious few who were able to sustain a largely steady career in the face of the Bachchan Angry Young Man action film onslaught (and also, savvily, insinuated himself into the frothier, ‘palate cleanser’ angle of the narrative in a number of Big B starrers). There were troughs, to be sure, when big films like

Saagar,

Yeh Vaada Raha, and the aforementioned

Karz and

ZKDH didn’t attract big numbers, but there was always a respite waiting in the wings to offset the financial failures. When

ZKDH and

Yeh Vaada Raha faltered,

Prem Rog came along; when

Saagar and

Duniya collapsed, it was

Tawaif and

Nagina to the rescue. These film choices, along with 1989’s

Chandni and 1993’s

Damini, are also illustrative of Rishi’s willingness and enthusiasm for being part of what were often patronisingly referred to as ‘heroine-oriented’ films. The term may sound cringe-worthy to some today, but the fact is that many of those projects were gigantic hits precisely because audiences expected woman-centric films to have emotionally-charged, compelling stories, big performances and dhamaakay-dar dialogues. A number of big (and not so big) stars let their egos get in the way and wouldn’t touch this lot of films, while Rishi played smart and won critical appreciation, and cleaned up at both bank and box-office. On a related note, in films like

Damini and the otherwise revolting

Naseeb Apna Apna (1986), he played almost irredeemably unlikable men doing highly questionable if not completely awful things, with great conviction, at a time when even much more vaunted anti-heroes of Hindi cinema never strayed too far from being sympathetic.

It’s probably important to also address Rishi Kapoor’s so-called 2nd innings, for those of you who might be part of his millennial audience, or even younger, and therefore more familiar with his more recent work. I say so-called because, well, for so many of us Rishi never actually went anywhere, he was always around, perhaps not in the centre of the spotlight but never completely in the dark either. At least half a dozen times over the last forty years or so he was written off as irrelevant or a has-been, but every time just when we thought he was out, he would pull his way back in, donning a slightly modified avatar each time. So for his true blue admirers, yes, it was immensely gratifying to see the final, dazzling surge when he headlined New Bollywood’s prestige projects and became a draw for an entirely new generation of young fans. It was great to see him team up again with Amitabh Bachchan (

102 Not Out), take the edge off the stigma of playing a gay man (Student of the Year), tackle the issues of the new urban middle-class (

Do Dooni Chaar), essay a raunchy nonagenarian (

Kapoor & Sons), take up cudgels against religious bigotry (

Mulk), and bite with gleeful relish into outright villainy (

Agneepath and

D-Day). It was especially moving to witness him share the screen with his son Ranbir (who has inherited a good chunk of his father’s old-world charm and natural ease in front of the camera), and his wife Neetu Singh, in

Besharam.

But even without these last hurrahs, for me and countless others, Rishi Kapoor will still always be matchless, a one of a kind star-actor who brought an added spark to the films that were worthy of his presence

But even without these last hurrahs, for me and countless others, Rishi Kapoor will still always be matchless, a one of a kind star-actor who brought an added spark to the films that were worthy of his presence, and elevated the ones that weren’t, on the strength of his talent, his magnetism, and his boundless commitment to his art. And as I watch him walk away and disappear into that mist again, I give thanks to the gods of cinema for letting me live, and love, in the time of Rishi Kapoor.

Ab to yeh jeena tere bin hai saza…

.jpg)