Haunted Havelis, Thieves, and Auto Wallahs: Bollywood checks into the Hitchcock Motel

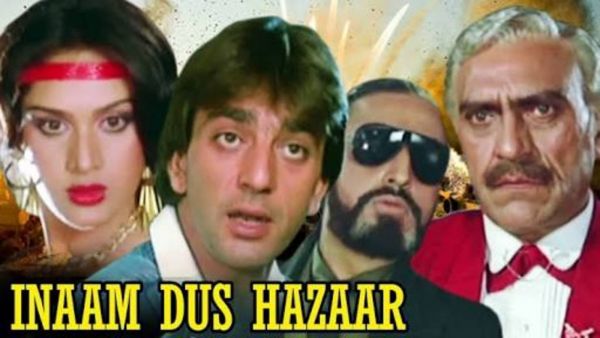

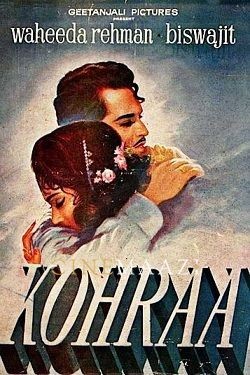

Hollywood directors like Quentin Tarantino, Roman Polanski and Francis Ford Coppola have often made appearances in Indian cinema—with films like Kaante (Sanjay Gupta, 2002), Manorama Six Feet Under (Navdeep Singh, 2007) and Sarkar (Ram Gopal Verma, 2005) respectively—but the one popular filmmaker from Hollywood with a sustained influence on Indian cinema, from the 1960s onwards, has been Alfred Hitchcock. With their clever mix of murder, suspense and romance themes, Hitchcock’s films have been smoothly adapted in a number of Indian films. With films like Saavi (Karthik Raghunath, 1985) in Tamil, Hitchcock easily transitioned from a mainstay in Hindi-language films to other genres and languages as well. A few notable examples include Biren Nag’s adaptation of Rebecca (1940) with Kohraa (1964), The 39 Steps (1935) made into Basu Chatterjee’s Chakravyuha (1978), Vijay Anand’s Jewel Thief (1967), inspired by the universe that To Catch a Thief (1955) operated within and the Sanjay Dutt-Meenakshi Seshadri starrer Inaam Dus Hazaar (Jyotin Goel, 1987), a fun-filled take on North By Northwest (1959). Hitchcock left his traces markedly in Raj Khosla’s work in the 1960s, with Woh Kaun Thi? (1964), Mera Saaya (1966) and Anita (1967)—haunting music, foggy landscapes, femme fatales, and claustrophobic close-up shots of Sadhana in these films closely followed what an international audience would have recognized as trademark Hitchcock fare. Two decades later, Vidhu Vinod Chopra paid cinematic tribute to Psycho (1960), intercutting shots from the film’s iconic shower scene playing on the television with audio of a character’s murder in the shower in Khamosh (1985). What is it, then, that makes Hitchcock so adaptable to the templates of Indian cinema?

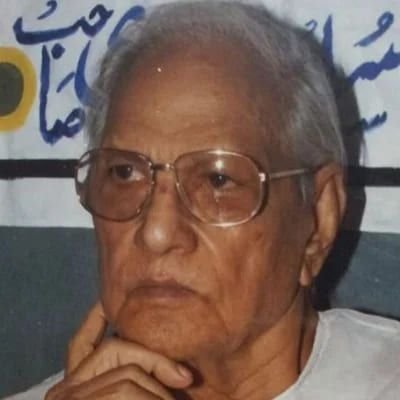

Though it was a box office failure, Kohraa had an impressive cast: Waheeda Rehman, already a star, Biswajit, dubbed the ‘suspense hero from Bengal’, and Lalita Pawar, the go-to actor for female villains. Much of the strength of the film, even in the original, relied on the acting prowess of the two women. Waheeda Rehman as the spirited Rajeshwari and Lalita Pawar as Dai Maa played their roles to perfection, granting the film its moderate success. G.L. Jadhav and T.K. Desai’s art direction skillfully replicated the majestic sweep of Manderley with miniatures for the outside views of Mayfair, and opulently decorated interiors for the rest of the film. The combination of the two leaves the viewer guessing, as Hitchcock does. We never really have a complete sense of the unending house, even as the walls and ceilings seem to close in on the characters in their oppressive glamour. Marshall Braganza’s technical expertise with the camera added to the mix, using light and shade to its best advantage. Biswajit in an interview recalls how he followed the actors in a car with the camera mounted upside down to get the perfect shot. Taking off from Hitchcock’s use of silence followed by sudden sound, Nag amped up the melodrama in the film with a skillful use of sudden background music. Lilting melodies populate the film with a hint of the tragic, best exemplified in Yeh Nayan Dare Dare, sung by Hemant Kumar and penned by Kaifi Azmi. In Kohraa, Rebecca’s costume design undergoes a subtle change. While Biswajit’s Raja Amit Singh is dressed incredibly like Max de Winter, down to the pencil-thin moustache, Dai Maa is dressed either in all-white or all-black, indicating the ambivalence of her character. Hitchcock’s narrator dons dark colours only after the mystery is revealed, but the more spirited Rajeshwari is dressed in a number of colours. The all white costume with a profusion of veils is reserved for the dead Poonam. By the last half hour, Poonam’s clothes have taken on a life of their own, and become the ghost that haunts Raj.

.jpeg)

Despite these innovations in adaptation, Kohraa’s greatest strength also becomes its greatest weakness. The feudal setting, crumbling wealth slipping out of the hands of a wealthy manor owner with a dark secret, all of these seem ingredients for a winning formula of horror (Dracula, anyone?). However, Nag’s film does not take this decline to its logical conclusion. Unlike Manderley, which burns to the ground, Mayfair is left standing at the end of the story. Ultimately, the narrative’s obsession with inheritance and property lands the faithful servant in the docks. It is true that Kohraa attempts to reflect on the decline of powerful zamindar families in Bengal, and their increasing obsolescence by the 1960s. However, stuck somewhere between a supernatural thriller and a whodunit, the film is unable to commit fully to its project of depicting feudal ruin, and the unsettling of power upheld throughout the film ends in a peaceful resolution that exonerates both Amit and his faithful wife, now capable of helping him administer his large estate.

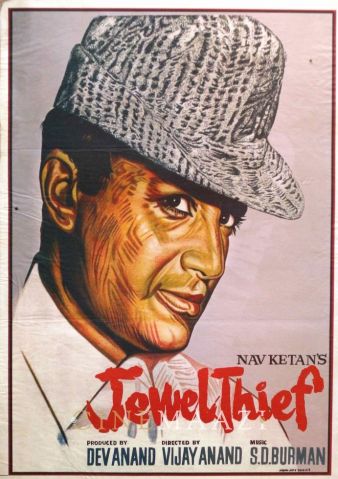

Made only three years later, Vijay Anand’s Jewel Thief is vastly different in tone. For one, it is a world of colour, and one that has been opened up to the global and the urban. Set in the roaring ‘60s, Jewel Thief combines elements of To Catch a Thief, North by Northwest, The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) and Vertigo (1958) and employs to the hilt the classic Hitchcockian convention of the “wrong man thriller”. Taking off from the mis/recognition melodrama that provides the backbone to thrillers like Kohraa, Jewel Thief introduces a smooth, suave, fast-talking hero with an equal capacity for romance and comedy. Like Cary Grant in To Catch a Thief, Dev Anand’s Vinay is equipped with only his wits (and his dashing costume) when he is drawn into a game of doubles, shadowing himself through Delhi and the ‘exotic’ Gangtok. In a scene that adapts with panache James Stewart’s breakdown in Vertigo, Vinay suffers a seeming breakdown, aided by the machinations of a criminal mastermind, but emerges victorious at the end, which keeps with the rules of popular Hindi cinema. Bolstered by the rogue persona he had taken on in earlier films like Baazi (1951) and Jaal (1952), Dev Anand slips into Cary Grant’s shoes with ease. His clothing, his scarf, and his swagger—head cocked to the side, a cigarette dangling from his lips—closely mimics that of Grant’s in To Catch a Thief. Like Grant’s Robie, he is constantly watched, with gazes replicating across the film even as the camera lovingly follows him. In a comedic imitation of Robie’s suave seduction of Grace Kelly’s Frances Stevens in the film, Dev Anand’s Vinay enhances the metaphor of bait, walking in the path of Tanuja’s car with a fishing line dangling a white plastic fish.

Jewel Thief deftly fits into the spectacle of a new world of conspicuous consumption, repeating Hitchcock’s opening with shop windows displaying jewels placed on women’s busts, successively nabbed by a quick-fingered thief. Desire multiplies on the screen, melding jewels and women’s bodies into the same surface, even as the film maintains the deceptively glamorous world both imply, subverting the very notion of the real. Tanuja as Anjali hints at a chic Western culture of modern love where the woman is unafraid to assert her desires, while Vyjayanthimala’s Shalini sustains the codes of Hindi melodrama. Shalini and Vinay’s relationship plays to the Indian audience’s expectations, starting with her dressed as the forsaken lover in all white in Rula ke gaya sapna (sung by Lata Mangeshkar with lyrics by Shailendra and S.D. Burman’s music). Shalu and Vinay’s story unfolds ensconced in nature, drawing upon the trope of the hill station as a picturesque space for romance in Hindi cinema. The ingenuity of the film lies in that it never loses itself to the traditional melodrama that provides its roadmap, bringing in a suspenseful plot with all the right ingredients—a dastardly criminal gang, comic interludes, action, and a generous dash of romance. Grace Kelly’s sexually ambitious moves are distributed between the two women, ascribing to Tanuja her direct advances towards the hero, and keeping the duplicitous Shalu sacrosanct by way of her need to protect her brother.

.jpg)