Epidemics and Indian Cinema: A Story of an Enigmatic Film

Arrival of motion pictures in India (1896) and the plague epidemic

Incidentally, the very first arrival and the projection of the motion pictures in Bombay / Mumbai on 7 July 1896 had nearly coincided with the bubonic plague epidemic. When on that rainy day of July, Lumiere Brothers’ representative Marius Sestier had presented the three-in-one Cinematographe (camera, projector, and printer) at Bombay’s Watson’s Hotel (building still extant), the potential bubonic plague pandemic was round the corner. By September 1896, it went on to attack the city ferociously, and soon, 20,000 people had fled it; the city’s population had halved to 450,000 people from 846,000. The 1896 plague pandemic is said to have lasted for thirty long years, by which time Dadasaheb Phalke had already made his first silent feature film Raja Harishchandra (1913). About the 1896 Bombay Plague, as it is still known as, though we find some reports and photographs in print media, no motion pictures on or about it could be traced.

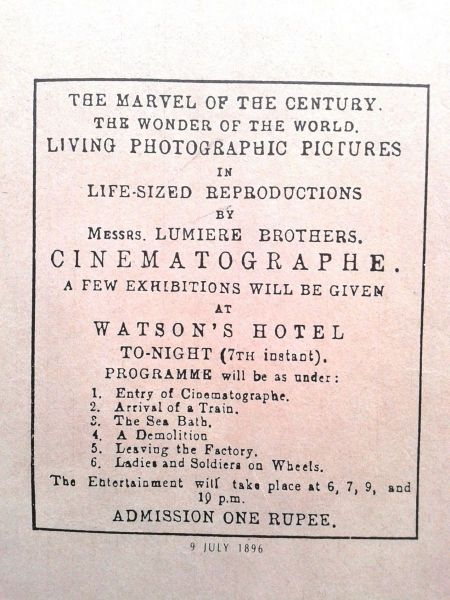

In a Watson’s Hotel room, on that evening of July, Mr. Sestier had shown six short ‘living photographic pictures in life-sized reproductions’ by Messrs Lumiere Brothers made in France on their Cinematographe. The Mumbai shows were repeated, and one of the advertisements published in the Times of India of 9th July 1896, had announced the following programme:

The Plague Epidemic / Pandemic

It was the third major plague pandemic that had begun in Yunnan, China in 1855 and spread to all inhabited continents, ultimately leading to over 12 million deaths in British India and China, with about 10 million killed in India alone. The initial outbreak affected Bombay but soon spread further to Poona (Pune) and Karachi, reaching Calcutta / Kolkata the following year. Colonial government actions to control and treat the plague outbreak were extensive, but generally ineffective and harsh in the first stages. A campaign of quarantines, isolation camps, travel restrictions, demolition and disinfection of buildings was pursued, leading to massive resistance which forced colonial authorities to revise their epidemic control policy. Several international plague commissions operated in India in the first years of the epidemic, including commissions from Russia, Austria, Germany, Italy and the Institute Pasteur. The latter made a major contribution through Paul-Louis Simond’s discovery of the implication of the rat’s flea in the transmission and spread of the disease. The photographic record of the outbreak in India is international and covers a range of topics, including anti-plague measures, clinical symptoms, and the depiction of plague hospitals. (Centre for Research in the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, the University of Cambridge)

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the pandemic had remained active for over three decades, and by around 1960, the worldwide casualties had dropped to a negligible number. In my text here, the words epidemic, endemic and pandemic might get overlapped but the idea is to find a parallel timeline between such calamities and the growth of cinema in India and see whether they have been comprehended in some way by this popular medium right from its birth.

Plague and the Marathi film 22nd June 1897

In 1979, this plague epidemic became the context for a Marathi film 22nd June 1897 directed by Jayoo and Nachiket Patwardhan. The film, while woven around the bubonic plague raging in Poona / Pune (148 km from Bombay) narrates the story of the Chapekar Brothers (Damodar and Balkrishna) who assassinated the merciless British officer Charles Walter Rand, Assistant Collector of Pune and Chairman of the Special Plague Committee, Pune and British Army Officer Lieutenant Charles Egerton Ayerst. The date of assassination was 22nd June 1897.

Directed by Devandar Kumar Pandey, Chapekar Brothers was yet another film in Hindi released in 2016. However, this film differs in its emphasis and angle from that of 22nd June 1897 which encompasses a larger historical perspective beyond a biopic.

Leprosy and a Marathi film

The Marathi film, Dr. Prakash Baba Amte: The Real Hero (2014), though a biopic of the lives of Dr Prakash Baba Amte and his wife Mandakini, it cannot escape the history of the place. Baba Amte (Murlidhar Devidas Amte, 1914-2008) had established an ashram called Anandwan way back in 1948 largely influenced by Mahatma Gandhi. Situated in the Chandrapur district of Maharashtra, the ashram shows the remarkable work embarked upon by Baba Amte towards rehabilitation and empowerment of people suffering from leprosy. Baba Amte’s contribution towards fighting leprosy in India to dispel the social stigma that leprosy was a highly contagious disease has now been known internationally. Baba Amte and his wife Sadhanatai Amte started out with no resources to fight leprosy in India and provide a home for the miserable patients.

The Leprosy Epidemic

Leprosy as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), the body very much in the news during the present Covid-19 times, is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae; it is also known as Hansen’s disease. The disease mainly affects the skin, peripheral nerves, mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract and the eyes. Leprosy is known to occur at all ages ranging from early infancy to very old age. Leprosy is curable and early treatment averts most disabilities. Leprosy is one of the oldest diseases which are evidently described in the literature of ancient civilizations. Even though the field of medical science has made many advances in recent times, leprosy remains a heinous cause of death. Historically, leprosy has affected people since at least 600 BC. Worldwide, two to three million people are estimated to be permanently disabled because of leprosy. India has the greatest number of cases, with Brazil second and Indonesia third. As reported by WHO through its data collected from 115 countries and territories in 2006, and published in the Weekly Epidemiological Record, the global registered prevalence of leprosy at the beginning of the year was 219, 826 cases.

The film Dr. Prakash Baba Amte: The Real Hero directed by Samruddhi Porey and starring Nana Patekar, Sonali Kulkarni and Mohan Agashe carries a definite echo of the Anandwan established by Baba Amte, and it does provide us a reference point to some extent in this realm.

Jaundice and a Bengali film

Satyajit Ray’s 1990 film Ganashatru encapsulates a story of contaminated water turned holy water at a temple, consumption of which causes jaundice among gullible devotees. This Bengali film by the maestro is an adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People which, in its plot has a spa that has contaminated water with poisonous bacteria. Dr. Thomas Stockmann, its medical officer, detects it and would like to make it public by publishing an article in a local newspaper. His brother, who is the Mayor of the town, would not like it to happen. The news could lead to a big public outcry and the shutdown of all baths, resulting in serious revenue loss to the public exchequer. The dramatic tension arises between the idealistic truth and the pragmatic practicality, no matter fatal. In its adaptation, Ray, very ingeniously transforms the spa into a temple. He is also more specific about the nature of the diseases, e.g. jaundice / hepatitis epidemic and superstition about the nature of the diseases (e.g. jaundice) the contaminated water could cause, unlike Ibsen’s play, which remains general in this realm. The Norwegian play was written in 1882, 108 years prior to Ray’s film Ganashatru.

Dr. Ashok Gupta, played by Soumitra Chatterjee, an honest doctor, diagnoses the alarming spread of jaundice among his patients. To identify the cause, he analyses the water of a populated part of his town Chandipur. According to the laboratory reports, the holy water (charanamrita) of the Tripureshwar temple, a famous temple and tourist attraction of the town, is found to be contaminated due to damage to the underground piping system. This contaminated holy water is consumed by hundreds of devotees. The temple was the source of income for all the corrupt politicians (and other vested interests). Among these politicians is Dr. Gupta’s younger brother, Nishith Gupta (Dhritiman Chaterji), who is also the Chairman of the Municipality. He and other beneficiaries of the temple decide to prevent the doctor from alerting the people by getting the news published in a local newspaper.

While with his family at home, Dr Gupta announces his resolve to fight against authorities to stop people from consuming contaminated water –

People jostle to get the holy water at the temple –

Jaundice Epidemic: Global Impact

Inflammation of the liver is usually referred to as hepatitis. Viral hepatitis is a widespread infectious disease normally caused by the hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D and E. The condition can be self-limiting or can progress to liver fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis or liver cancer. In India, as per the latest estimates, 40 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B and six to 12 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C. HEV is the most important cause of epidemic hepatitis, though HAV (Hepatitis A Virus) is more common among children. Most acute liver failures diagnosed are attributable to HEV (Hepatitis E Virus). (World Hepatitis Day 2017 Report). This is just to broadly indicate the nature and extent of the jaundice or hepatitis disease scaling the levels of an epidemic.

This shows the concerns and anxieties of Henrik Ibsen’s Dr. Stockmann (An Enemy of the People) and Satyajit Ray’s Dr. Ashok Gupta (Ganashatru).

A strange story of a film made nearly a century ago…

Though narrated in the times of the Covid-19, these are fairly recent stories of pictures and the pandemics, you might be curious to know as to what had happened nearly a century ago in the history of Indian cinema? What was the epidemic then?

Cholera and the silent film (1923)

This strange 1923 silent film still extant in Dublin’s Irish Film Archive was made by an Irish missionary and it was titled The Catechist of Kil-Arni. As per the titles in the beginning of the film, it was produced by Reverend T. Gavan Duffy for Pondicherry Mission, India. Soon after the title, we see him busy typing and the title of the film appears. This was perhaps the first film in India that had dealt with an epidemic – in this case cholera.

Before I begin to narrate the story of the film and its making, you can see how the film The Catechist of Kil-Arni launches itself.

The Making of The Catechist of Kil-Arni: The Story of Rev. T. Gavan Duffy

Thomas Gavan Duffy, Irish by parentage, was a missionary in India from 1911 until his death in 1941. He arrived in Pondicherry in December 1911 and then he was appointed as assistant parish priest at Chetpet in North Arcot District. After having visited many villages in Tamil Nadu, he decided to establish his missionary centre at Tindivanam and established several educational institutions for the local poor untouchables.

Paying rich tribute to him on the 125th birth anniversary of Rev. Thomas Gavan Duffy (25 September 1867, Dublin, Ireland – 4 August 1932, Tamil Nadu, India), A. Chinnappan described him as the ‘morning star for the people, a great thinker, philosopher, motivator and liberator.’ (The New Leader, 16-28 February 2014, published from Chennai). Gavan Duffy, as Fiona Bateman writes in her well-researched and studied paper An Irish Missionary in India: Thomas Gavan Duffy and the Catechist of Kil-Arni, joined a French missionary order, the Paris Foreign Mission Society which, in September 1911, ordained him and appointed him to the Pondicherry mission in South India, where he spent most of the remainder of his life.[Fiona Bateman, in: Tadhg Foley, Maureen O’Connor (Eds.), Ireland and India: Colonies, Culture and Empire, Dublin: Irish Academic Press.] The book covers the presentations made at the Fourth Galway Conference on Colonialism, "India and Ireland", held at the National University of Ireland, June 2004.

The Church was aware of the power that the audio-visual medium possessed for the purpose of education and propaganda. Rev. Thomas Gavan Duffy, already known for his great amount of writings on many mission-related topics, knew the nitty-gritty of putting up film production gears together, on a fairly more professional scale. Gavan Duffy’s father was a famous Irish nationalist, who had been a Young Ireland activist and editor of the Nation, and became Prime Minister of Victoria, Australia, before retiring to France. As Bateman writes, Gavan Duffy established the audiovisual unit at Tindivanam, probably the oldest one in Catholic India. Tindivanam is a town and municipality in Villupuram district in Tamil Nadu. The clergy in Ireland became quite adept at the new motion picture technology. Many missionary orders produced their own films to be shown in schools and public venues. In India, particularly, when illiteracy (inability to read or write) prevailed on a massive scale the medium of film was very effective for education, entertainment and propaganda purposes.

As the film The Catechist of Kil-Arni demonstrates, Thomas Gavan Duffy does an accomplished job as a story-teller mixing fiction and nonfiction methods of casting and filming. By 1923 when this film was released, Indian cinema had already become a decade older after Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra and during this time it had explored several subjects beyond just mythological ones. In 1923 alone over 50 silent films were produced in India. Obviously, Gavan Duffy’s film was a part of the campaign to promote the idea of the catechist.

The Catechist of Kil-Arni: The Story

The catechist in the film is a thief named Ram, who, following his imprisonment during a cholera epidemic, which has snatched away his wife Sita’s life, is left alone with his four children. The children are shifted to Catholic orphanages and converted to Catholicism. Ram is also taken into the fold and made a catechist. The intertitle explains, “the story of how the potter Ram, who was a pagan and a thief living in the Indian village of Chetpet, became the Catechist Joseph, still rough, but now thoroughly good.” The narrative, which is basically a fictional tale of conversion and redemption, includes elements of anthropological interest.

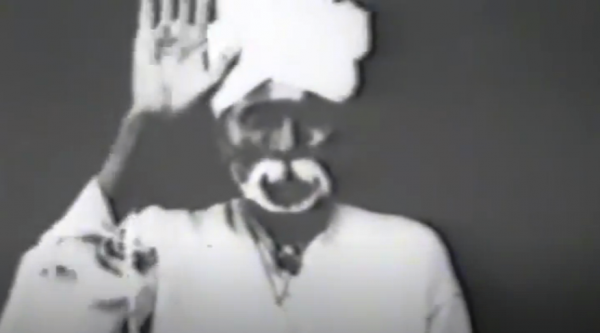

Ram, the thief-turned-catechist as he appears in the film –

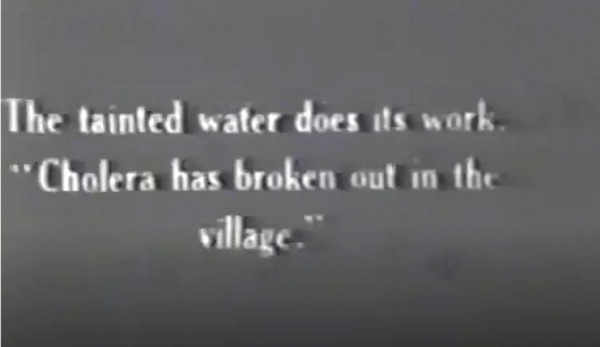

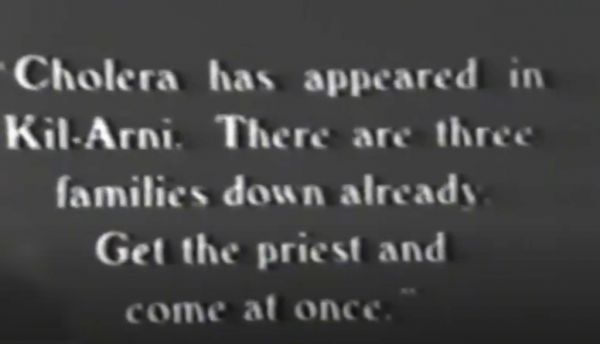

The tainted or contaminated water appears again as if it was the precursor to the Norwegian Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People (1862) and Satyajit Ray’s Bengali film Ganashatru (1990). Back to 1923 and an intertitle –

The news leads to immediate panic among the village inhabitants and they begin to run helter-skelter. Scared, they resort to various ritualistic performances to shoo away the disease like polytheistic pagans. And the intertitle explains: “A suckling pig is buried alive, and some of pagan villagers come and jump over the emerging head hoping by this superstition to escape disease!” Amidst all this, many people keep deserting their village. Ram also prepares to leave but then changes his mind because – The village will be empty, giving him a chance to get rich quickly by looting the abandoned huts!

Amidst the appearance of the cholera epidemic, there are also families that would invite the priest for help, and

The silent film The Catechist of Kil-Arni weaves the cholera story quite skillfully to drive the proselytizing propaganda home.

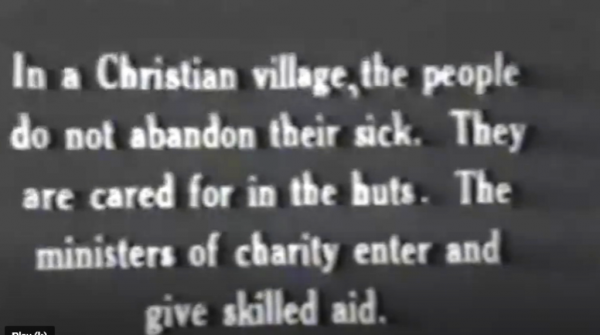

Also through humanitarian services and charity, the clergy (Christian nuns and monks), villagers are served and many are cured of the disease, children given shelter in the orphanages. Roguish Ram gets transformed into a good catechist; he is also enabled to get his daughter married well. There is a celebratory procession with elephants and revelry.

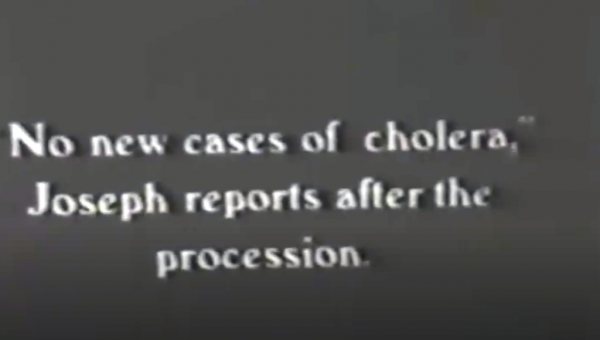

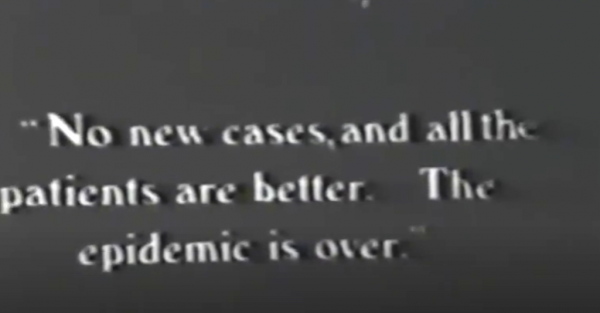

Finally, Joseph the Catechist makes an announcement:

As a story telling device, the film is divided into seven engaging episodes with intermittent intertitles that push the narrative forward – to cheerful, victorious Joseph, the Catechist of Kil-Arni.

Well, my point in this feature is not about critiquing the aesthetics of the film but only to draw attention of Cinemaazi readers to the fact that as early as in 1923, a film had encapsulated a story of an epidemic, in this case – cholera. It could probably be assumed that comparatively this film was much more dynamic and better conceived and constructed than most other Indian silent films till that date.

The First Cholera Pandemic: Some historical glimpses

During the past 200 years, seven cholera pandemics have occurred, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817, there have been many documented cholera outbreaks including 1991-1994 outbreak in South America and more recently the Yemen cholera outbreak lasting from 2016 to 2020. Some claims mention Russia where the first of the seven cholera pandemics had occurred, with one million casualties. Spreading through feces-infected water and food, the bacterium had passed along to British soldiers who brought to India where millions more died. The reach of the British Empire and its navy spread cholera to Spain, Africa, Indonesia, China, Japan, Italy, Germany and America, where it killed 150, 000 people. A vaccine was created in 1885, but the pandemics continued to prevail.

One hundred years later, a mythological silent film in Tamil Nadu…

In 1917, one of the pioneer Tamil filmmakers, Rangaswamy Nataraja Mudaliar, had made the mythological silent film Draupadi Vastrapaharanam adapting an epic Mahabharata story. In Tindivanam, Rev. Thomas Gavan Duffy was over a day’s journey away from Madras (Chennai) where Nataraja Mudaliar was making his films. And in the year Gavan Duffy had made The Catechist of Kil-Arni in 1923, R Nataraja Mudaliar had made yet another mythological Markandeya. Between 1917 and 1923, R. Nataraja Mudaliar had made six silent films. It is interesting to note that some sources attribute the direction of The Catechist of Kil-Arni to yet another silent / Tamil cinema pioneer R.S. Prakash. In her paper, Bateman does mention ‘some professional from Madras’ who were associated with the film. However, as she says, it was Bruce Gordon who had assisted Gavan Duffy on this film, in other words it was T. Gavan Duffy who had directed the film: “In making The Catechist of Kil-Arni, Gavan Duffy was assisted by his friend Bruce Gordon, as well as some film professionals from Madras, including it was rumoured, the distinguished director Raghupati Surya Prakash.” She also affirms that Gavan Duffy doesn’t mention the name of R.S. Prakash. She cites a newsletter produced by Gavan Duffy in which he had recounted the difficulties involved in making the film. Incidentally, in the year 1923 itself, R.S. Prakash had made a silent film titled Gajendra Moksham. Well, this is a separate debate and not pertaining to our topic now.

Epidemics, Endemics, Pandemics and Indian cinema: 1923 – 2019

Virus, a Malayalam film (2019) – The Nipah Virus in Kerala

It is nearly a hundred years’ journey, from the propaganda silent film The Catechist of Kil-Arni (1923) to the Malayalam language medical thriller titled Virus (2019) – it is also a journey from the plague pandemic to coronavirus pandemic via the Nipah virus outbreak in Kerala. The history of Indian cinema is not so comprehensive but the stock-taking exercise is not less exciting. In the film Virus, a man named Zakariya Mohammed is infected and brought to the Government Medical College in Kozhikode, where he suffers from the symptoms of an unknown virus and after a few hours he dies. A nurse Akhila who treated Zakariya gets infected too and slowly more and more cases are detected in surrounding areas. As the death toll rises in number the medical experts identify the virus as Nipah that spreads to many other districts beyond Kozhikode.

Covid-19: A Global Film with 15 Countries’ Participation including India

Still under production, the working title of this global film is The World Beyond Silence. As its Mission Statement mentions, it will be a documentary “between hope and despair, empathy and ignorance, resilience and a feeling that no one can refuse at the moment: the vulnerability of our existence.” It is an interesting project taken up by the Berlin-based Sunday Filmproduktion, whose Project Director is the filmmaker Manuel Fenn (with whom I had an opportunity to work on a documentary film in India). Both he and his wife Antonia (professional editor) will edit each film and make the final cut. Of the fifteen participating countries, India is also one of them.

Cholera to Corona, Bacterium to Virus is a long battle Mankind has fought

From the silent film The Catechist of Kil-Arni to the proposed global film The World Beyond Silence (working title) is a long battle that Mankind has been fighting and documenting, it goes back to centuries – undocumented and yet remembered.

Amen!

Grateful Acknowledgement: My student Jay Kholia for all his help.

Images copyright is with the author.

Tags

About the Author

Amrit Gangar is a Mumbai-based film theorist, curator, historian and author. He writes both in Gujarati and English and has been widely published. Two of his Gujarati books on cinema have won the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi’s awards. He was the Consultant Curator to the National Museum of Indian Cinema, Government of India, located in Mumbai. He has presented his theory of Cinema of Prayoga at various prominent venues in India and abroad, including the Tate Modern, London; the Pompidou Centre, Paris; Lodz Film School, Poland; Santiniketan, India, et al. He was Indian contributor to the Film International published from Tehran, Iran and the bilingual (English / Japanese) ART iT, published from Tokyo, Japan.

Gangar has been the curator of film programs for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Kerala; the Kala Ghoda Artfest, Mumbai; the Mumbai International Festival for Documentary, Short & Animation Films; the Danish Film Institute, Copenhagen, etc. Besides Walter Kaufmann, he has also written books on Franz Osten (Bombay Talkies) and Paul Zils (one of the founders of the still active Indian Documentary Producers’ Association), both film directors from Germany. His book Chalchitra / Chhalchitra has been published by the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi, Gandhinagar. He was also active in Indian film society movement and headed the Mumbai-based film society Screen Unit that has published two major books on Ritwik Ghatak.

Over the years, Gangar has worked on productions of numerous European and Scandinavian films and video installations, including Lars von Trier and Jorgen Leth's Five Obstructions. He is an Adjunct Professor at the IDC-IIT Bombay.

.jpg)