The Legacy of Walter Kaufmann: His Contribution to Hindi Cinema

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Walter Kaufmann was born in a German speaking Jewish Family in Karlsbad, Bohemia (now Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic) on April 1, 1907. Karlsbad was a famous spa city and according to Kaufmann every summer had visitors like Richard Strauss, Bruno Walter, Felix Weingartner, among others. The profound musical environment of Karlsbad with its outstanding symphonies and regular opera performances had a strong influence on the young Walter Kaufmann.

Kaufmann’s parents Julius and Josephine Kaufmann (nee Wagner) lived at Mineralwasser-Versendung in Karlsbad and Walter was born there at House No.1043. According to Kaufmann’s birth certificate, his father was a private official domiciled at Karlsbad. In 1938, his family moved to Bilkova in Prague.

During a very turbulent time in history, Walter Kaufmann had the opportunity to work in the German film industry in Berlin (‘Be-llywood’), and also in the Indian film industry in Bombay (‘Bo-llywood’). Germany‘s biggest film production studios, Universum-Film-Aktiengesellschaft (better known as Ufa), were situated in Babelsberg, Berlin. Bombay housed the maximum number of film studios in India.

By the time Walter Kaufmann arrived at Bombay in 1934, it was an end of the silent film era in India. Though the first sound film Alam Ara was produced by Imperial Film Co. in 1931, silent films continued to be made until 1934. Bombay was a major centre of production and by the end of 1934, talking picture production had reached its peak with 86 companies in Bombay and Maharashtra alone. Thus by 1934-35, Indian talkies had firmly established themselves. However, when Kaufmann arrived in India he found that there was neither a theatre nor an opera house in the European sense of the term. By 1917, the Opera House in Bombay, like many other dramatic theatres, began to show films, catering to the growing popularity of cinema and, in 1925 Pathe’s Cinema rented the whole theatre. From 1929 to 1932, however, Madan’s Theatre leased the Opera House to various Indian theatrical concerns like the Parsi Elphinston Dramatic Company.

.jpeg)

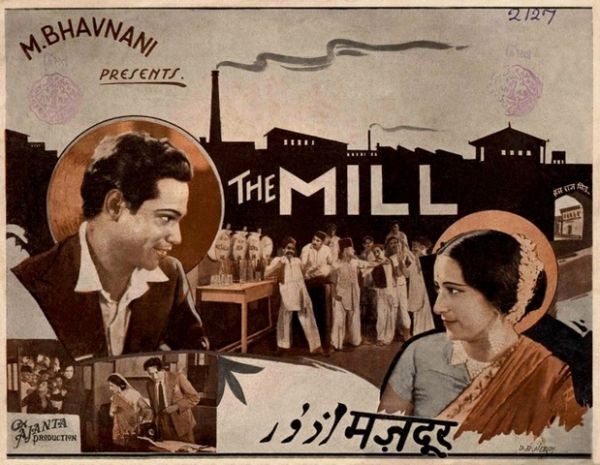

Fairly soon, Kaufmann reconnected with Mohan Bhavnani, about whom he wrote, “He was not particularly successful with the Indian public because he had too much taste. But he was excellent…” Kaufmann composed inter alia the music for Bhavnani’s film The Mill which was banned by the film censors in Bombay and elsewhere. Director-Producer Mohan Dayaram Bhavnani’s films, included Mazdoor (The Mill, 1934), Jagran (The Awakening, 1935), Navjeevan (1935), Jhoothi Sharm (Naked Truth, 1940) and Prem Nagar (City of Love, 1940). Jagran was released in Bombay on 1 January 1936 and Walter Kaufmann is credited as music director of the film along with S.P. Mukerji.

Unfortunately, Bhavnani’s film Mazdoor or The Mill produced in 1934 for which Walter Kaufmann had composed background music had to face censorship problems. In an advertisement, Kaufmann is credited for the film’s ‘orchestration’. (Music was composed by B.S. Hogan).

The President of the Mill Owners’ Association was a member of the censor board in Bombay and tried to get the film banned allegedly for its communist propaganda. The Punjab Board cleared the film initially, but following near-riots after it was released in Lahore, banned it. The Delhi ban was followed by a Central Government Decree that the film had an inflammatory influence on workers.

Anyway, Mohan Bhavnani persisted, and also collaborated with Walter Kaufmann. In 1936, his film Jagran or The Awakening had music composed by Walter Kaufmann in collaboration with S.P. Mukerji. It was actually Bhavnani’s sequel to Premchand scripted Mazdoor /The Mill. Written by Narottam Vyas, an admirer of Premchand, the title evoked the journal Jagran edited by Premchand. Produced independently by Bhavnani, the melodrama about unemployment was shot at the Wadia Movietone Studios, Parel in Bombay. (Later in 1942, Wadia Movietone was bought by V. Shantaram, who started Rajkamal Kalamandir there.) Sometime later, Walter Kaufmann’s friend Willy Haas joined Bhavnani and wrote scripts for his films, including Jhoothi Sharm (Naked Truth) and Prem Nagar (City of Love), both the films were released in 1940.

By 1932 it had become clear to Willy Haas that he would have to leave Germany which was in the grip of Fascist domination. As Anil Bhatti describes, “He returned to Prague in 1933, where he worked as editor and script-writer. After Hitler’s entry into Prague he decided to leave Europe. Although there was the possibility of getting an American visa, he chose instead to accept the offer of his friend Walter Kaufmann, the composer, who was already in India working with the All India Radio in Bombay. Through the mediation of Paul Claudel, Haas was able to go from Prague to the south of France, where he could meet some of his friends from Prague, among them Franz Werfel. He reached Bombay in June 1939, where a post of a scenario-writer with Bhavnani Productions was waiting for him. A film version of Ibsen’s Ghosts, The Legend of The Dead Eyes, which he called an ‘Indian religious village story of my own invention’ and a scenario Kanchan, in which the actress Leela Chitnis played the leading role, were the creative results that Haas mentions.” This information is based on ‘Career of Mr Vilem Haas’ (typed manuscript in the possession of Dr Herta Haas). This document, as Bhatti writes, was apparently required by Haas for his residential formalities in India.

In the field of films, Kaufmann also cooperated with Willy Haas in Bombay. It was most probably for the film called by Willy Haas Dorflegendchen (small legends of the village). Willy Haas wrote the script and Kaufmann composed the music. It is also possible that this refers to the film entitled Indische Legende (Indian legend) the script of which Willy Haas wrote after long studies of Indian village life and of Indian mythology.

.jpg/Ek%20Din%20Ka%20Sultana%20(1)__422x600.jpg)

Though Walter Kaufmann’s notes mention about his composing music for numerous documentary films produced by the Information Films of India (IFI), we do not find the exact information for want of actual source material. However, these films could be only after 1940 since the IFI was started by the Government of India in that year, just after the Second World War had begun.

However Walter Kaufmann spoke on Indian music as also film music. The Department of German at the University of Manitoba (Winnipeg, Canada), for example, wanted him to speak on “Music for Films” during its week long (27 November – 2 December 1955) Festival of the Arts.

Walter Kaufmann died on 8 September 1984 in Bloomington. Constantly struggling with ill health, he did field work, research, wrote, composed, performed, living in exile was not always easy. He has left behind priceless, authentic information and knowledge for India and the world.

Walter Kaufmann was “frightfully good” as a greeting card sent to him said.

This article is an extract from the book The Music that Still Rings at Dawn, Every Dawn: Walter Kaufmann in India, 1934-1946 written by Amrit Gangar and published by Goethe Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan, Mumbai, 2013.

All the images did not appear in the orginal book.

None of the information and/or images in the feature may be reprinted/replicated without the author's permission.

Tags

About the Author

Amrit Gangar is a Mumbai-based film theorist, curator, historian and author. He writes both in Gujarati and English and has been widely published. Two of his Gujarati books on cinema have won the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi’s awards. He was the Consultant Curator to the National Museum of Indian Cinema, Government of India, located in Mumbai. He has presented his theory of Cinema of Prayoga at various prominent venues in India and abroad, including the Tate Modern, London; the Pompidou Centre, Paris; Lodz Film School, Poland; Santiniketan, India, et al. He was Indian contributor to the Film International published from Tehran, Iran and the bilingual (English / Japanese) ART iT, published from Tokyo, Japan.

Gangar has been the curator of film programs for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Kerala; the Kala Ghoda Artfest, Mumbai; the Mumbai International Festival for Documentary, Short & Animation Films; the Danish Film Institute, Copenhagen, etc. Besides Walter Kaufmann, he has also written books on Franz Osten (Bombay Talkies) and Paul Zils (one of the founders of the still active Indian Documentary Producers’ Association), both film directors from Germany. His book Chalchitra / Chhalchitra has been published by the Gujarat Sahitya Akademi, Gandhinagar. He was also active in Indian film society movement and headed the Mumbai-based film society Screen Unit that has published two major books on Ritwik Ghatak.

Over the years, Gangar has worked on productions of numerous European and Scandinavian films and video installations, including Lars von Trier and Jorgen Leth's Five Obstructions. He is an Adjunct Professor at the IDC-IIT Bombay.

.jpg)