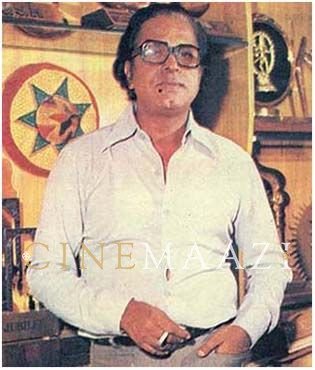

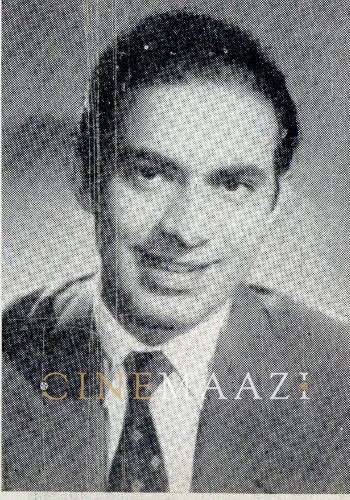

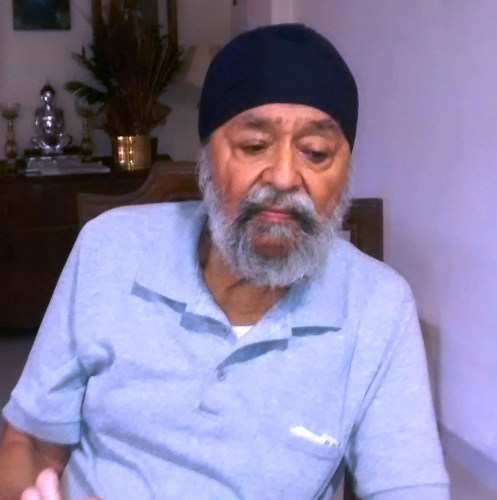

Karnail Singh and Sajjan Chowdhry

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

Well-known veteran foley artistes, Karnail Singh and Sajjan Chowdhry have worked in over 3000 films in the course of a collaboration of more than three decades creating sound effects or live effects for films. Initially referred to as sound effects or live effects, the function was named foley after Jack Foley, who pioneered various sound effect techniques for Western films. The work of Singh and Chowdhry has been relatively unsung though immensely valuable in enhancing the background sound of various scenes. Despite the developments in computer-generated sound effects, these expert foley artistes are not just relevant but much in demand as they deliver authentic and original sound effects which no software can deliver. Using a range of props, they have devised and recorded the everyday sounds heard in several popular films. Reproducing sounds such as footsteps, objects being placed, moved or broken, and also punches, crashes and explosions, they often employ surprising methods to achieve the desired effect. This can range from crushing a film reel to convey the rustling of leaves, twisting a plastic bottle to produce the eerie ambient sounds present in horror films, flapping a wallet to create the sound of a flight of pigeons, and dropping large particles of salt over an umbrella to mimic the sound of heavy rainfall. Their vast body of work includes films such as Sholay (1975), Parinda (1989), ChaalBaaz (1989), Dil (1990), Beta (1992), Hum Hai Rahi Pyar Ke (1993), 1942: A Love Story (1994), Andaz Apna Apna (1994), Naajayaz (1995), Maachis (1996), Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), Baadshah (1999), Josh (2000), Fiza (2000), Gadar: Ek Prem Katha (2001), Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), Company (2002), Devdas (2002), Bhoot (2003), Munna Bhai MBBS (2003), Dhoom (2004), Jodhaa Akbar (2008), Ghajini (2008), 3 Idiots (2009), Udaan (2010), Aisha (2010), Enthiran (2010), Tanu Weds Manu (2011), Don 2 (2011), Vicky Donor (2012), Gangs of Wasseypur (2012), English Vinglish (2012), Special 26 (2013), Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013), Mary Kom (2014), PK (2014), Badlapur (2015), Udta Punjab (2016), MS Dhoni: The Untold Story (2016), Padmaavat (2018), Sanju (2018), Andhadhun (2018), Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019), Super 30 (2019), Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan (2020), and Brahmastra Part One: Shiva (2022). Singh and Chowdhry operate together under the umbrella of Aradhna Sound Service. Recognition came to the duo with two consecutive nominations for the Golden Reel Award instituted by the Motion Picture Sound Editors USA for the films Roar-Tigers of Sunderbans (2014) and India’s Daughter (2015; winner). The awards are regarded as just a notch below the Oscars.

Harking back to their journey as collaborators, Sajjan Chowdhry had travelled from Moradabad, a small town in Western UP, to Bombay. Starting his career in 1982 as a dubbing recordist, he joined as a trainee under the tutelage of Karnail Singh at Sea Rock Sound Studio. After the studio shut as a result of the bomb blast that rocked Sea Rock in 1993, Singh joined Natraj Studio, while Chowdhry and Rajendra joined Dev Anand’s KetNav. More than a decade later, the trio joined Aradhna Sound Sevice. With several decades of experience, Chowdhry and Singh are believed to be the best in their field. They have worked with a range of filmmakers, from avant-garde geniuses such as Mani Kaul to commercial crafters such as Rajkumar Hirani, Karan Johar, Ramgopal Varma and Sanjay Leela Bhansali, as well as noted sound designers like Biswadeep Chatterjee, and Resul Pookutty.

Alluding to foley as a thinking man’s job translated into action, the duo explains that they “feel the film, and feel the character”. Their highly detailed work even includes producing walking sounds that match the personality on screen. For instance, veterans like Amitabh Bachchan and Naseeruddin Shah have distinct military walks, while the young actors of today have relatively casual gaits, for which they according produce the desired sound.

According to Singh, today, films are made with sync sound but that largely captures the dialogue. Once the dialogue is cleaned by the sound engineer, the rest fades. They come in to give the feel of a location.

In contrast to current times, when productions are more helpful in enabling foley artistes to achieve the desired sound by providing actual props, the veteran foley artiste duo has employed ingenious ways to produce the desired effects despite the lack of essential props. For Parinda, the Vidhu Vinod Chopra-directed crime drama, they had to produce the sound of footsteps on a tin roof, a body falling on the roof, and also the clanging sound of a dropped sword. To produce these effects, they borrowed the metal sheet that had served as a makeshift bridge over a gutter between Natraj Studios and Seth Studios.

Again, in Parinda, in order to match the grim scene in which Anil Kapoor’s and Madhuri Dixit’s characters are murdered, they created wire-taut tension using just the sound of a creaking chair.

Chowdhry and Singh consider Bajirao Mastani their most challenging yet fulfilling project. They had sourced a danda-patta (gauntlet sword) to achieve the precise swishing sound of a sword cutting through air; however, eventually the weapon was not used in the studio as it was deemed too dangerous.

In the blockbuster Sholay, before the start of the song Jab tak hai jaan, Hema Malini was picturised dancing on shards of glass – those pieces were actually plastic. When the 3D version of film was released in 2014, the duo smashed glass bottles on the studio floor on which they moved their hands, encased in leather gloves, in rhythm with the actor’s dance.

Other surprising sounds effects include Chowdhry kissing his own wrist to match the kissing scenes between Arjun Kapoor and Kareena Kapoor in Ki & Ka (2016), and the eating of a plate of mutton to produce the sound of a cat nibbling on a corpse in a scene in the Vikram Bhatt horror film 1920 (2008).

The duo works together in seamless understanding. While Chowdhry is partial to recreating the sounds of punches and clothes tearing, Singh prefers the more nuanced sounds of the ruffling of garments and the clinking of cutlery.

The duo’s workshop contains a wide range of objects from different kinds of shoes, doors, glasses, plates, nails, hand globes, dresses, bangles and more that are used to create the desired sound. Their ‘secret weapons’ include wooden logs to break open doors or create crashes and thuds; a plastic bag that can be crumpled to mimic the sound of fire crackling; and empty coconut shells worn as gloves to produce the sound of a horse’s gallop.

A good chunk of their work often gets drowned out by the background score and also escapes the attention of the audience. However, some filmmakers ensure the foley sounds are audible alongside the background score, as they help establish the mood.

Singh and Chowdhry believe that as foley artistes they do not get the kind of recognition they deserve as their work cannot be visually seen on screen, but only experienced. The role of sound as performance and its ability to change a visual has yet to be fully acknowledged and appreciated.

References

https://desireflections.blogspot.com/2018/01/sajjan-chowdhary-transformation-of.html

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm1180030/fullcredits

https://www.facebook.com/Aradhanafoley/photos/a.510745259292558/510776285956122/?type=3

https://desireflections.blogspot.com/2018/01/sajjan-chowdhary-transformation-of.html

.jpg)